Back to Polemix

On Paper

Response given at

the conference ‘On Paper’, Beveridge Hall, Senate House, 30 April 2010

On a couple of

occasions lately I have had the chance to think about paper and also the end of

paper. Of course paper is a manifold thing.

I happen to have

been reading ‘In Praise of Shadows’ by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, a treatise on Japanese aesthetics in the

everyday written in 1933. It is a bewailing of the end of certain practices,

flushed out by Western style – the purging of shadows by the new electric

lights, the replacement of wooden and foliage toilets by shiny porcelain, the

metal nib replacing the brush, blue ink replacing black. Paper features much.

It was lived with. In the traditional Japanese house there was a shōji (障子), a window-wall of translucent

paper over a gridded frame of wood or bamboo. It was this – so unlike

glass windows or brick walls – that produced the shadows and the soft

light of living.

Tanizaki also speaks of paper for writing and

drawing –on – as an author it is of course a concern to him. He

writes:

I

understand paper was invented by the Chinese; but Western paper is to us no more than

something to be used, while the texture of Chinese paper and Japanese paper

gives us a certain feeling of warmth,

of calm and repose. Even the same

white cloud might as well be one color for Western paper and another for our

own. Western paper turns away the light, while our paper seems to draw it in,

to envelop it gently, like the soft surface of a first snowfall. It gives off

no sharp noise when it is crumpled or folded, it is quiet and pliant to the touch as the

leaf of a tree.

Indeed Tanizaki

goes so far as to say that from the adoption of Western writing implements, ink

and paper, gathers the clamour to

replace Japanese characters with Roman letters. Were this not so:

our thought and our

literature might not be imitating the West as they are, but might have pushed

forward into new regions quite on their own. An insignificant little piece of

writing equipment, when one thinks of it, has had a vast, almost boundless,

influence on our culture.

I mention this only

because it struck me that paper is not one thing but many. And because if there

is a sense of loss or reinvention as we move into the paperless era –

which as we know has not yet proven to be such – then this text too

speaks of loss, as a certain sense of paper is replaced and along with it come

all sorts of implications. This aesthete’s sense of the world is echoed for me

in Walter Benjamin’s relationship to the political-aesthetic shaping of the

everyday, including in relation to paper.

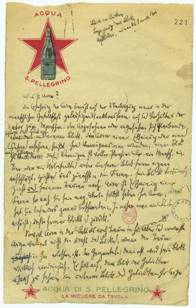

I remember being struck by a

passage in a letter from January 1934 to Gretel Karplus – when Benjamin

was at his poorest, barely surviving in exile in Paris, and keeping warm by day

in the Bibliotheque nationale. He writes:

Now I have a small

and bizarre request regarding the arcades papers. Since the first setting up of

the numerous sheets on which the notes are to reside, I have always used one

and the same type of paper, namely a normal letter pad of white MK [Max Krause]

paper. Now my supplies of this are exhausted and I would very much like to

preserve the external uniformity of this bulky and thorough manuscript. Would

it be possible for you to arrange for one of those pads to be sent to me?[1]

The paper had to

remain the same. Odd in a sense – for this was a man who had got used to

working on scraps – an aesthetic of refuse. The scrap was a way of

managing and delivering information. Benjamin repeatedly treated the

composition of his work as a form of collage: he wrote out his thoughts and

also copied out the thoughts of other authors, then cut them out, stuck them on

new sheets of paper and arranged them anew. He would dash down thoughts on any

scrap he could find.

He carried

notebooks with him to record sudden flashes. All his scraps of paper, sketches

of essays jotted on the back of library book return reminders, wind roses and

co-ordinate planes that plotted ideas in relation to each other were archived.

Even the most ephemeral of texts, objects, images found a place in his archive.

The archive had its external posts. Benjamin’s notebooks crammed with tiny

writing were deposited with friends and could be recalled by him at any time.

Benjamin’s notebooks, unlike his other scraps, testified to a fine taste, finer

than Artaud’s – no school exercise book for him, but rather chamois

leather and vellum. Other people broght them for him. This was not a part of

the aesthetics of necessity. This was an archive that was organised in various

modes, including by written format (‘printed’, ‘only in handwriting’,

‘typewritten’). And Benjamin worked on a book that was never to be, a scrapped

book that remains a scrapbook – The Arcades Project, a work composed almost entirely of quotations and devised

such that the material within it remains mobile, its elements can be shifted at

will. His thoughts, the thoughts of others, thoughts on prostitutes or

bourgeois private gentlemen, advertising or fine art, all this is of equal value,

for knowledge that is organised in slips and scraps knows no hierarchy.

