Esther Leslie und Ben Watson

Delivered at the Hochschule für Graphik und Buchkunst, Leipzig, 4 June

2002

The value of materialism as a philosophical orientation for approaching artistic issues has been undervalued for too long. Like Lenin's Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (1908), Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont's Intellectual Impostures (1998) has been hushed up, as if the mention of scientific fact and a material universe independent of human consciousness is dangerous, an invitation for the philistines to destroy the precious flowers of cultural existence.

Nevertheless, the designation of certain cultural products as holy has always resulted in iconoclastic responses. A materialist theory of culture needs to be able to recognise the way in which social hierarchy damages the psyche, and include destructive tendencies in its dialectic. Without recognition of this animosity towards received culture, culture because something external to the self, an oppressive set of maxims and rules. Hans Richter, both a participant and annalist of dada, named its dialectic 'art and anti-art'. When, at the height of the punk furore, the manager of the Sex Pistols Malcolm McLaren was accused of provoking violence and destruction at punk gigs, he replied 'you've got to be able to destroy to create'. It is not for nothing that The Beano, the most widely read children's comic of the 1970s, expresses a continual animosity to civilisation in favour of jokes, chaos and transformation.

Rather than targeting a subordinate race or nation as the object of destruction, dada targeted the educated person's own culture and refinement, deriding the pretensions of culture and allowing the recovery of a universal humanity, the laughing body. It is our contention that a new revolutionary marxism, uncontaminated by the compromises of Stalin's idea of 'socialism in one country', needs to recover this egalitarian aspect of dada, which is also to be discovered in the subversive and pornographic aspects of the work of James Joyce.

One of the fears expressed about a materialist theory of culture is that it destroys joy and magic, reducing everything to the hard facts of economics and history. It is just the other way about. By elevating the imagination to a separate sphere, cultural idealism actually quarantines it, and prevents it having a productive relationship to scientific and practical endeavour. If truth is 'objective rather than plausible', as Adorno put it [Negative Dialectics, p. 41], then the most astonishing thing is not the special leisure gardens of the soul set aside by an administered society, but the moment when actuality breaks in and jolts conceptual systems. As the surrealists discovered, one of the most extraordinary aspects of the materialist approach is 'coincidence' - or what looks like coincidence to those positivists who believe in a Cartesian separation between the realms of soul and body, thought and the universe.

In 2001, Marco Maurizi wrote a paper called 'Sophopraxis: An Enquiry Concerning Inhuman Understanding, or The Joy of "Zounds!"'. Pursuing a dada materialism which referenced Hegel, Marx, Adorno and Frank Zappa, Maurizi concluded by examining Tristram Shandy, a work published in between 1760 and 1767 by the Irish-born writer Laurence Sterne. Maurizi's argument, perhaps out of reaction to having just completed an academic thesis on Theodor Adorno, was driven by the pleasure principle, deliberately leaping over historical periods and making 'absurd' connections. Tristram Shandy is a famous humorous novel which perpetually mocks the idea of stable systems of representation and the 'paradigms' of space and time which Kant declared were fundamental to human perception. Like James Joyce, Sterne uses sexual materialism to mock both bourgeois morality and bourgeois rationalism, introducing body functions in the most unlikely places. Tristram Shandy begins his biography - logically enough - with his own conception. His parents' sexual congress is interrupted when his mother asks his father if he has remembered to wind up the clock: the protest against mechanical reason could not be more graphic. The passage examined by Maurizi contains a discussion about the meaning of 'Zounds!', an English swear word said to be derived from 'God's wounds', referring to the crucifixion of Christ. Semantic and grammatical structures are found to be inadequate to comprehending the expressive and involuntary expressions of the human body. Maurizi concludes by saying that Sterne's treatment of 'Zounds!' could become the foundation of a Dadaist Science founded upon the idea of surprise.

Maurizi started with Kant and Hegel, went on to Gramsci and Adorno, and appears to have ended in absurdity. It is easy to imagine the earnest political revolutionary declaring that Maurizi has left the bounds of Marxism and descended into ludic postmodernism, that cultural playpen where everything is allowed because nothing really matters. However, although Maurizi is incredibly well read, he does not - fortunately for his own morale and prospects for an interesting future life - know everything. What he did not know is that the young Marx read and enjoyed Tristram Shandy. In the late 1830s, he even wrote an emulation of it named Scorpion and Felix. The biting satire of classics like the Eighteenth Brumaire and Das Kapital would not have been possible without Sterne's literary example.

In chapter 37 of Scorpio and Felix, Marx satirises David Hume, whose radical empiricism caused him to question the reliability of any knowledge, thus refuting the progressive politics of the Enlightenment in its own terms:

David Hume maintained that this chapter was the locus communis of the preceding, and indeed maintained so before I had written it. His proof was as follows: since this chapter exists, the earlier chapter does not exist, but this chapter has ousted the earlier, from which it sprang, though not through the operation of cause and effect, for this he questioned. Yet every giant, presupposes a dwarf, every genius a hidebound philistine, and every storm at sea - mud. As soon as the first disappear, the latter replace them, sitting down at the table and sprawling arrogantly with their long legs.

