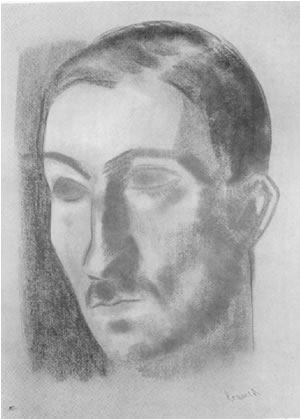

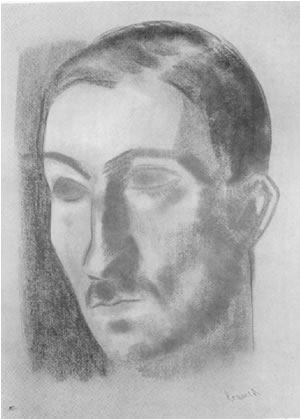

Head Study (Charles Lahr) by Jakob Kramer from New Coterie 6

2. NEW COTERIES

As my mother labours to bring forth one insignificant human being, her struggles are mirrored daily by thousands of craftsmen and labourers who, with much dirt, debris, bang and clatter, are acting as midwives to the rebirth of the City, which is to deliver in ten years more than 250,000 new buildings. a re-creation of the environment referred to in the press as ‘an unprecedented building boom’ for the new is replacing the old with ‘bigger and more modern structures’ while remodelled roads are concretizing into ever widening channels. But each building as it rises, or falls, casts a shadow of what has gone before and what is yet to come, so that even more ‘modern’ buildings can be seen waiting impatiently in the wings. Around them the shadow of motorways, the hedgerows and fields of former centuries reflected in the macadam to join with the flora and fauna of the bomb sites when the frenetic dance of urban demolition is given a starring role. Above it all hangs a nuclear mushroom.

Compared to all this the result of my mother’s efforts is puny, but I am the first child ever to be born, so my parents convey me home to their flat in Rosebery Avenue, Finsbury, opposite to which with much dust and noise the 16th century Thomas Sadler’s Musick House is exiting to allow Sadler’s Wells theatre to make its appearance. a debut which inspires my mother, as she nurses me in her arms, to dream for me the future denied her: A future as a dancer, a great ballet dancer, a great singer, a great musician, a great actress, a great writer..... But, as she muses, the wreckers move in and the disintegrating flat moves off stage.

Thereafter, we take all that we own and make our way to a house in Fairbridge Road, Holloway, for our exodus from the inner city is to be gradual. It should be noted here that while my mother is taking possession of the downstairs flat of the house, assisting my father to lay lino (which he does in a hurry and without proper measurement) arranging furniture in rooms for which it was not bought, wiping down woodwork, hanging curtains and generally making order out of chaos, Vienna is rocked by revolutionary demonstrations and Germany, in which the salutation ‘Heil Hitler’ is now common, demands the annexation of Austria. In America, Sacco shouts ‘Long Live Anarchy’ as he and Vanzetti go to the electric chair.

But these events pass my mother by at a distance, for her greatest concern, apart from myself, is the demise of THE NEW COTERIE - A Quarterly Magazine of Art and Literature published at three-monthly intervals between November 1925 and Summer/Autumn 1927, under her adopted maiden name of Archer. This magazine a revival of an enormously influential, but short-lived, magazine published by Frank Henderson at his left-wing bookshop and which my parents hope will bring them recognition, for they are to publish such writers as D.H. Lawrence, H.E. Bates, Rhys Davies, Liam O’Flaherty, Aldous Huxley, T.F. Powys, Louis Golding, Geoffrey West, Faith Compton Mackenzie, T.F. Powys, Louis Golding, Geoffrey West, Faith Compton Mackenzie, Michael Joseph, Jean Devanny.... Therefore, my advent has corresponded with the dashing of their hopes for fame, if not fortune. It is as if my procreation and birth have drained from them all creative energy leaving them squeezed and dry.

Head Study (Charles Lahr)

by Jakob Kramer from New Coterie 6

At 9 Wilton Road I grow up with the characters of THE NEW COTERIE, piled in their dwellings around me, as if they are part of our extended family. Now, I have one set only, given to me by my mother as if she were handing on to me my inheritance. And, as I grow older, travelling backwards to meet my parents on the mound, these characters, caught up in their time capsules, remain as they ever were, cocking a snook at their disintegrated progenitors.