Hierarchies in

Benjamin’s view also collapse in relation to mass reproduction. There is a

tension between the inviting tactility of the usually artworld, usually

semi-restricted commodity and the desire to keep it pristine, as investment

object. But, another type of book can surface – the children’s book,

books that insist on play, on tugging, pulling, unfolding, teasing, gaming an

even sometimes, as in annuals, writing, drawing or colouring in. Benjamin

enjoyed and encouraged child’s graffiti on books and cuttings out, even though

he was a collector of same.

I want to stay with

Benjamin for a few moments more. Yes, he was a fetishist of paper – and

of certain pens and inks. He wrote about handwriting on various occasions

– was a trained graphologist too. But he also yielded, without nostalgia,

to the pressures of modernity, commandeering the typewriter for his letter

writing, controversially, for it offended his friend Scholem to receive such a

missive. He had thoughts about

what the typewriter was and might become and how it might change everything,

once we had changed it. He writes about the possibility of new modes of

notating thought and suggests that the mechanical transposition of the

typewriter or other future machines will be chosen over handwriting only once

flexibility in typeface choice is available. Such flexibility is necessity

because only then can all the nuances of thought and of expression be captured.

One single standardising typeface could not provide this, he argues. Once

versatility is achieved the writer might happily compose directly on the

machine, rather than with pen in hand - this would of course

affect the resultant composition, and books would be composed according to the

capabilities of the machine, much as photographs eventually found their own

aesthetic rather than imitating painting’s one. Benjamin writes:

The typewriter will alienate the hand of the literary

writer from the pen only when the precision of typographic forms has directly

entered the conception of his books. One might suspect that new systems with

more variable typefaces would then be needed. They will replace the pliancy of

the hand with the innervation of the commanding fingers.[2]

Without this

flexibility in mechanical systems of writing, what is being lost, according to

Benjamin? The pliancy of the hand in writing allows for the recording of

meaning in the form of a trace, which possesses a shape, a size, an amount of

pen pressure. The standard characters of the typewriter can barely imitate

this. Benjamin imagines and hopes for a type of mechanical reproduction that

could incorporate these other aspects, and so allow extra-layers of meaning to

be drawn from the content of words and the ways they are drawn. He imagines a

future machine, suggested by the present one, but far exceeding its capacities.

Only with this would this writing be adequate for purposes of expression. With

his fantastic machine, the energetic dance of the fingers jabbing away at a

keyboard of variable typefaces sensitive to hues, tones and shades of meaning

would type at high speed but relinquish none of the extra-linguistic meaning

intimate to handwritten characters. These extra-linguistic aspects amounted to

a type of scriptural unconscious and they were what made graphology possible.

Graphology was a technique that fascinated Benjamin and in 1930 he complained

that the academy had still not accepted this scientific method and had

appointed to date no chairs for the interpretation of handwriting.[3]

He contended that: ‘Graphology has taught us to recognize in handwriting images

that the unconscious of the writer conceals in it.’[4]

And this is because it takes place in a cubic space of the paper, depths

discovered in the surface. All handwriting is, for Benjamin, like the writing that takes

place on Freud’s ‘mystic writing pad’, the children’s writing tablet

that was, for Freud, an analogue of consciousness with its capacity to forget

temporarily, but always potentially recall or be assailed by any memory trace

at any moment.[5] Freud noted

how the mystic writing pad with its wax, translucent paper, celluloid and

pointed stylus allowed both erasure and retention, for words, images can be

written and then erased by an easy movement of the hand, while permanent traces

of all the etchings that have been made on it are retained beneath. For

Benjamin, the graphologist, the scratches of the surface of articulation, the

surface of writing, can likewise be probed in order to reveal a deeper

significance. Quite literally, for in 1928 Benjamin makes that claim that any

scrap of writing, any few handwritten words, might be what he calls a free

ticket to the great theatre of the world, for it is, he says, a microcosm of

the ‘entire nature and existence of mankind’.[6]

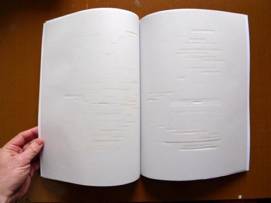

Interestingly, just as the Artaud’s notebook facsimiles have appeared, so too

have reproductions from Benjamin’s archive in book form. We can read his

handwriting and doodles, his graphic layouts of drafts of essays and so on.

