Get You Back Home

The

Punk

Paper: A Dialogue

Esther

Leslie and Ben Watson

B:

When formulating his ideas about money and capital - sketches for the great

work Capital which were eventually published under the name Grundrisse - Karl

Marx developed a critique of conventional ways of writing history. When people

relate history as a succession of events unfolding in time, they distort reality

by assuming that concepts that were actually the

product of historical developments were always in existence. He complained that

people project back concepts like human equality, money-making and commercial

calculation into the mists of time, when these are actually only possible once

there is an infrastructure of trade, roads and manufacture. If Punk

is approached retrospectively as a successful pop

phenomenon, a fashion wave, a raft of new celebrities, our understanding is

coloured by a similar kind

of back projection. Commercialised anger didn't exist before punk - rap would

have been impossible without it - and situationist ideas now accepted as commonplace

were inaccessible to anyone but intellectuals. At

the time, Punk felt like risk and truth, not scam, celebrity and money.

B:

When formulating his ideas about money and capital - sketches for the great

work Capital which were eventually published under the name Grundrisse - Karl

Marx developed a critique of conventional ways of writing history. When people

relate history as a succession of events unfolding in time, they distort reality

by assuming that concepts that were actually the

product of historical developments were always in existence. He complained that

people project back concepts like human equality, money-making and commercial

calculation into the mists of time, when these are actually only possible once

there is an infrastructure of trade, roads and manufacture. If Punk

is approached retrospectively as a successful pop

phenomenon, a fashion wave, a raft of new celebrities, our understanding is

coloured by a similar kind

of back projection. Commercialised anger didn't exist before punk - rap would

have been impossible without it - and situationist ideas now accepted as commonplace

were inaccessible to anyone but intellectuals. At

the time, Punk felt like risk and truth, not scam, celebrity and money.

Of course,

Marx isn’t stupid enough to announce - in the approved Deleuzian manner - that

all we need to do is to simply rid ourselves of concepts. He began The German

Ideology by accusing the Young Hegelians of plotting a revolt against the rule

of concepts [Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The German Ideology, 1846, first

published 1932; translated W. Lough (pp. 19-92), Clemens Dutt (pp. 94-451) and

C.P. Magill (pp. 453-540), London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1976, p. 23], and

pointed out that ‘all relations can be expressed in language only in the form

of concepts’ [Ibid, p. 363]. There is no non-conceptual access to the meaning

of the past. In order to understand the past without hypostatising current concepts

as eternal fixtures, we need to determine the sequence of conceptual categories

in modern bourgeois society, which is ‘precisely the opposite of that which

seems to be their natural order or that which corresponds to historical development’

[Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 1857, first published in Russia 1939/41, in Germany

1953; translated Martin Nicolaus, London: Penguin, 1973, p. 107]. The Sex Pistols

were not an innocent teenage band who were sucked into the endeavours of capital,

they were a destructive consciousness which applied the most advanced critical

ideas of their time.

They would

not accept the postponement latent to capital's wagers on the productivity of

future labour. These principles were misinterpreted in the mass media throughout

the 80s and 90s. Only now, with the emergence of the anti-capitalist movement,

can Punk's anti-commodity populism be properly understood.

E: A century

before Punk emerged as latest rebel youth subculture,

the word itself meant something else: it meant something worthless, foolish,

rubbish, empty talk, nonsense: such that Carlyle could speak of ‘phosphorescent

punk and nothingness’ However when it came to future

dreams for colour schemes punk preferred fluorescence’s

immediate shock of the intensified glow to phosphorescence’s postponed illumination

of its self in the darkness. Fluorescence holds nothing back for later - like

punk, its mode is the mode of anti-interiority,

denial of romantic self, a cheap trick, a cheap trip without innerness, an upfront,

slap in the face of public taste.

B: The reason

that Marxism has a poor reputation in cultural analysis is to do with confusion

over the necessary granularity required to grapple with specific experiences.

Simple statements about capital, proletariat and commodification are in danger

of sounding true for all time - or at least, true from the late eighteenth-century

through to the twenty-first, which from the point of view of one’s personal

relationship to musical fashion, can look like the same thing. In order to look

at Punk, the Marxist needs to build on the substantive

categories of capital and class, but beyond that, must denature the categories

specific to pop music under capitalism. In other words, Punk

cannot be understood by simply narrating its events in chronological order,

as Jon Savage did in England’s Dreaming. Its determinations can only be unpicked

by examining the latest developments in the contradictions it exploited, which

means understanding the current relationship of capital and commodification

to musical truth. The current marketing of The Strokes as "the most shaggable

band in Britain", the issue of the black blocks in Genoa last July and

the challenge to the radicalism of rock guitar-sound introduced by Derek Bailey

are all more relevant to understanding the politics of the Sex Pistols than

anecdotes about the Jubilee boat trip. That is why Jon Savage’s narrative betrays

and tames the very movement it sought to explain: it projects back the success

of Punk into its history, and therefore presents

yet another cosy and positive tale of rags-to-riches. Since this is also the

story of Jon Savage, now a successful member of the Popsicle Academy, we are

really reading autobiography in drag.

One way of

blowing apart the dead inevitability of history written with hindsight - its

placid affirmation of the status quo - is Walter Benjamin’s method of seizing

on a significant detail. This was actually a development of Benjamin’s reading

of Marx’s Capital. Benjamin’s hallucinogenic focus on a single detail jolts

a moment from its place in a preordained sequence of events, and lets in the

multivalent possibility inherent in human action. As Hegel said in the smaller

Logic, para. 143, ‘Viewed as an identity in general, Actuality is first of all

Possibility.’ [G.W.F. Hegel, Logic, 1817/1827, translated William Wallace, 1873,

Oxford: OUP, 1975, p. 202]. This is an insight that Savage never dreamed of.

The Punk story told in terms of chart placements and fame immediately puts Punk

back in the pop logic it was a protest against, whereas reveries about shopping

schemes, council tenancies, bondage and Day-Glo

can take us back into the first moments of Punk’s

immediacy, its shock and exhilaration - the heretical idea of living historically

instead of at the behest of the needs of capital accumulation. No past, no future,

no capital, no mortgage payments.

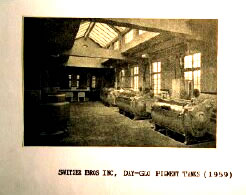

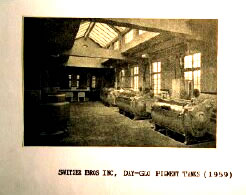

E: Day-Glo

was the colour of choice for punk. Day-Glo

had been around for some time when punk appropriated it. In the 1930s, after

one of them received a bonk on the head and a spell of recuperative treatment

under ultra-violet light, Bob and Joe Switzer, eager young experimenters, were

mucking around with dyes and resins to make colours that were brighter than

normal and glowed under u.v. light. They used these new fluorescent colours

in their hokey little magic shows. The colours were eye-catching, because they

shone brighter than other colours. It was as if a new part of the spectrum had

been discovered. Day-Glo

colours are composed of fluorescent materials. Colour arises in ordinary objects

through selective absorption. Ordinary paint absorbs some of the spectrum from

white light and reflects the rest. Red paint absorbs blue and yellow, resulting

in the scattering back of only red. Day-Glo

paints do not simply scatter back light from the visible part of the spectrum.