The first are too great for this world, so they are thrown out. But the latter strike root in it and remain, as one may see from the facts, for champagne leaves a lingering aftertaste which is repulsive. Caesar the hero leaves behind him the play-acting Octavianus, Emperor Napoleon the bourgeois Louis Philippe, the philosopher Kant the carpet-knight Krug, the poet Schiller the Hofrat raupach, Leibniz's heaven Wolf's schoolroom, the dog Boniface this chapter.

Thus the bases are precipitated, while the spirit evaporates. [Karl Marx/Friedrich Engels, translated Alick West, Collected Works, Vol. 1, London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1975, chapter 37, p. 628].

Marx's biographer Francis Wheen is correct to see in this passage an anticipation of the famous opening lines of the Eighteenth Brumaire, which mocked Napoleon III as a farcical repetition of Napoleon Bonaparte. Sterne's debunking satire, which contrasts shabby reality with grand ideals, made a permanent impression on Marx. This contrast is contained in the marxist insult 'epigone', and describes the degradation of the presentday politicians and cultural figures in comparison to the illustrious history they appeal to for legitimacy. Marx's idea of using the past, not as justification for a miserable present, but as its judge and executioner is contained in both Trotsky's theory of Permanent Revolution and in Benjamin's idea of saving culture from the conformism which threatens to overcome it. This view of history as revenge on the present separates marxists from anarchists and postmodernists, whose only hope lies in an undetermined, brandnew future.

Marx's conclusion - 'thus the bases are precipitated, while the spirit evaporates' - accuses the current ruling class of being the dregs, thus applying to them the insult they direct at the proletariat. Marx's satire concludes with a dog named Boniface (apparently the 'one and the same as Saint Boniface, the apostle of Germany', citing in proof his Epistles no. 105, where he describes himself as a barking dog) being given an enema of oil, slat, bran, honey and clyster.

'Poor Boniface! You are constipated

with your holy thoughts and reflections, since you can no longer relieve yourself

in speech and writing!'

'O admirable victim of profundity! O pious constipation!' [same chapter 48, p. 632]

The equation between literary production and the moving of the bowels was also one made by James Joyce. It is not simply scatological satire of the high and mighty, but insistence on the human agency in literary production, refusal to allow the text's productive source in the writer's physical and social being to be obscured by transcendental concepts. Marx's satire on David Hume is based his own productivity as a thinker and writer: he attacks Hume's skepticism by accusing it of an a priori certainty that what he is writing at the minute will only be the lifeless residue of previous ideas.

According to Marx, with the rationalism of the new bourgeois science, that of Bacon and Hobbes,

knowledge based upon the senses loses its poetic blossom, it passes into the

abstract experience of the geometrician. Physical motion is sacrificed to mechanical

or mathematical motion; geometry is proclaimed as the queen of sciences. Materialism

takes to misanthropy. [Marx/Engels, The Holy Family, or Critqiue of Critical

Criticism, 1844, translated Richard Dixon and Clemens Dutt, Moscow: Progress,

1975, p. 151.]

The idea of knowledge as a product of human activity, as practice, was only preserved by the idealist philosophers. Marx set himself the task of bringing these two sides together and creating a humanist materialism. Currently, it is post-dada Modern Art which insists on the active authorship of concepts, but only if it accepts a role as the provider of purchasable ornaments for the super-wealthy. To bring the truth content of modern art together with that of social science - Adorno's project - it is no use simply defending the role of art in contemporary society. The only explanation for the 'coincidences' surrounding the independent use of Tristram Shandy by Marx and Marco - as well as the parallel scatology of Marx and Joyce, and the canine continuity between Marx and Zappa - is a materialist account of culture. Genuine cultural theory is not a religion, passed on like a precious heirloom from one thinker to another, but an indexical response to actualities of life and society. The things which astonish us as 'coincidences' are not actually coincidences, any more than the fact that all poets speak of love and the moon. The problem is that society has become so transfigured by culture, so over-cultivated, that revelations about the material body - sexual, scatological, canine - seem like exceptions to the norm. In the late 40s, the painter Asger Jorn declared that the 'acid test' of anyone's philosophy was whether it could accept that the human is an animal. Denial of this fact was the root cause of all social oppression, from the Ancient Greek subordination of women all the way through to Hollywood's sexism. The defensiveness when faced with Sokal's critique shows that the American left has succumbed to liberal and transcendental notions of the function of culture: it has become a religion to be protected rather than a science to be tested.

The image of culture as a house of cards which any breath of disrespect might topple is not based on an understanding of the role of culture in modern society, but from tendentious pleadings by professional intellectuals and academics. This 'defence of culture' is a metaphysical reflection of class society, and its hierarchical distinctions between high and low, spirit and matter, culture and economics, noble consumption and base production. Karl Marx pointed out on the first page of Das Kapital that 'the capitalist system of production does not care whether the human needs that it satisfies stem from the stomach (Magen) or phantasy (Phantasie)'.. A robust cultural theory needs to be able to deal with this fact. Progressive cultural criticism is not about selecting the best items for consumption, but about creating conditions for the self-production of culture. By elevating past productions above contemporary possibility, the neo-classicist vaunts property over labour and saps the confidence of the producers. It was not for nothing that Theodor Adorno wrote criticism of contemporary composers, and could never bring himself to publish his numerous jottings about Beethoven. Even praising Beethoven's music as revolutionary could only be used as an excuse for cultural inertia.