Scraps, bits and

bobs, cutting and cuttings. Here were are with a sensibility that has been

prominent on the day. I was struck in panel 3, Marking the Surface, by each

paper’s more or less explicit dealing with chance through collage, cutting,

disjuncture. Heather spoke of the fear of arbitrary sign systems on the part of

the sighted. But they came because like the chance encounter of an umbrella and

a sewing machine on an operating table the moment was right. This hammered home

in Patrizia’s comments on photography and its chance illuminations, its

arbitrary capturings of frozen instants – expressed by Benjamin as its

access to an ‘optical unconscious’. Henderson spoke of the chance

configurations of books curated in Sinclair’s passageway stall and the thrill

of chance findings, the great tosher’s dream fulfilled. And it was al initiated

by Luisa’s sense of the peculiar disjuncture on Blake’s collaged page in the

intermingling of proto-mass and unique papers and modes – as also in

Adam’s commonplace book. I wondered after it all if the page seen from this

aspect of its discordant papers, surfaces, depths and volumes, scraps and

fragments, was Blake or john Gibson made again for as a contradictory

configuration, a modernist avant la letter, whose homogenization in the web

triggers ‘that infinite that lay hid’. Our researches are never exhaustive. The

object that has passed through time bears traces or maybe punctures, woundings

– to bring up the paper/skin analogy – that can open and reopen and

yield new contents, new meanings on that basis of what Tony called a ‘material

textuality’ that includes the physical features of the text.

Handwriting.

Typewriting. Books. Pamphlets. Ends and beginnings. Scraps. Stuff scrapped.

Books scrapped by circumstance or design. Scrapings. All of these forms needs their readers too. In One Way

Street from the 1920s., Benjamin talks of getting his hands on a long desired

book. He gives himself up to the ‘soft drift of the text’, which ‘surrounded’

him as secretly, densely, and unceasingly as snow’. To the reading child, ‘the

hero’s adventures can still be read in the swirling letters like figures and

messages in drifting snowflakes’. The reading child’s breath is part of the air

of the events narrated. He mingles with the characters, and ‘when he gets up,

he is covered over and over by the snow of his reading’. That drifting – here a snowy

thing – came up in relation to the digital, the digital derive, adrift in

the text of the web – a mode of reading. Benjamin perhaps got to this too

– in his notion of the flurry of letters released into the cityscape.

I think of his

swirling words, flotsam of a dreamy Romanticism, as re-articulated in more

modernist guise in Benjamin’s thoughts on literacy in the modern cityscape. As

he puts it, in One Way Street, newly

expelled from what he calls the bed-like sheets of a book, ‘a refuge in which

script could lead an autonomous existence’[7],

words flicker across the night skyline, glimmering their neon messages above

shops, or they stand upright on posters, newspapers or cinema screens. He notes:

If centuries ago it

began gradually to lie down, passing from the upright inscription to the

manuscript resting on sloping desks before finally taking itself to bed in the

printed book, it now begins just as slowly to rise again from the ground. The

newspaper is read more in the vertical than in the horizontal plane, while film

and advertisement force the printed word entirely into the dictatorial

perpendicular.

These vertical and

sometimes moving scripts make the fixed and regular print in the book seem

archaicly still. The urban dweller must be able to read such a cityscape - its

signs, its words, its images, a ‘blizzard of changing, colourful, conflicting

letters’. Script, he notes, ‘is pitilessly dragged out into the street by

advertisements and subjected to the brutal heteronomies of economic chaos’. And

it resonates with developments in art, where, since Mallarmé, the graphic

nature of script is incorporated.