They can also take shorter wavelengths (usually ultraviolet) that are invisible

to our eyes and they re-emit the energy by converting it into photons of longer

wavelength. Thus, ultraviolet light goes in and its energy is converted into

visible light emitted by the chemicals in the paint, creating the bright fluorescent

quality. Fluorescent materials emit more red light for example, than ordinary

red objects because they take some of the ultraviolet light that is invisible

to our eyes and emit it as visible light. Day-Glo

lets more be seen - it shines brighter. In 1936 the Switzer brothers set up

a firm in Cleveland. War came and the colours found military application in

bright signal panels used by the army, but peace put them back into civilian

use on billboards, in safety signage and promotional publicity, and soap powder

boxes. Outside the military context, Day-Glo was associated with vulgarity -

the too obvious - the screamingly evident.

In the

1950s the name Day-Glo was trademarked and in the late 1960s the company formally

changed its name from Switzer Bros Inc to Day-Glo Colour Corp. In their names

one can hear the poetry of science, industry and space exploration. The full

trademarked pigment set comprises Neon Red, Rocket Red,

Fire Orange, Blaze Orange, Arc Yellow, Saturn Yellow, Signal Green, Horizon

Blue, Aurora Pink, Corona Magenta, Strong Corona Magenta, Strong Saturn Yellow.

Day-Glo

first infiltrated the American landscape as entertainment then as an alert to

danger and later as commodity shriek. A fan of Ultraviolet light, who runs a

website dedicated to its discussion, writes of a trip to Disneyland in the Summer

of 1961. There he rode through psychedelic landscapes - such as the Alice

in Wonderland ride - made of Day-Glo

scenes extra-illuminated

under u.v. light. Day-Glo

fluorescent paint was

fairly easy to get hold of in the 1960s - it became a household word through

Tom Wolfe’s book on Ken Kesey and the Pranksters. It remained a bad taste product,

acceptable only to commercial art, where Psychedelia found a use for it in posters

and it found its way into film. In the entry on the word Day-Glo

the OED quotes an article

from the Listener, from 1968, which condemns the use of flashing Day-Glo

colours as vulgar signal

of an orgasm in a film by Jack Cardiff. The hippies used Day-Glo

in their cultural artefacts,

and even on their bodies, but theirs was an attempt to paint over the world

in the colours of their hallucinogenic trips. Day-Glo

was being taken into

the student bedroom, the kids’ blacklit den where individual mediation could

hinge on the wonders of a perceptual trick that disappeared when normal electricity

resumed.

In the

1950s the name Day-Glo was trademarked and in the late 1960s the company formally

changed its name from Switzer Bros Inc to Day-Glo Colour Corp. In their names

one can hear the poetry of science, industry and space exploration. The full

trademarked pigment set comprises Neon Red, Rocket Red,

Fire Orange, Blaze Orange, Arc Yellow, Saturn Yellow, Signal Green, Horizon

Blue, Aurora Pink, Corona Magenta, Strong Corona Magenta, Strong Saturn Yellow.

Day-Glo

first infiltrated the American landscape as entertainment then as an alert to

danger and later as commodity shriek. A fan of Ultraviolet light, who runs a

website dedicated to its discussion, writes of a trip to Disneyland in the Summer

of 1961. There he rode through psychedelic landscapes - such as the Alice

in Wonderland ride - made of Day-Glo

scenes extra-illuminated

under u.v. light. Day-Glo

fluorescent paint was

fairly easy to get hold of in the 1960s - it became a household word through

Tom Wolfe’s book on Ken Kesey and the Pranksters. It remained a bad taste product,

acceptable only to commercial art, where Psychedelia found a use for it in posters

and it found its way into film. In the entry on the word Day-Glo

the OED quotes an article

from the Listener, from 1968, which condemns the use of flashing Day-Glo

colours as vulgar signal

of an orgasm in a film by Jack Cardiff. The hippies used Day-Glo

in their cultural artefacts,

and even on their bodies, but theirs was an attempt to paint over the world

in the colours of their hallucinogenic trips. Day-Glo

was being taken into

the student bedroom, the kids’ blacklit den where individual mediation could

hinge on the wonders of a perceptual trick that disappeared when normal electricity

resumed. It

took punk to fully assimilate Day-Glo

without transforming

it - that is vulgarity and all - in fact because of its bargain-basement, eye-catching

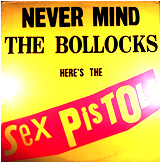

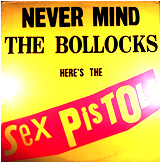

impudence. Jamie Reid’s cover for Never Mind the Bollocks

modelled itself on a crude supermarket display. This was consumer society staring

itself in the face. Art, as ever, was behind the times when Peter Halley began

to use Day-Glo

paints in his abstractions

in the 1980s. Punk had already camouflaged itself in the colours of the antagonist.

It

took punk to fully assimilate Day-Glo

without transforming

it - that is vulgarity and all - in fact because of its bargain-basement, eye-catching

impudence. Jamie Reid’s cover for Never Mind the Bollocks

modelled itself on a crude supermarket display. This was consumer society staring

itself in the face. Art, as ever, was behind the times when Peter Halley began

to use Day-Glo

paints in his abstractions

in the 1980s. Punk had already camouflaged itself in the colours of the antagonist.

B:Apart from

his absurd tease that the Sex Pistols were not a punk band, Stewart Home's analysis

of punk - because it has some relation to dialectical non-affirmative concepts

- has been the most helpful. In maintaining that its root politics were either

anarchist or fascist - by which he means irretrievably petit bourgeois and individualist

- he breaks out of the narrow view that pop may only be discussed in its own

terms: a stupid and inert reflection of the economic categories of its primary

distribution. If music is not real unless it reaches the charts, if there is

no everyday life outside practices which allow capital to realise surplus value,

then there is no escape from ideology, everything is a sequence of deracinated

images, and when I take a shit, I don't exist.

This is not

the consciousness addressed by Punk. Indeed, Punk

refurbished chart music and mass celebrity as potential sites for critique,

bringing back into social dialogue drives and ambitions which would otherwise

have been driven underground into daydreams, classical revolutionary politics

or backwater academia. In Home's analysis, Punk is seen as a radical art practice,

and it is made to stand or fall by reference to the most advanced ideas of that

milieu, which means those of the Situationists.