If commodity production makes no distinction between needs springing from bodily appetites (Magen) and social imagination (Phantasie), it is because their undialectical separation is a metaphysical illusion, a residue of the Christian opposition between body and mind. Marx said that 'the criticism of religion is the perquisite of all criticism' ['A Contribution To The Critique Of Hegel's Philosophy Of Right. Introduction', 1844, Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, translated Rodney Livingstone and Gregor Benton, Early Writings, London: Penguin, 1975, p. 243]. There is no point in developing 'marxist' theories of culture if this fundamental position on the christian denigration of the body is ignored. In order to develop the 'spiritual sphere' as a social and political power, with its churches and monasteries and land, Christianity adopted the platonic argument that truth is eternal and abstract, while the actual things of the world are temporary and imperfect. Those who questioned this logic - Giordano Bruno for example - were burned at the stake. When Sokal is denounced because he shows that Jacques Lacan does not understand topology or that Julia Kristeva abuses mathematics, one feels a similar revulsion against heresy: 'defend the stipend at all costs!'.

One argument against Sokal is that, despite his claim to be on the left, and his record as a lecturer at the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua under the Sandinistas, his crude scientific positivism gives the right an opportunity to attack the left. All cultural work is in danger if we admit that poststructuralist and postmodernist philosophy is idealist and unconvincing. This shows a lack of confidence in the possibilities of a genuine materialism, one predicated upon the marxist idea of the emancipation of the working class, rather than upon creating academic spaces for deluded speculation.

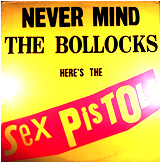

In the late 70s, the argument in England about Punk Rock was a graphic example of the difference between idealists, who define what people are by their choices in consumption, and materialists, for whom the essence of mankind's species-being is productive labour. The Sex Pistols deliberately produced music that was violent, nihilist and politically unsafe. It was not possible to approach except in a productive manner. In 1977, the listener had either to refuse the music, or become a punk in active opposition to humdrum existence. There was no possibility of using the music like Tubular Bells, as an ornamental addition to a regular life-style. Some elements of the left - including the Workers Revolutionary Party - denounced Punk as fascist, and would have nothing to do with it. In the Socialist Workers Party, we decided to split punk apart over the issue of racism, forcing its adherents to choose between nihilism against people and nihilism against property relations and immigration controls. Rock Against Racism was possible because, as marxists, we did not consider political truth to reside in transcendental concepts - such as love, peace and tolerance - but in the self-activity of bands and fans. The appetite for punk records and gigs was an objective social fact which the left had to relate to, not some 'commodity fetish' which the left could loftily ignore. Since punk served adolescent sexual needs as well as the need for social expression and adventure, there was no distinguishing between Magen and Phantasie.

A century before Punk emerged as latest rebel youth movement, the word itself meant something else: it meant something worthless, foolish, rubbish, empty talk, nonsense: such that Carlyle could speak of 'phosphorescent punk and nothingness' However when it came to future dreams for colour schemes punk preferred fluorescence's immediate shock of the intensified glow to phosphorescence's postponed illumination of its self in the darkness

Fluorescence

holds nothing back for later - like punk, its mode is the mode of anti-interiority,

denial of romantic self, a cheap trick, a cheap trip without innerness, an upfront,

slap in the face of public taste.

Fluorescence

holds nothing back for later - like punk, its mode is the mode of anti-interiority,

denial of romantic self, a cheap trick, a cheap trip without innerness, an upfront,

slap in the face of public taste.

One way of blowing apart the dead inevitability of history written with hindsight - its placid affirmation of the status quo - is Walter Benjamin's method of seizing on a significant detail. This was actually a development of Benjamin's reading of Marx's Capital. Benjamin's hallucinogenic focus on a single detail jolts a moment from its place in a preordained sequence of events, and lets in the multivalent possibility inherent in human action. As Hegel said in the smaller Logic, para. 143, 'Viewed as an identity in general, Actuality is first of all Possibility.' [G.W.F. Hegel, Logic, 1817/1827, translated William Wallace, 1873, Oxford: OUP, 1975, p. 202]. The Punk story told in terms of chart placements and fame immediately puts Punk back in the pop logic it was a protest against, whereas reveries about shopping schemes, council tenancies, bondage and Day-Glo can take us back into the first moments of Punk's immediacy, its shock and exhilaration - the heretical idea of living historically instead of at the behest of the needs of capital accumulation. No past, no future, no capital, no mortgage payments.

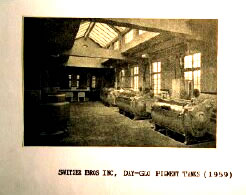

Day-Glo was the colour of choice for punk. Day-Glo had been around for some

time when punk appropriated it. In the 1930s, after one of them received a bonk

on the head and a spell of recuperative treatment under ultra-violet light,

Bob and Joe Switzer, eager young experimenters, were mucking around with dyes

and resins to make colours that were brighter than normal and glowed under u.v.

light. They used these new fluorescent colours in their hokey little magic shows.