Mallarmé predicted

the future, Benjamin claims, incorporating in his 1897 poem ‘Un coup de dés’

all of ‘the graphic tensions of the advertisement’. Apollinaire took this

further in his Calligrammes in the

second decade of the twentieth century with his ‘ideographic logic’ of spatial

rather than narrative disposition.[8]

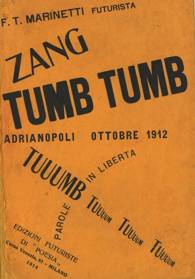

And the Futurists

clambered on board too, with Marinetti insisting on typographical revolutions,

to express the disruption of syntax, metre, punctuation in pursuit of ‘lyrical

intoxication’ in his efforts at abrupt instantaneous telegraphic

communications. Words rise up.

I think today often

of this swirling, chaotic writing, of writing screaming from billboards, moving

vehicles, LED screens, as it has for so long – demanding and never

finding really adequate enough attention. It may be that our reading, day to

day, in the cityscape, is more like the traipse through the blizzard of words

that jostle for our attention, while we absorb them more dreamily,

inattentively. This might be the true struggle that is going on on the streets.

But they seem currently to have the upper hand. If Benjamin saw them mobilise

into uprightness, now they swarm, chasing us, catching up with us wherever we

are in those little handheld gadgets that people carry. Beeping, squawking,

demanding attention. A flurry of messages keeping us on message – on line

– on a line, hooked, lined and sunk. Our attention is commanded.

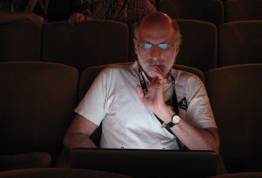

And I am captivated

by an image that I have yet to decode. Walking into the British Library or any

other library, even in cafes, all over the place, the reader-writers sit in

ranks, gazing at an upright screen, its greeny-blue illumination lighting up

their face, in the shadowy realms that the post EU light bulbs engender.

A certain return to

Tanizaki’s shadows? Or each human for his or herself a glaucous aquatic gleam. The shadows will be chased out again

soon though. Apparently this sight will no longer be with us in 5 years, as

electronic ink – if the sort in Kindle Machines – needs no

backlight and will become the preferred mode of display.

We have heard much

today about disappearances. Zara spoke of the heightened consciousness of

materiality and how the new forms reveal to us what we never knew about the old

ones as they are threatened with extinction. Known to themselves, perhaps for

the first time, they rally, excelling in what they alone can do. It reminds me

of the thought that it was only once photography had perfected verisimilitude

in the image, albeit in black and white, painting stressed impression and

colour. Medium-specificity is something that goes on reinventing itself.

We are all readers

and researchers. That is important. Our particular investments as researchers

are crucial. Other questions arise for those who are satisfied with their

e-readers. Laurel’s talk made me ponder the etymologies of browsing and

brwosers, of searching and researching. Re-searching implies that scholar look

again and again, or find something they lost before. If we find that which was

sought before, this suggests something of that idea of reinvention: that for

us, the digital interface refinds, or looks again after print matter, the lost

thing. We come to know it anew. But what we come to know conclusively is that

it has bulk, weight, presence – enough to driver arbiters of space and

storage to distraction. Roland Barthes said of the historian Jules Michelet

that he sat in the archive and ingested history, the dust floating up into his

lungs from those old books, their leather covers, their crumbly pages, he

– as we say – devoured, seeking out the histories of France. What

is our food for thought in front of screens? Michelet’s dust transformed for me

into Iain Sinclair’s dirt now archived inside his pamphlets at the Harry

Ransome Center in Austin, Texas. Not the dust of paper and leather but a trace

of labour. It is the dirt that tumbled from his fingers as he wrote in those

now archived notebooks in snatched moments while working as a gardener and

labourer. I wonder if the trace of

labour gets erased or obscured in the digital age. If it becomes imperceptible

because of networks and mechanisms that tend towards invisibility. The book is

an artefact. We know that system. We know the weight and value of its paper,

its print. We know its publishers. We know its bringing into being through chains

of labour. What do we know of labour on the web or with the e-reader. Text

comes to us as data, run through various display mechanisms, whose own status

as artefacts easily becomes invisible. All that labour of programmers and

server maintainers, of data inputers appears and does not appear. Property and

labour are in strange relations on the web – witness pirating, pirate

facsimiles on Aaaargh and the rest. Or labour is given freely in Web 2.0 in the

blogosphere, where data is given up endlessly without remuneration. Labour is

the same in cyberland, but different too.

Back to Polemix