However, in

performing his ideological critique of Punk, Home steers dangerously close to

an idealism which underestimates the intelligence of the real, and only pays

attention tthose who treated Punk as a soapbox for political broadcast. Situationist

rhetoric was dependent on the particular situation of artistic radicals in post-war

Paris: an artistic world capital that was losing hegemony to New York, a left

establishment which had made a historic compromise with Communist state-capitalism

in Russia, and a surrealism deaf to the claims of music as a truth-testing of

social repression. Once transplanted to London, situationist ideas entered into

a completely different relation to the establishment. There was no question

of organising advanced artists to take seriously a surrealist objection to bourgeois

social relations, since modern art in Britain - Francis Bacon, Henry Moore and

Frank Auerbach - was a parochial parody of the movements which had swept Rome,

Moscow, Paris and Berlin, utterly uncomprehending of the continental avantgarde’s

anti-art dynamic.

E: The problem

of English art is a long-standing one. The seeds of English visual radicalism

have been few and far between, and generally imported.

B: To those

fifty readers addressed by Guy Debord’s newsletter Potlatch, the next technical

step for modern art beyond Lettrisme and Cobra was absolutely clear: on the

basis of Jorn’s comparative vandalism and a historical-materialist understanding

of disorder and chance, artist organisation and collective resistance to American

museums and collectors seemed both possible and necessary.

In Britain,

John Berger saluted the Situationists from the pages of New Society, but the

idea of modern artists resisting the commercial or establishment recuperation

of their art was simply ridiculous. The establishment didn’t ‘recuperate’ the

technically-advanced art of J.H. Prynne and Bob Cobbing and Tom Raworth, it

simply ignored it, let it rot on the vine. Only Britain could have incubated

a sorry development like Art & Language, who found they had to commodify

critical concepts themselves in order to unfurl their phony denunciation of

such commodification (and whose most recent edicts take the radical step of

quoting Adam Ant). When London situationists fly-posted a comic denouncing the

hippies on the office door of the International Times, the paper responded by

printing it on their cover: critiques which had Parisian bigwigs resorting to

the lawcourts and the cops were simply grist to London’s early-70s counter-culture

farrago of revolution and commerce. The most alert British receiver of situationist

ideas was Tim Clark, who promptly parlayed Debord’s historical-materialist insights

into a novel brand of pseudo-Marxist, anarcho-liberal academia called the New

Art History.

E: The problem

of this, of course, was that it still believed art history was worth doing.

That, at least, was marginally better than believing art was worth doing.

In

1914, a member of the Rebel Art Centre, Wyndham Lewis launched a Vorticist magazine.

Lewis’ Blast was supposed to be a celebration of the blast furnaces of

the industrialized Midlands and North. Blast also suggests a hygienic

gale from the North. The emblematic representation of the vortex on the first

pages of Blast is a figuration of a storm-cone with the apex up: a signal

used by coastguards to represent strong winds from the north. Blast lends

perhaps the visual and polemical aesthetic of the punk fanzines. Blast

– with its glorious outrageously luridly pink cover and heavy anonymous blockish

black typography and polemical rants – was just as shocking as the Sex Pistols

Never Mind the Bollocks LP cover.

In

1914, a member of the Rebel Art Centre, Wyndham Lewis launched a Vorticist magazine.

Lewis’ Blast was supposed to be a celebration of the blast furnaces of

the industrialized Midlands and North. Blast also suggests a hygienic

gale from the North. The emblematic representation of the vortex on the first

pages of Blast is a figuration of a storm-cone with the apex up: a signal

used by coastguards to represent strong winds from the north. Blast lends

perhaps the visual and polemical aesthetic of the punk fanzines. Blast

– with its glorious outrageously luridly pink cover and heavy anonymous blockish

black typography and polemical rants – was just as shocking as the Sex Pistols

Never Mind the Bollocks LP cover.

Designed

in 1913, printed in 1914, Blast was designed to be a verbal expression

that could be adequate to the ‘stark radicalism of the visuals’ that Lewis had

been developing in the previous years. (Letter to Partisan Review, from

Lewis, 1949, quoted in Richard Cork, Vorticism, I, p260.) The Pall Mall

Gazette, describing the cover as the colour of 'chill flannelette pink' added

that the colour 'recalls the catalogue of some East End draper, and its contents

are of the shoddy sort that constitutes the East End draper's stock'.

Blast

was written by self-styled ‘Primitive Mercenaries’ (p30), savage artists mingling

in the ‘enormous, jangling, journalistic fairy desert of modern life’ (p33).

In the glorious pink volume of Blast no.1 (of only 2) Ezra Pound presents

some condensed Imagist poems on colour, artifice and chemicality.

Women

Before a Shop

The gewgaws

of false amber and false turquoise attract them,

Like to

like nature. These agglutinous yellows.

L’Art

Green

arsenic smeared on an egg-white cloth,

Crushed

strawberries! Come let us feast our eyes.

The

New Cake of Soap

Lo, how

it gleams and glistens in the sun

Like the

cheek of a Chesterton.

(all in Blast

1, 49)

These slogan

poems cough up the major concerns of London Vorticism. In the first poem, consuming

women are attracted to baubles, to the fakery of the commercial, a cheap trick

to pull in the punters. They are attracted because they themselves no different,

like eyes up like, each as artificial, false and hideous as the other. The second

poem vituperates against art – in the modish French sense – as a mélange

of poisonous tint and damaged nature on canvas. A feast for the eyes indeed

bitterly evokes a deadly mess, of faked and ruined nature for those who know

no better. The third poem parodies formal appreciation on the part of art lovers,

by conceiving the aesthetic pleasures of bar of soap, cleanliness being its

aim, just like the good clean English middle-class fun of G.K. Chesterton.

For direct influence between the old guard punk and the purveyors of English

Vorticism, see the following: Mark E. Smith, "Heroes, part I: His Influences"

Melody Maker, Sept. 27, 1986, p. 33

'He was a funny old stick, Wyndham Lewis, the most underrated writer this

century. I can't believe how good his stuff is when I'm reading it. He was

a much better writer than he was a painter. People always say that Paul Morley

ripped off Lewis, which is bollocks. WE ripped off Lewis, and Morley stole

his ideas from us! The thing that pissed me off is that ZTT uses his ideas

and then put them into a context that Lewis would have hated. He loathed the

futurists. His stories are great; things like 'The Crowd Master' in Blast.

What a great title for a story. Wyndham Lewis is so real and so now. He wrote

a book about Hitler in 1934 saying that this is maybe the way forward and

was condemned during and after the war for being a Nazi. Yet in another book,

'Rotting Hill', he says he wrote an essay in 1938 to say that he was completely

wrong and that Hitler had to be stopped. The critics made sure he was only

remembered one way - the wrong way. He was a real man though. He'd always

be the first to condemn himself if he got something wrong. He went for the

critics before they went ever got to him. I like people than can admit to

their mistakes. When people ask me about The Fall back in '77 and the whole

punk thing I say it was shit. Everyone hated us. Punk bands hated us. Even

we hated us! I'm not going to lie about it. It's hard, but I like people that

are real and tell the truth. His books are hard to read but if you stick with

them they're great. "Rude Assignment' - what a title! 'Rotting Hill'

is the greatest phrase I've heard in my life. It's so simple you'd never think

of it. The things he was talking about in 1911, people are just beginning

to talk about now. A man years ahead of his time.'