The colours were eye-catching, because they shone brighter than other colours.

It was as if a new part of the spectrum had been discovered. Day-Glo colours

are composed of fluorescent materials. Colour arises in ordinary objects through

selective absorption. Ordinary paint absorbs some of the spectrum from white

light and reflects the rest. Red paint absorbs blue and yellow, resulting in

the scattering back of only red. Day-Glo paints do not simply scatter back light

from the visible part of the spectrum. They can also take shorter wavelengths

(usually ultraviolet) that are invisible to our eyes and they re-emit the energy

by converting it into photons of longer wavelength. Thus, ultraviolet light

goes in and its energy is converted into visible light emitted by the chemicals

in the paint, creating the bright fluorescent quality. Fluorescent materials

emit more red light for example, than ordinary red objects because they take

some of the ultraviolet light that is invisible to our eyes and emit it as visible

light. Day-Glo lets more be seen - it shines brighter. In 1936 the Switzer brothers

set up a firm in Cleveland.  War

came and the colours found military application in bright signal panels used

by the army, but peace put them back into civilian use on billboards, in safety

signage and promotional publicity, and soap powder boxes. Outside the military

context, Day-Glo was associated with vulgarity - the too obvious - the screamingly

evident.

War

came and the colours found military application in bright signal panels used

by the army, but peace put them back into civilian use on billboards, in safety

signage and promotional publicity, and soap powder boxes. Outside the military

context, Day-Glo was associated with vulgarity - the too obvious - the screamingly

evident.

In the 1950s the name Day-Glo was trademarked and in the late 1960s the company formally changed its name from Switzer Bros Inc to Day-Glo Colour Corp. In their names one can hear the poetry of science, industry and space exploration. The full trademarked pigment set comprises Neon Red, Rocket Red, Fire Orange, Blaze Orange, Arc Yellow, Saturn Yellow, Signal Green, Horizon Blue, Aurora Pink, Corona Magenta, Strong Corona Magenta, Strong Saturn Yellow. Day-Glo first infiltrated the American landscape as entertainment then as an alert to danger and later as commodity shriek. A fan of Ultraviolet light, who runs a website dedicated to its discussion, writes of a trip to Disneyland in the Summer of 1961. There he rode through psychedelic landscapes - such as the Alice in Wonderland ride - made of Day-Glo scenes extra-illuminated under u.v. light (see here). Day-Glo fluorescent paint was fairly easy to get hold of in the 1960s - it became a household word through Tom Wolfe's book on Ken Kesey and the Pranksters. It remained a bad taste product, acceptable only to commercial art, where Psychedelia found a use for it in posters and it found its way into film. In the entry on the word Day-Glo the OED quotes an article from the Listener, from 1968, which condemns the use of flashing Day-Glo colours as vulgar signal of an orgasm in a film by Jack Cardiff. The hippies used Day-Glo in their cultural artefacts, and even on their bodies, but theirs was an attempt to paint over the world in the colours of their hallucinogenic trips. Day-Glo was being taken into the student bedroom, the kids' blacklit den where individual mediation could hinge on the wonders of a perceptual trick that disappeared when normal electricity resumed.

It took

punk to fully assimilate Day-Glo without transforming it - that is vulgarity

and all - in fact because of its bargain-basement, eye-catching impudence. Jamie

Reid's cover for Never Mind the Bollocks modelled itself on a crude supermarket

display. This was consumer society staring itself in the face. Art, as ever,

was behind the times when Peter Halley began to use Day-Glo paints in his abstractions

in the 1980s. Punk had already camouflaged itself in the colours of the antagonist.

It took

punk to fully assimilate Day-Glo without transforming it - that is vulgarity

and all - in fact because of its bargain-basement, eye-catching impudence. Jamie

Reid's cover for Never Mind the Bollocks modelled itself on a crude supermarket

display. This was consumer society staring itself in the face. Art, as ever,

was behind the times when Peter Halley began to use Day-Glo paints in his abstractions

in the 1980s. Punk had already camouflaged itself in the colours of the antagonist.

In 1914, a member of the Rebel Art Centre, Wyndham Lewis launched a Vorticist magazine. Lewis' BLAST was supposed to be a celebration of the blast furnaces of the industrialized Midlands and North. Blast also suggests a hygienic gale from the North. The emblematic representation of the vortex on the first pages of Blast is a figuration of a storm-cone with the apex up: a signal used by coastguards to represent strong winds from the north.

Blast lends perhaps the visual and polemical aesthetic of the punk fanzines. Blast - with its glorious outrageously luridly pink cover and heavy anonymous blockish black typography and polemical rants - was just as shocking as the Sex Pistols Never Mind the Bollocks LP cover.

Designed in 1913, printed in 1914, Blast was designed to be a verbal expression that could be adequate to the 'stark radicalism of the visuals' that Lewis had been developing in the previous years. (Letter to Partisan Review, from Lewis, 1949, quoted in Richard Cork, Vorticism, I, p260.) The Pall Mall Gazette, describing the cover as the colour of 'chill flannelette pink' added that the colour 'recalls the catalogue of some East End draper, and its contents are of the shoddy sort that constitutes the East End draper's stock'.