Pound had

been requested to submit some ‘nasty’ poems to Blast. (see Cork, Vorticism).

The nastier the poems the better. But in what does their nastiness lie: in the

reference to the modern age’s fakery and chemical inauthenticity. This acerbic

squeal found an echo 60 years later in Polystyrene’s lyrical rejection of germ-free

adolescence and postwar plastics, engine of a new economy, in ‘The Day the World

Turned Dayglo’ – a chemical retort to the internalized hippy-trip of ‘Lucy in

the Sky with Diamonds’:

I

clambered over mounds and mounds

Of

polystyrene foam

Then

fell into a swimming pool

Filled

with fairy snow

And

watched the world turn

Day-glo

you know you know

The

world turned day-glo you know

I

wrenched the nylon curtains back

As

far as they would go

Then

peered through Perspex window panes

At

the acrylic road

I

drove my polypropylene car

On

wheels of sponge

Then

pulled into a Wimpy bar

To

have a rubber bun

The

x-rays were penetrating

Through

the Latex breeze

Synthetic

fibre see-thru leaves

Fell

from the rayon trees

Polystyrene

woke up in a world that was synthetic, just as the Vorticists had woken up in

a world that was machinic. While Lewis publicly scorned Marinetti’s ‘Futurist

gush over machines, aeroplanes, etc.’ he was impressed by Marinetti’s idea that

humans are changed by living in cities with communications and transport at

their disposal, and affirms a dada manifesto from 1918 which describes the dada

sound poem as the sheer noise of urban existence, the screech of tram brakes,

which wipe out traces of old-style individuality. In Vorticist stylisation the denial of the human form is executed in a heightening

of the flat surface of the image, and in a paring down of the elements involved.

Lewis presents the human form like girders and industrial shapes. He writes:

THE ACTUAL HUMAN BODY BECOMES OF LESS IMPORTANCE EVERY DAY. It now literally

EXISTS much less. Lewis headed towards a sort of masculinized androgynousness.

Interiority is expelled like dust by a sharp gust of Blastish air.‘Never

trust a hippy’ cautioned a Jamie Reid poster in lurid yellow - its exhortation

was against nature.

It is irresistible. Lewis in ‘The London Group’ insisted on ‘LIFE not ‘Old Masters’

and the rejection of art which is dead with heavy woodness or stone, instead

- 'here flashing and eager flesh, shiny metal.' (Blast p77) Shiny metal,

chrome had paled as the 50s Americana dream was tarnished, but plastics were

the new flexible friend of global economies. Punk’s postwar version of Lewis’

material desideratum forwarded not the machinic society but the plastic consumer

society. Polystyrene again:

In Vorticist stylisation the denial of the human form is executed in a heightening

of the flat surface of the image, and in a paring down of the elements involved.

Lewis presents the human form like girders and industrial shapes. He writes:

THE ACTUAL HUMAN BODY BECOMES OF LESS IMPORTANCE EVERY DAY. It now literally

EXISTS much less. Lewis headed towards a sort of masculinized androgynousness.

Interiority is expelled like dust by a sharp gust of Blastish air.‘Never

trust a hippy’ cautioned a Jamie Reid poster in lurid yellow - its exhortation

was against nature.

It is irresistible. Lewis in ‘The London Group’ insisted on ‘LIFE not ‘Old Masters’

and the rejection of art which is dead with heavy woodness or stone, instead

- 'here flashing and eager flesh, shiny metal.' (Blast p77) Shiny metal,

chrome had paled as the 50s Americana dream was tarnished, but plastics were

the new flexible friend of global economies. Punk’s postwar version of Lewis’

material desideratum forwarded not the machinic society but the plastic consumer

society. Polystyrene again:

I

know I’m artificial

But

don’t put the blame on me

I

was reared with appliances

In

a consumer society

…

My

existence is illusive

The

kind that is supported

By

mechanical resources

…

I

wanna be instamatic

I

wanna be a frozen pea

I

wanna be dehydrated

In

a consumer society

Despite its

lurid appearance, The cover of Never Mind the

Bollocks was no cheap thrown together item – it relied on modern painterly

technologies. The printing process was difficult, because yellow is a ‘notoriously

bad colour to print as it shows up any impurities in the process very clearly.

And, although the sleeve gives the impression of being simple, it uses a series

of complex overlays. Fluorescent colours are hard to print as well, which doubled

the difficulty.’ (from The Incomplete Works of Jamie Reid p79). Reid

also says: ‘It was a feature of the finished sleeve that it deteriorated very

quickly: if left out in the sunlight, the yellow and the pink faded, just leaving

the black of the overlays.’ (p79)

Evanescence

and the mystique of fleeting intensity was arguably a core modernist theme,

and Lewis had affirmed it already in a comment of his in the essay ‘Futurism,

Magic and Life’ (Blast 1, p134) where he notes how the most perishable

colours in painting (such as Veronese green, Prussian Blue, Alizarin Crimson)

are the most brilliant. So that which burns brightest burns most briefly, and

in true modernist fashion brilliance must be but fleeting, timely, not eternal,

a coincidence of moment, viewer and object. Lewis proclaims of this: ‘This is

as it should be: we should hate other ages, and don’t want to fetch £40,000

like a horse" – asserting the desire not to be commodified and not to become

a part of the archive.

For Reid and

the Sex Pistols, the painstaking work on the cover paid off, for the sleeve

caused a fuss when it came out – mainly because it appeared to be the opposite

of what it was – shoddy, cheap and nasty – and also because it had an anonymity

as its theme – not only the cut out blockish – Blast-ish or newspaper

headline lettering – but also the lack of stars’ on the cover. No phosphorescent

stars sending back their celebrity light to illuminate the gloom of adolescent

fantasy – as The Clash, getting it so wrong would do with their first LP. The

Sex Pistols, of course, did enstage themselves, not on the covers but elsewhere

– however this self-display refused interiority, turning their selves into mannequins,

for Westwood’s clothes, McLaren’s game.

B:Interiority

is the last refuge of the petit bourgeois, as any reader of Ian Penman knows.

What Home objects to as the ‘anarcho-fascist’ politics of Punk is actually the

ideology of individualists and careerists - music journalists, record-company

men and petty academics - who refused to accept that Punk begged questions about

the wider class struggle. At the time, Rock Against Racism was not an option

anyone could refuse who was attendant to confusions created by McLaren’s use

of the swastika. Of course, it is now common knowledge

in Cultural Studies that Rock Against Racism was

manipulative, racist and oppressive to minorities, a historical revision which

could only be undertaken by people who never found themselves in a punk club

ordering drinks at the bar next to a British Movement organiser who is wearing

a union-jack-plus-swastika sticker, and harassing the Sikh behind the bar. Home

is these days gleefully separating himself from anarchism and calling himself

a council communist, but his situationist-derived fear of Leninism - a misconstruction,

since Guy Debord’s polemics were directed against the French Communist Party,

not the SWP - meant that he could not endorse Rock Against Racism at the time.

Having argued himself out of the swamps of anarchism, Home faces a stark political

choice between Leninism and liberalism

(in the absence of any contemporary current, his claim to be a "council

communist" amounts to political abstentionf).

Historically,

"radicals" like Crass who refused to take sides soon revealed themselves

as petit-bourgeois parasites eager to finance their own lives of "individual

freedom" in Ongar, Epping Forest - and, in

the case of the Poison Girls, the Sierra Nevada - through the proceeds of their

musical activities. Unlike subsequent imitations such as Red Wedge and Live

Aid, Rock Against Racism was not organised in order to promote stars and sell

records. It used the generalised impact of Punk - the formation of countless

bands looking for places to play - and struck bargains where a band’s desire

for exposure was exchanged for an explicit stand against racism. Of course,

there was much confusion and debate about race and class and integrity in these

bargains, but the emergence of Two Tone

proved that the idea of punky-reggae

parties - usually a couple of punk bands and a sound system - resulted from

real social interaction rather than marketable imagery. A comparison of the

revolutionary politics of Two Tone and On-U Sound - labels dedicated to racial

miscegenation - and, say, Factory or Creation

Records, demonstrates how even tacit racism holds back political consciousness

in popular music.

Why is the

radical working-class politics of Two Tone and On-U Sound not reflected in the

species of mixed-race cybermusic - house, acid, rave - celebrated by Kodwo Eshun?

The answer is that mystification

about the source of music via the commodity of the recorded format

suppresses the singularity of event that is required for political consciousness

and historical action. Disco and rave force consciousness inward and merely

facilitate mass drug-taking: individual solipsism and public idiocy. Hip Hop,

on the other hand, by making rhythmic interruption a source of pleasure and

continuity, is a revenge of the particular situation upon the generality of

the commodity. When the DJ scratches the record, all the preordained momentum

of a commodified music is suspended, allowing for the tabula rasa immediacy

which is the moment of authentic modern art - from the theatre of the absurd

through to Free Improvisation, a matter of creating pertinent situations.

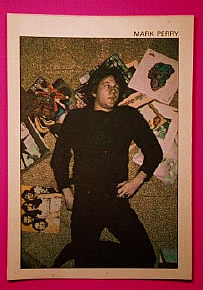

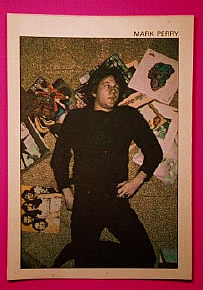

E: In Punk

hi and lo clash – they do not meld in a postmodern paradise. If the Situationists

are victory, punk is the tragedy, and postmodernism the farce. With punk died

truly righteous anger, the righteous anger that can say, as did Mark P. in a

1977 issue of Sniffin Glue (now quoted in the OED): ‘The sickest thing

is the Zandra Rhodes "punk chic" look.’. That can say, as Sid Vicious

did, "All Hollywood films are complete bollocks, the actors are only pretending."

B: General

recognition of the artistic depth and instrumental effectiveness of the Sex

Pistols and their records has led to many attempts to repeat their ‘moment’.

Whatever Home says about them, the Pistols are the reason we’re having this

conference. Without them, Punk would have been pub rock or American torn-tie

bohemia. One strand of interpretation decided that scandal, riot and offense

were the essence of Punk’s difference from rock music as normal. When Descension

- a band of cacophonic

free improvisors, including the guitarist from Whitehouse - supported Sonic

Youth at The Forum, they caused a riot among the fans. Thurston Moore skipped

up to the dressing room - ‘Gee, was that what the Sex Pistols were like?’. Actually,

as Steve Jones said towards the end of their brief period of media exposure,

‘What everyone seems to have forgotten is that the Pistols are actually rather

a fine dance band’.

When I saw the Pistols at the Royal Links Pavilion in Cromer, Norfolk, on Christmas

Eve 1977, they played an immaculate set, probably the best rehearsed rock band

I’ve seen outside the Magic Band, Devo and Bow Wow Wow. When

they named their album Never Mind The Bollocks, the Pistols meant that the media

furore and their own shenanigans were to be ignored. The essence of their statement

was sonic. The idea of them as merely a media event is a postmodernist evasion

of musical materialism.

The

Day-Glo

coloured vinyl

punk record is not a black hole or empty meaning,

but a circular assertion of anti-nature, of synthetic actuality. The record,

which had been forgotten as item, as disc, is brought back into visibility,

by the coloured vinyl – of course in combination with the miniature artwork

of the picture cover. This should not be confused with later attempts to stimulate

collectability and sales with picture discs or limited editions. The coloured

disc hoped to detonate a mini-shock, at least a surprise as it was slipped from

the cover. The record stopped being natural, a hippy dream where the listener

gazes at beautiful people photographed against shrubs and trees, the hippy dream

of an unsullied life. Punk made pop music historical and artificial once more.

It devastated the romantic idyll.

The

Day-Glo

coloured vinyl

punk record is not a black hole or empty meaning,

but a circular assertion of anti-nature, of synthetic actuality. The record,

which had been forgotten as item, as disc, is brought back into visibility,

by the coloured vinyl – of course in combination with the miniature artwork

of the picture cover. This should not be confused with later attempts to stimulate

collectability and sales with picture discs or limited editions. The coloured

disc hoped to detonate a mini-shock, at least a surprise as it was slipped from

the cover. The record stopped being natural, a hippy dream where the listener

gazes at beautiful people photographed against shrubs and trees, the hippy dream

of an unsullied life. Punk made pop music historical and artificial once more.

It devastated the romantic idyll.

With punk

the single came back into its own – famously ousting the concept album’s languor.

It was an assertion of vinyl importance, before or beyond the concept. It understood

itself as the short sharp shock, just as Wyndham Lewis before it had understood

the end of painterly duration for producers and consumers in ‘Orchestra of Media’,

which insisted on abandoning oil paint in favour of other instruments and media.

‘The surfaces

of cheap manufactured goods, woods, shell, glass etc already appreciated

for themselves and their possibilities realised, have finished the days

of fine paint.’ (Blast p142)

Punk’s equivalent

was plastic and formica. Though the point was not

to represent it as such, but to appreciate it in itself.

B: This materialism

extended to the sound. The musical power of the Sex

Pistols was utterly shocking. Cook and Jones managed

to reproduce the push’n’pull of adults fucking, the objective, mindless, ineluctable

squelch of what Wilhelm Reich called ‘cosmic plasmatic sensation’ - a sound

designed to terrify infants and fascinate adolescents.