Blast was written by self-styled 'Primitive Mercenaries' (p30), savage artists mingling in the 'enormous, jangling, journalistic fairy desert of modern life' (p33). In the glorious pink volume of Blast no.1 (of only 2) Ezra Pound presents some condensed Imagist poems on colour, artifice and chemicality.

Women Before a Shop

The gewgaws of false amber and false turquoise attract them,

Like to like nature. These agglutinous yellows.

Or again:

L'Art

Green arsenic smeared on an egg-white cloth,

Crushed strawberries! Come let us feast our eyes.

Or again:

The New Cake of Soap

Lo, how it gleams and glistens in the sun

Like the cheek of a Chesterton.

(all in Blast 1, 49)

These slogan poems cough up the major concerns of London Vorticism. In the first poem, consuming women are attracted to baubles, to the fakery of the commercial, a cheap trick to pull in the punters. They are attracted because they themselves no different, like eyes up like, each as artificial, false and hideous as the other. The second poem vituperates against art - in the modish French sense - as a mélange of poisonous tint and damaged nature on canvas. A feast for the eyes indeed bitterly evokes a deadly mess, of faked and ruined nature for those who know no better. The third poem parodies formal appreciation on the part of art lovers, by conceiving the aesthetic pleasures of bar of soap, cleanliness being its aim, just like the good clean English middle-class fun of G.K. Chesterton.

Pound had been requested to submit some 'nasty' poems to Blast. (see Cork, Vorticism).

The nastier the poems the better. But in what does their nastiness lie: in the

reference to the modern age's fakery and chemical inauthenticity. This acerbic

squeal found an echo 60 years later in Polystyrene's lyrical rejection of germ-free

adolescence and postwar plastics, engine of a new economy, in 'The Day the World

Turned Dayglo' - a chemical retort to the internalized hippy-trip of 'Lucy in

the Sky with Diamonds':

I clambered over mounds and mounds

Of polystyrene foam

Then fell into a swimming pool

Filled with fairy snow

And watched the world turn

Day-glo you know you know

The world turned day-glo you know

I wrenched the nylon curtains back

As far as they would go

Then peered through Perspex window panes

At the acrylic road

I drove my polypropylene car

On wheels of sponge

Then pulled into a Wimpy bar

To have a rubber bun

The x-rays were penetrating

Through the Latex breeze

Synthetic fibre see-thru leaves

Fell from the rayon trees

Polystyrene woke up in a world that was synthetic, just as the Vorticists had woken up in a world that was machinic. While Lewis publicly scorned Marinetti's 'Futurist gush over machines, aeroplanes, etc.' he was impressed by Marinetti's idea that humans are changed by living in cities with communications and transport at their disposal, and affirms a dada manifesto from 1918 which describes the dada sound poem as the sheer noise of urban existence, the screech of tram brakes, which wipe out traces of old-style individuality.

Punk's postwar version of Lewis' material desideratum forwarded not the machinic society but the plastic consumer society. Polystyrene again:

I know I'm artificial

But don't put the blame on me

I was reared with appliances

In a consumer society

...

My existence is illusive

The kind that is supported

By mechanical resources

...

I wanna be instamatic

I wanna be a frozen pea

I wanna be dehydrated

In a consumer society

Despite its lurid appearance, The cover of Never Mind the Bollocks was no cheap and easy, thrown-together item - it relied on modern painterly technologies. The printing process was difficult, because yellow is a 'notoriously bad colour to print as it shows up any impurities in the process very clearly. And, although the sleeve gives the impression of being simple, it uses a series of complex overlays. Fluorescent colours are hard to print as well, which doubled the difficulty.' (from The Incomplete Works of Jamie Reid p79). Reid also says: 'It was a feature of the finished sleeve that it deteriorated very quickly: if left out in the sunlight, the yellow and the pink faded, just leaving the black of the overlays.' (p79)

Evanescence and the mystique of fleeting intensity was arguably a core modernist theme, and Lewis had affirmed it already in a comment of his in the essay 'Futurism, Magic and Life' (Blast 1, p134) where he notes how the most perishable colours in painting (such as Veronese green, Prussian Blue, Alizarin Crimson) are the most brilliant. So that which burns brightest burns most briefly, and in true modernist fashion brilliance must be but fleeting, timely, not eternal, a coincidence of moment, viewer and object. Lewis proclaims of this: 'This is as it should be: we should hate other ages, and don't want to fetch £40,000 like a horse" - asserting the desire not to be commodified and not to become a part of the archive.

For Reid and the Sex Pistols, the painstaking work on the cover paid off, for the sleeve caused a fuss when it came out - mainly because it appeared to be the opposite of what it was - shoddy, cheap and nasty - and also because it had an anonymity as its theme - not only the cut out blockish - Blast-ish or newspaper headline lettering - but also the lack of 'stars' on the cover. No phosphorescent stars sending back their celebrity light to illuminate the gloom of adolescent fantasy - as The Clash, getting it so wrong would do with their first LP. The Sex Pistols, of course, did enstage themselves, not on the covers but elsewhere - however this self-display refused interiority, turning their selves into mannequins, for Westwood's clothes, McLaren's game.