When

Caroline Coon told Sniffin’ Glue’s editor Mark P about the Pistols, he thought

they were about dyed hair, and wasn’t interested. However, when he saw them

he couldn’t believe how arrogant they were, how exciting and powerful. Like

everyone else who saw the Pistols, he had to go off and form his own band. Of

course, the cyberwallflowers of the post-cyber Popsicle Academy are unimpressed

by such events. Apparently being excited by loud guitars is simply a recipe

for Britpop boy bands. In this regard, comparison between the rock texturation

of Oasis and the Pistols is illuminating. The Pistols are a diabolical piston,

an active reprimand to the Platonic discorporate Ideal, a sexuo-alchemical catalytic

converter, a dialectical-materialist physical heave-ho; Oasis are a blinkered

body, sullenly mired in a single inert power chord, unable to thrust either

harmonically or rhythmically. Noel Gallagher learned from Kurt Cobain how to

smother the collective dialectic of rock in a single individual's vocal suffering,

restoring interiority and emotion, expression as private property. Of course,

the industry prefers such music, it fits its ideology of possessive individualism,

where award ceremonies look more and more like stock-exchange reports. However,

as Marx said in The German Ideology, 'The difference between the individual

as a person and whatever is extraneous to them is not a conceptual difference,

but a historical fact.' [Marx, The German Ideology, Ed. Cit., p. 81]. Individualism

is not a style option, it is a stance vis-a-vis the struggle of classes. As

Johnny Rotten said, criticising music journalists: 'These writers have never

been in bands, and they have never really committeed themselves to other people

in such close quarters. They're more like solo performers, and there ain't no

such thing as that in any band ... I don't care how big-headed the lead singer

is, it all comes down to the fact that he must eat shit in a rehearsal room.

The histrionics of the lead guitar, the excesses of the drummer and the stupidity

of the bass player have to mix on an equal footing.' [John Lydon, Rotten: No

Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1993, pp. 159-160].

When

Caroline Coon told Sniffin’ Glue’s editor Mark P about the Pistols, he thought

they were about dyed hair, and wasn’t interested. However, when he saw them

he couldn’t believe how arrogant they were, how exciting and powerful. Like

everyone else who saw the Pistols, he had to go off and form his own band. Of

course, the cyberwallflowers of the post-cyber Popsicle Academy are unimpressed

by such events. Apparently being excited by loud guitars is simply a recipe

for Britpop boy bands. In this regard, comparison between the rock texturation

of Oasis and the Pistols is illuminating. The Pistols are a diabolical piston,

an active reprimand to the Platonic discorporate Ideal, a sexuo-alchemical catalytic

converter, a dialectical-materialist physical heave-ho; Oasis are a blinkered

body, sullenly mired in a single inert power chord, unable to thrust either

harmonically or rhythmically. Noel Gallagher learned from Kurt Cobain how to

smother the collective dialectic of rock in a single individual's vocal suffering,

restoring interiority and emotion, expression as private property. Of course,

the industry prefers such music, it fits its ideology of possessive individualism,

where award ceremonies look more and more like stock-exchange reports. However,

as Marx said in The German Ideology, 'The difference between the individual

as a person and whatever is extraneous to them is not a conceptual difference,

but a historical fact.' [Marx, The German Ideology, Ed. Cit., p. 81]. Individualism

is not a style option, it is a stance vis-a-vis the struggle of classes. As

Johnny Rotten said, criticising music journalists: 'These writers have never

been in bands, and they have never really committeed themselves to other people

in such close quarters. They're more like solo performers, and there ain't no

such thing as that in any band ... I don't care how big-headed the lead singer

is, it all comes down to the fact that he must eat shit in a rehearsal room.

The histrionics of the lead guitar, the excesses of the drummer and the stupidity

of the bass player have to mix on an equal footing.' [John Lydon, Rotten: No

Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1993, pp. 159-160].

When the

Pistols played in Cromer, they did not provoke chaos or offend their audience.

They played a sleek, strong, impressive set. Rotten relished every word of his

lyrics, Sid Vicious managed to keep time. Before

they came on, they played dub plates through the PA. Only the defiant proletarian

militancy of dub could be adequate to the Pistols’ power-chord rhetoric. The

ruin of the F-Club at Brannigans in Leeds was spelt out when the DJ played David

Bowie and Blondie after the bands: petitbourgeois aspiration and showy individualism

was built into the rightwing interpretation of Punk, and its connections to

fascism were not hard to discern. In Leeds, Rock

Against Racism was an aesthetic and political necessity.

The recuperation

of the rock power-chord by radio-friendly corporate rock acts has currently

reached an epitome of stupidity. Stewart Home's political critique of Punk requires

an injection of musical criticism. The rock power-chord needs to be criticised

immanently, from the inside, which means opening the ear to Derek Bailey's guitarism.

Derek Bailey's guitar freedom could only have been

developed by someone who rejects the narrow confines of the star system, by

someone who sees musical potential in every situation, unhampered by commercial

image and the requirements of investment capital. His investigation of the guitar

as material sound source produces a depthless music of sonic effect, a proletarian,

working-musicians's realism. Like punk, it denies romantic resonance or fraudulent

evocations of exotic terrains - the exchange-value basis of commodified music.

Like punk, the attempt to create stars out of its

protagonists undermines its power and logic. When punks followed The Damned's

saxophonist Lol Coxhill into the church halls and pub rooms of Free Improvisation,

the listener was introduced to a completely different but equally powerful criticism

of the commercial spectacle. Free Improvisation is music as listening use value,

as touchable humanity. (How Free Improvisation will deal with its own recuperations

and discontents - the respective lures of art money, yuppie ambient anaemia,

traditional-instrument classicism and installation-art postmodernism - is still

being worked out.) Just as the Lettrists and Situationists made Punk possible

by their invisible work in the 1950s - understanding graffiti and vandalism

as expressions of proletarian consciousness, unitary urbanism, the theory of

the Spectacle - the anti-idiomatic 'non-music'

of Free Improvisation will be crucial to criticism of musical commodification

in the coming epoch. Bailey's restructuring of guitar sound upsets identity-thinking

and denaturalises today's commonly-accepted 'sound of revolt'. It undermines

the assumption that musical experience hinges on the purchase of pre-recorded

sound. Free Improvisation is an eruption of naked use value in a system of prurient

exchange. This revolt against mass-musical duplicity and commodification will

resurface in the most unlikely circumstances, not least in the mass sphere itself.

It will use every aspect of disrespect for the commodity - every technical denial

of culture as a tissue of substitutions - which are currently being worked out

on the invisible margins. The brute facticity of

Blast and Punk and

Derek Bailey are part of an active continuum that cannot be understood using

non-revolutionary categories. You have been warned.

(B=Ben Watson;

E=Esther Leslie)

Get

You Back Home

B:

When formulating his ideas about money and capital - sketches for the great

work Capital which were eventually published under the name Grundrisse - Karl

Marx developed a critique of conventional ways of writing history. When people

relate history as a succession of events unfolding in time, they distort reality

by assuming that concepts that were actually the

product of historical developments were always in existence. He complained that

people project back concepts like human equality, money-making and commercial

calculation into the mists of time, when these are actually only possible once

there is an infrastructure of trade, roads and manufacture. If Punk

is approached retrospectively as a successful pop

phenomenon, a fashion wave, a raft of new celebrities, our understanding is

coloured by a similar kind

of back projection. Commercialised anger didn't exist before punk - rap would

have been impossible without it - and situationist ideas now accepted as commonplace

were inaccessible to anyone but intellectuals. At

the time, Punk felt like risk and truth, not scam, celebrity and money.