The Day-Glo coloured vinyl punk record is not a black hole or empty meaning,

but a circular assertion of anti-nature, of synthetic actuality. The record,

which had been forgotten as item, as disc, is brought back into visibility,

by the coloured vinyl - of course in combination with the miniature artwork

of the picture cover. This should not be confused with later attempts to stimulate

collectability and sales with picture discs or limited editions. The coloured

disc hoped to detonate a mini-shock, at least a surprise as it was slipped from

the cover. The record stopped being natural, a hippy dream where the listener

gazes at beautiful people photographed against shrubs and trees, the hippy dream

of an unsullied life. Punk made pop music historical and artificial once more.

It devastated the romantic idyll.  With

punk the single came back into its own - famously ousting the concept album's

languor. It was an assertion of vinyl importance, before or beyond the concept.

It understood itself as the short sharp shock, just as Wyndham Lewis before

it had understood the end of painterly duration for producers and consumers

in 'Orchestra of Media', which insisted on abandoning oil paint in favour of

other instruments and media.

With

punk the single came back into its own - famously ousting the concept album's

languor. It was an assertion of vinyl importance, before or beyond the concept.

It understood itself as the short sharp shock, just as Wyndham Lewis before

it had understood the end of painterly duration for producers and consumers

in 'Orchestra of Media', which insisted on abandoning oil paint in favour of

other instruments and media.

The surfaces of cheap manufactured goods, woods, shell, glass etc already appreciated

for themselves and their possibilities realised, have finished the days of fine

paint. (Blast p142)

Punk's equivalent was plastic and formica. Though the point was not to represent it, but to appreciate it in itself. Punk was a populist modernism which reached a mass audience: punks could only look on with horror as the academic epigones, who had never been to the gigs and never dyed their hair pink, took on the philosophy pf postmodernism and took over the academy, declaring that 'high modernism' was an enemy of the people, and that consumer culture provided audiences with everything they need. Giants had been replaced with dwarves, and champagne with a linger aftertaste which was repulsive.

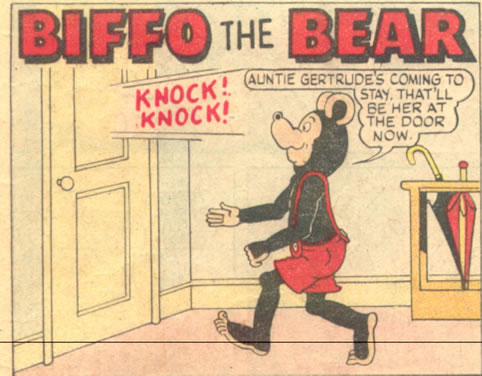

Materialist cultural analysis can easily claim the human universality of themes like sex and shit and dogs. By making Diogenes his anti-christ, Peter Sloterdijk has already proved as much. It is less clear what parts culture and anti-culture make up a genre like punk. As the conclusion of this talk, we would like to present some slides taken from The Beano, a comic which was read by all children in Britain thoughout the 60s and 70s, and which definitely had some influence on Punk Rock. Since Punk became an international export, whereas The Beano has remained a native phenomenon, perhaps you call help us judge the extent to which it shaped Punk.

Collour was what made the comic so attractive. It's used sparingly, thus keeping the price down. Simple black-and-white is alternated with black-and-red-and-white, then there's colour for front and back and the magnificent centre-fold of The Bash Street Kids. There's a certain pecking order - it's noticeable that the funnier strips with the stronger characters get the extra red, and everyone agrees that The Bash Street Kids are the comic's high point. This was in an era before newspapers were printed in colour, though on Sundays there were glossy 'colour supplements' full of photographs and advertisments featuring models, cars, liquor and cigarettes (none of which were of interest to children). Supplied with a Beano and a packet of 'Refreshers', 'Opal fruits', 'Wine Gums or a handful of four-a-penny 'Fruit Salads', a child's pocket money seemed to purchase riches unknown to adults. In this sense, The Beano was providing the kind of infantile pleasure stimulated by multicoloured wooden beads strung across a baby's pram. Beanos tended to be kept at ground level - you could locate them quickly even in an unknown newsagent. The stories are told from the point of view of children, continually at war with parents, teachers and policemen. At first, the cover featured 'Biffo The Bear', an unaccountably petit-bourgeois character who was forever fussing about his carpet, curtains and pictures. No less than Odysseus, Biffo The Bear enacted symbolic narratives whose significance for philosophy could far outway his seemingly humdrum existence.