B:

When formulating his ideas about money and capital - sketches for the great

work Capital which were eventually published under the name Grundrisse - Karl

Marx developed a critique of conventional ways of writing history. When people

relate history as a succession of events unfolding in time, they distort reality

by assuming that concepts that were actually the

product of historical developments were always in existence. He complained that

people project back concepts like human equality, money-making and commercial

calculation into the mists of time, when these are actually only possible once

there is an infrastructure of trade, roads and manufacture. If Punk

is approached retrospectively as a successful pop

phenomenon, a fashion wave, a raft of new celebrities, our understanding is

coloured by a similar kind

of back projection. Commercialised anger didn't exist before punk - rap would

have been impossible without it - and situationist ideas now accepted as commonplace

were inaccessible to anyone but intellectuals. At

the time, Punk felt like risk and truth, not scam, celebrity and money.

In the

1950s the name Day-Glo was trademarked and in the late 1960s the company formally

changed its name from Switzer Bros Inc to Day-Glo Colour Corp. In their names

one can hear the poetry of science, industry and space exploration. The full

trademarked pigment set comprises Neon Red, Rocket Red,

Fire Orange, Blaze Orange, Arc Yellow, Saturn Yellow, Signal Green, Horizon

Blue, Aurora Pink, Corona Magenta, Strong Corona Magenta, Strong Saturn Yellow.

Day-Glo

first infiltrated the American landscape as entertainment then as an alert to

danger and later as commodity shriek. A fan of Ultraviolet light, who runs a

website dedicated to its discussion, writes of a trip to Disneyland in the Summer

of 1961. There he rode through psychedelic landscapes - such as the Alice

in Wonderland ride - made of Day-Glo

scenes extra-illuminated

under u.v. light. Day-Glo

fluorescent paint was

fairly easy to get hold of in the 1960s - it became a household word through

Tom Wolfe’s book on Ken Kesey and the Pranksters. It remained a bad taste product,

acceptable only to commercial art, where Psychedelia found a use for it in posters

and it found its way into film. In the entry on the word Day-Glo

the OED quotes an article

from the Listener, from 1968, which condemns the use of flashing Day-Glo

colours as vulgar signal

of an orgasm in a film by Jack Cardiff. The hippies used Day-Glo

in their cultural artefacts,

and even on their bodies, but theirs was an attempt to paint over the world

in the colours of their hallucinogenic trips. Day-Glo

was being taken into

the student bedroom, the kids’ blacklit den where individual mediation could

hinge on the wonders of a perceptual trick that disappeared when normal electricity

resumed.

In the

1950s the name Day-Glo was trademarked and in the late 1960s the company formally

changed its name from Switzer Bros Inc to Day-Glo Colour Corp. In their names

one can hear the poetry of science, industry and space exploration. The full

trademarked pigment set comprises Neon Red, Rocket Red,

Fire Orange, Blaze Orange, Arc Yellow, Saturn Yellow, Signal Green, Horizon

Blue, Aurora Pink, Corona Magenta, Strong Corona Magenta, Strong Saturn Yellow.

Day-Glo

first infiltrated the American landscape as entertainment then as an alert to

danger and later as commodity shriek. A fan of Ultraviolet light, who runs a

website dedicated to its discussion, writes of a trip to Disneyland in the Summer

of 1961. There he rode through psychedelic landscapes - such as the Alice

in Wonderland ride - made of Day-Glo

scenes extra-illuminated

under u.v. light. Day-Glo

fluorescent paint was

fairly easy to get hold of in the 1960s - it became a household word through

Tom Wolfe’s book on Ken Kesey and the Pranksters. It remained a bad taste product,

acceptable only to commercial art, where Psychedelia found a use for it in posters

and it found its way into film. In the entry on the word Day-Glo

the OED quotes an article

from the Listener, from 1968, which condemns the use of flashing Day-Glo

colours as vulgar signal

of an orgasm in a film by Jack Cardiff. The hippies used Day-Glo

in their cultural artefacts,

and even on their bodies, but theirs was an attempt to paint over the world

in the colours of their hallucinogenic trips. Day-Glo

was being taken into

the student bedroom, the kids’ blacklit den where individual mediation could

hinge on the wonders of a perceptual trick that disappeared when normal electricity

resumed. It

took punk to fully assimilate Day-Glo

without transforming

it - that is vulgarity and all - in fact because of its bargain-basement, eye-catching

impudence. Jamie Reid’s cover for Never Mind the Bollocks

modelled itself on a crude supermarket display. This was consumer society staring

itself in the face. Art, as ever, was behind the times when Peter Halley began

to use Day-Glo

paints in his abstractions

in the 1980s. Punk had already camouflaged itself in the colours of the antagonist.

It

took punk to fully assimilate Day-Glo

without transforming

it - that is vulgarity and all - in fact because of its bargain-basement, eye-catching

impudence. Jamie Reid’s cover for Never Mind the Bollocks

modelled itself on a crude supermarket display. This was consumer society staring

itself in the face. Art, as ever, was behind the times when Peter Halley began

to use Day-Glo

paints in his abstractions

in the 1980s. Punk had already camouflaged itself in the colours of the antagonist.

In

1914, a member of the Rebel Art Centre, Wyndham Lewis launched a Vorticist magazine.

Lewis’ Blast was supposed to be a celebration of the blast furnaces of

the industrialized Midlands and North. Blast also suggests a hygienic

gale from the North. The emblematic representation of the vortex on the first

pages of Blast is a figuration of a storm-cone with the apex up: a signal

used by coastguards to represent strong winds from the north. Blast lends

perhaps the visual and polemical aesthetic of the punk fanzines. Blast

– with its glorious outrageously luridly pink cover and heavy anonymous blockish

black typography and polemical rants – was just as shocking as the Sex Pistols

Never Mind the Bollocks LP cover.

In

1914, a member of the Rebel Art Centre, Wyndham Lewis launched a Vorticist magazine.

Lewis’ Blast was supposed to be a celebration of the blast furnaces of

the industrialized Midlands and North. Blast also suggests a hygienic

gale from the North. The emblematic representation of the vortex on the first

pages of Blast is a figuration of a storm-cone with the apex up: a signal

used by coastguards to represent strong winds from the north. Blast lends

perhaps the visual and polemical aesthetic of the punk fanzines. Blast

– with its glorious outrageously luridly pink cover and heavy anonymous blockish

black typography and polemical rants – was just as shocking as the Sex Pistols

Never Mind the Bollocks LP cover.

In Vorticist stylisation the denial of the human form is executed in a heightening

of the flat surface of the image, and in a paring down of the elements involved.

Lewis presents the human form like girders and industrial shapes. He writes:

THE ACTUAL HUMAN BODY BECOMES OF LESS IMPORTANCE EVERY DAY. It now literally

EXISTS much less. Lewis headed towards a sort of masculinized androgynousness.

Interiority is expelled like dust by a sharp gust of Blastish air.‘Never

trust a hippy’ cautioned a Jamie Reid poster in lurid yellow - its exhortation

was against nature.

It is irresistible. Lewis in ‘The London Group’ insisted on ‘LIFE not ‘Old Masters’

and the rejection of art which is dead with heavy woodness or stone, instead

- 'here flashing and eager flesh, shiny metal.' (Blast p77) Shiny metal,

chrome had paled as the 50s Americana dream was tarnished, but plastics were

the new flexible friend of global economies. Punk’s postwar version of Lewis’

material desideratum forwarded not the machinic society but the plastic consumer

society. Polystyrene again:

In Vorticist stylisation the denial of the human form is executed in a heightening

of the flat surface of the image, and in a paring down of the elements involved.

Lewis presents the human form like girders and industrial shapes. He writes:

THE ACTUAL HUMAN BODY BECOMES OF LESS IMPORTANCE EVERY DAY. It now literally

EXISTS much less. Lewis headed towards a sort of masculinized androgynousness.

Interiority is expelled like dust by a sharp gust of Blastish air.‘Never

trust a hippy’ cautioned a Jamie Reid poster in lurid yellow - its exhortation

was against nature.

It is irresistible. Lewis in ‘The London Group’ insisted on ‘LIFE not ‘Old Masters’

and the rejection of art which is dead with heavy woodness or stone, instead

- 'here flashing and eager flesh, shiny metal.' (Blast p77) Shiny metal,

chrome had paled as the 50s Americana dream was tarnished, but plastics were

the new flexible friend of global economies. Punk’s postwar version of Lewis’

material desideratum forwarded not the machinic society but the plastic consumer

society. Polystyrene again:

The

Day-Glo

coloured vinyl

punk record is not a black hole or empty meaning,

but a circular assertion of anti-nature, of synthetic actuality. The record,

which had been forgotten as item, as disc, is brought back into visibility,

by the coloured vinyl – of course in combination with the miniature artwork

of the picture cover. This should not be confused with later attempts to stimulate

collectability and sales with picture discs or limited editions. The coloured

disc hoped to detonate a mini-shock, at least a surprise as it was slipped from

the cover. The record stopped being natural, a hippy dream where the listener

gazes at beautiful people photographed against shrubs and trees, the hippy dream

of an unsullied life. Punk made pop music historical and artificial once more.

It devastated the romantic idyll.

The

Day-Glo

coloured vinyl

punk record is not a black hole or empty meaning,

but a circular assertion of anti-nature, of synthetic actuality. The record,

which had been forgotten as item, as disc, is brought back into visibility,

by the coloured vinyl – of course in combination with the miniature artwork

of the picture cover. This should not be confused with later attempts to stimulate

collectability and sales with picture discs or limited editions. The coloured

disc hoped to detonate a mini-shock, at least a surprise as it was slipped from

the cover. The record stopped being natural, a hippy dream where the listener

gazes at beautiful people photographed against shrubs and trees, the hippy dream

of an unsullied life. Punk made pop music historical and artificial once more.

It devastated the romantic idyll.

When

Caroline Coon told Sniffin’ Glue’s editor Mark P about the Pistols, he thought

they were about dyed hair, and wasn’t interested. However, when he saw them

he couldn’t believe how arrogant they were, how exciting and powerful. Like

everyone else who saw the Pistols, he had to go off and form his own band. Of

course, the cyberwallflowers of the post-cyber Popsicle Academy are unimpressed

by such events. Apparently being excited by loud guitars is simply a recipe

for Britpop boy bands. In this regard, comparison between the rock texturation

of Oasis and the Pistols is illuminating. The Pistols are a diabolical piston,

an active reprimand to the Platonic discorporate Ideal, a sexuo-alchemical catalytic

converter, a dialectical-materialist physical heave-ho; Oasis are a blinkered

body, sullenly mired in a single inert power chord, unable to thrust either

harmonically or rhythmically. Noel Gallagher learned from Kurt Cobain how to

smother the collective dialectic of rock in a single individual's vocal suffering,

restoring interiority and emotion, expression as private property. Of course,

the industry prefers such music, it fits its ideology of possessive individualism,

where award ceremonies look more and more like stock-exchange reports. However,

as Marx said in The German Ideology, 'The difference between the individual

as a person and whatever is extraneous to them is not a conceptual difference,

but a historical fact.' [Marx, The German Ideology, Ed. Cit., p. 81]. Individualism

is not a style option, it is a stance vis-a-vis the struggle of classes. As

Johnny Rotten said, criticising music journalists: 'These writers have never

been in bands, and they have never really committeed themselves to other people

in such close quarters. They're more like solo performers, and there ain't no

such thing as that in any band ... I don't care how big-headed the lead singer

is, it all comes down to the fact that he must eat shit in a rehearsal room.

The histrionics of the lead guitar, the excesses of the drummer and the stupidity

of the bass player have to mix on an equal footing.' [John Lydon, Rotten: No

Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1993, pp. 159-160].

When

Caroline Coon told Sniffin’ Glue’s editor Mark P about the Pistols, he thought

they were about dyed hair, and wasn’t interested. However, when he saw them

he couldn’t believe how arrogant they were, how exciting and powerful. Like

everyone else who saw the Pistols, he had to go off and form his own band. Of

course, the cyberwallflowers of the post-cyber Popsicle Academy are unimpressed

by such events. Apparently being excited by loud guitars is simply a recipe

for Britpop boy bands. In this regard, comparison between the rock texturation

of Oasis and the Pistols is illuminating. The Pistols are a diabolical piston,

an active reprimand to the Platonic discorporate Ideal, a sexuo-alchemical catalytic

converter, a dialectical-materialist physical heave-ho; Oasis are a blinkered

body, sullenly mired in a single inert power chord, unable to thrust either

harmonically or rhythmically. Noel Gallagher learned from Kurt Cobain how to

smother the collective dialectic of rock in a single individual's vocal suffering,

restoring interiority and emotion, expression as private property. Of course,

the industry prefers such music, it fits its ideology of possessive individualism,

where award ceremonies look more and more like stock-exchange reports. However,

as Marx said in The German Ideology, 'The difference between the individual

as a person and whatever is extraneous to them is not a conceptual difference,

but a historical fact.' [Marx, The German Ideology, Ed. Cit., p. 81]. Individualism

is not a style option, it is a stance vis-a-vis the struggle of classes. As

Johnny Rotten said, criticising music journalists: 'These writers have never

been in bands, and they have never really committeed themselves to other people

in such close quarters. They're more like solo performers, and there ain't no

such thing as that in any band ... I don't care how big-headed the lead singer

is, it all comes down to the fact that he must eat shit in a rehearsal room.

The histrionics of the lead guitar, the excesses of the drummer and the stupidity

of the bass player have to mix on an equal footing.' [John Lydon, Rotten: No

Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1993, pp. 159-160].