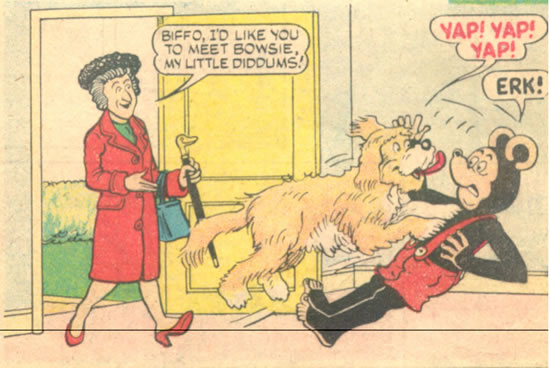

Here Biffo The Bear goes to answer the door. His Auntie Gertrude is coming to stay (unlike most other characters in The Beano, Biffo The Bear is a charcter of strict routine and social arrangement).

Unfortunately, she has brought with her a pet spaniel named Bowsie. In his unbridled canine enthusiasm, he not only knocks over poor Biffo, but threatens his precarious status as petit-bourgeois and semi-human. After all, Biffo wears shorts and braces (though no shirt), but the dog is naked!

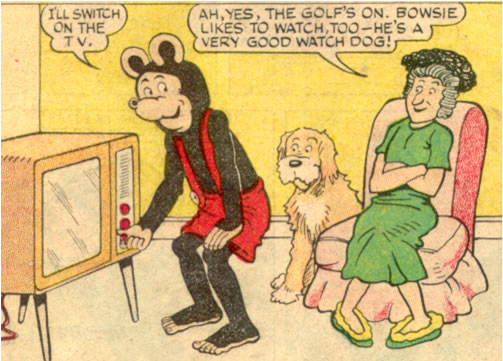

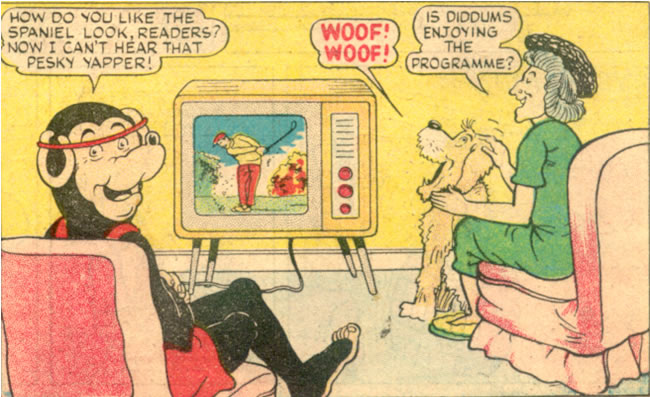

Biffo resorts to the standby of human beings who do not wish to communicate with each other, and switches on the TV, handing over his consciousness to be administered by the mass culture industry. Auntie is pleased that they can watch golf, probably the most boring sports programme possible. She also makes a pun: the dog likes TV, he is a very good 'watch dog'. My experience was that, as a child, such puns were more like mental tests than jokes. They never made me laugh. I frowned, 'got' them, and then moved on (in fact, it was only in my 20s that The Beano used to make me laugh out loud). The change in status between the working dog of the countryside - whose task is to 'watch' the sheep - and the ornamental 'little diddums' is indicative of the petit-bourgeois milieu inhabited by Biffo and his Auntie. Biffo occasionally works as a keeper in the zoo, but for a householder he has an inordinate amount of leisure. One suspects a private income or stipend of some kind. This distance from regular employment makes him subject to numerous neuroses, often centred on housework.

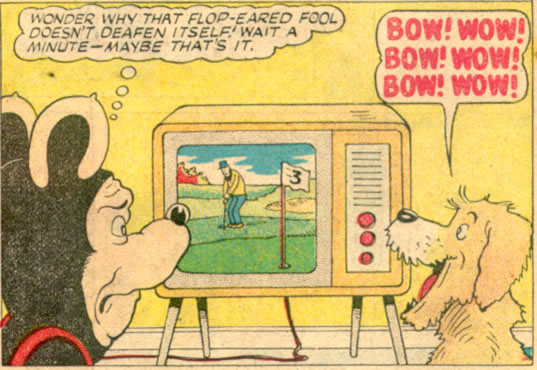

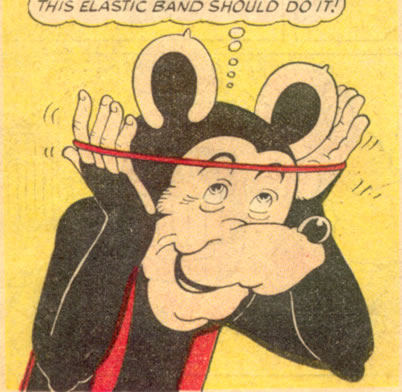

Unfortunately, the dog enjoys watching golf on TV so much, he begins barking. Biffo wonders whu the 'flop-eared fool' does not deafen itself. However, this gives him an idea. He takes a rubber band and puts it in his head, pressing his ears down against his head.

Biffo's solution to the TV-dog problem is fraught with paradox. He prevents himself hearing the dog, but he also cannot hear the commentary coming from the TV. The totality of the golf game will now become incomprehensible, its narrative and dramatic logic reduced to a series of strikes. On the screen, the golfer is missing the ball and instead sending up pieces of turf. It is as if the game itself has got caught in Biffo's self-defeating logic. Biffo has closed his ears to the voice of nature in order to concentrate on mass-cultural delusion, but in so doing has rendered that delusion incomprehensible, reduced it to an endless series of missed strikes.

He asks the readers if they like his 'spaniel look' - spaniels are famous for their ingratiating, fawning characters - but has made himself deaf to any reply. This is surely symbolic of the petit-bourgeoisie, deaf to criticisms of their own self-inflicted limitations, yet still confident they are 'doing the right thing'?

Interpretations of Biffo The Bear like the above tend to become parodies of Adorno's method in Dialectic of Enlightenment; Biffo is so isolated and singular, any social meaning imposed on the strip feels like a ridiculous imposition. This cannot be said of the character who replaced him. Biffo was deposed from the front cover in late 1974. Dennis the Menace, who had previously been on the back page, now occupied both front and back. Dennis has a dog Gnasher, an extraordinary prosthesis, seemingly an autonomous bundle of Dennis's wild hair. They are prototypical punk rockers, allergic to 'softies', flowers and perfume - though Dennis sprouted his dreadlocks in the late 60s, independent of any fashions connected with music. Benjaminites will be upset to learn that the prototypical softie is called Walter. He has a friend with the upper-class name Bertie Blenkinsop, and he has a pet poodle named Foo Foo. The war against them is one of urchin versus posh kid, mongrel versus thoroghbred.

Was the strip homophobic? Probably, but that hasn't stopped the gay community plundering The Beano for imagery, though maybe not quite as much as they did Enid Blyton's Noddy and Big Ears (probably indicating more real affection for the former).

The black scribble which represents Dennis's hair and Gnasher beautifully sets off the rest of the colours in this strip. In Goethe's Faust, Mephistopheles first appears to Faust and Wagner in the shape of a black poodle. Faust is fascinated by the multiple colours and sparks that fly around him. The point is not that the designers of Dennis The Menace were making a reference to Faust, but that Goethe was interested in perceptual phenomena, and a large area of black is just the thing to make colours shine bright. The Beano artists made the same discovery.

Minnie the Minx is a riotous little girl with a very funny relationship to her long-suffering father, who like most long-suffering adults in The Beano has a long face and a long, protruding nose. Minnie is a very dynamic chases with a lot of chases, action and much destruction of furniture.

Minnie always has a theme - or excuse - for causing mayhem. In this strip she's attempting to swat a fly.

It is hard to describe the peculiar pleasure of the Bash Street Kids. Puns are difficult in other languages - once they've been explained they don't seem funny. For instance, the story about a design school from the issue of 31 January 1976.

The Bash Street Kids are an anarchic collective, each with a distinct character. They are working class and thoroughly opposed to the upper-class Blob Street gang. When the Sex Pistols named themselves Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious and presented the appearance of a bunch of naughty street kids playing at pirates, it's difficult not to see an influence stemming from The Bash Street Kids. What was amazing with Punk was that these characters had somehow leapt out of the comic and appeared to be scandalising newspaper columnists, royalists and police officers all over the country.

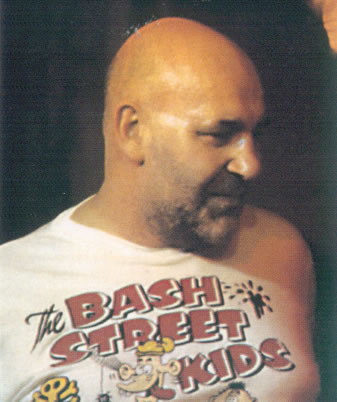

Lol Coxhill is a soprano saxophonist who has been involved with practically every significant wave of music in Britain. His latest 2CD set, a retrospective - Spectral Soprano [Emanem 4204] includes a bop ballad from the 50s, beat-boom R&B from the 60s, hippie experimentation with electronic keyboards and a saxophone concerto backed by the London Improvisers Orchestra. In the early-70s he was musical director of a roving street theatre named Welfare State. His first album was released on John Peel's dandelion label. If music is innovative, populist and accessible but defiantly uncommercial, he's there. In 1977, he toured with the punk group The Damned, who recorded a track named 'Grimly Fiendish' after a strip drawn by Leo Baxendale, the inventor of The Bash Street Kids. He has played at Company Week with guitarist Derek Bailey, and now records mainly for the free-improvisation label Emanem. One of the tracks on his retrospective is drum'n'bass by Paul Schütze. It's completely natural that he should wear a Bash Street Kids t-shirt featuring Plug, the famously 'ugly' character.

The Bash Street Kids insist on fun and transformation and constantly come into conflict with authority. They particularly love it when figures of speech become actualities, and phrases which refer to wild animals or overgrown jungles or which have double meanings suddenly become entities in real life. Like in a dream or a poem, the distinction between images and what they refer to keeps being dissolved. This is because the strip is predicated upon jokes - an involuntary response on the part of the reader - not upon maintaining the conditions of illusion. Any artist who can take this aesthetic seriously is keeping open a channel of communication with the utopian delight of childhood, and can inform revolutionary art with a sense of pleasure it so desperately needs. As we hope we've showed, this insistence on libidinal gratification rather than organised culture is not inimical to marxism, but actually forms one of its fundamental drives: to shape and transform the world, and pursue a dialectic between 'mere ideas' and 'images' and reality.