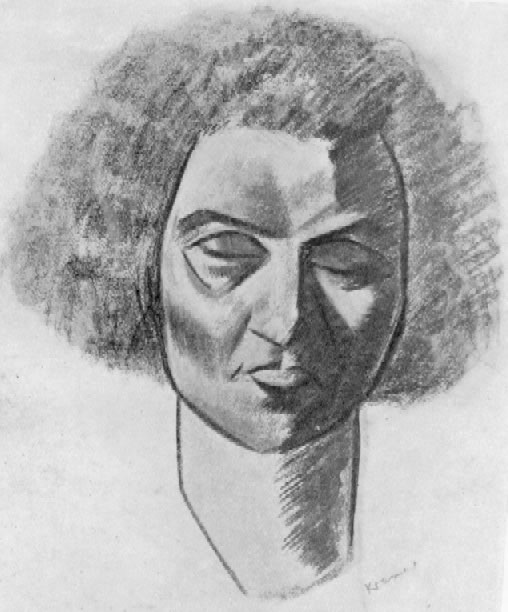

Esther by Jacob Kramer from

New Coterie 2

The mother-fixated man from No. 6, again and again walks the country lane on his way home after years abroad. His thoughts filled by love for his mother and hate for the girl by whom he was jilted many years before. His anger conjures up the girl and she stands before him invitingly on the path. In a sexual frenzy he carries the now willing woman into the woods where they couple. Of course, the woman is not the ‘lost love’, but is the man’s widowed mother out for what Erica Jong in FEAR OF FLYING called ‘a zipless fuck’, and the women knows that we know and lives out her shame until the paper crumbles, but her son, this 20th century Oedipus again and again leaves home and returns abroad unaware that he has once more violated his mother. (3)

In No. 4 the blonde Mrs. Salgast lies in childbed, dismayed because she has given birth to a Maori baby while her husband is white and supposedly of English heritage. Down the road in this New Zealand mining town her racist husband rages at the local Maori who laughs loud and long before revealing that the outraged husband is half Maori, but adopted by English parents. (4)

The jaded housewife from No. 4 is on holiday in Spain where she flirts with the elements to indulge in a sensual affair with the sun. "I am another being" she says to herself as she looks at her red-gold breasts and thighs. (5)

In Deauville, the middle-aged, middle-class spinster from No. 5 sits at the side of a dance floor. She is waiting vainly to be asked to dance. The author, in an estimation of this plain creature, has named her ‘Miss Drone’: Barren, sex-starved, surplus. Intolerant of her own creation, the author does not see Miss Drone’s brave smile as the couples swing past and the music blares out its cheerful tunes. She is blind to Miss Drone’s tremulous smile of pretence that she has chosen to be a wallflower. Instead, the author smirks in malicious glee as the plot develops and a young man, a little the worse for drink, asks Miss Drone to see him to his hotel room. In some trepidation she agrees and accepts his invitation to stay the night. Now the author laughs out loud. She has got Miss Drone where she wants her, for the ‘young man’ is discovered to be a young woman in male clothing. The author, finished with her story, mails it to THE NEW COTERIE, and remains unaware that Miss Drone has escaped her and set up home with her new-found friend, the two of them living happily together as a couple. (6)

At another time and place, two young men from No. 1, Republicans, crouch on a roof somewhere in Ireland, pistols in hand, waiting for death meted out already to their companions by British soldiers. The younger man, an IRA Lieutenant, white-faced, closes his eyes, hoping to shut out the scene and imagine himself some place else. His companion, the Quarter-Master, despises his companion and swears that he will shoot him at the first sign of surrender. At long last a shot rings out and the Quarter-Master falls forward as the British climb over the roof. With a sigh of relief, the Lieutenant pulls himself to his feet, hands over head in surrender. "Let’s give it to the bastard" says one of the soldiers and they fire point-blank into his head. (7)

Unaware of the Civil War being played out around him, the senile old man in No. 4 opens the canary’s cage and urges it to fly away for no more can he bear to hear it sing. (8)

Muriel from No. 6 sits in a cafe opposite a woman friend who talks continually about nothing, her empty voice falling into the space between them. Muriel, only half listening, concentrates her thoughts upon the lampshades: "Great yellow lampshades, floating...spreading a warm glow...hazy and warm.... (9)

In No. 3 a man lies dying, his thoughts wandering: "He imagines a murderer coming out of his cell to take those few steps to the hangman’s shed...He thinks of the homeless searching about for shelter, warmth, food...His mind wanders farther afield and he pictures his wife about to give birth...he imagines a man in the throes of torture...boiling oil...the rack...castration...he thinks of a harem with beautiful scented maidens.... (10)

The Editor, whom I suspect was Paul Selver, the translator of the first published The Good Soldier Schweik by Jaroslav Hasek, decrees that all these characters must live out their lives, if not conventionally, in conventional forms, within the confines of classical literature. For this deity, fastidious in his selection of material for the magazine, eschews the writers experimental in form, disapproving of Jean Cocteau and dubbing the Imagists ‘Our impetuous young friends’. On hearing that James Joyce has been translated into French, he asks "But who is going to translate him into English?"

And yet, in spite of all the editor’s efforts, newspapers which published reviews of the magazine, complain:

"The latest exponent of that somewhat curious class of wielders of the pen and pencil which the modern age has produced, who, we believe, are known (or call themselves) Impressionists, Realists, Decadents, or what not; very young men who view life through distorted, cracked and muddy spectacles and confusedly imagine that ‘Literature’ should be spelled ‘Muckraking’!"

The Editor, taken up by these polemics, his head bent over pen and paper, does not hear the doctor’s experiments with sound in No. 2 (11), nor does he see the black and white illustrations or hear the singing poetry. Sidney Hunt’s machine-like Beauty Chorus pass him by as they dance off stage, hidden behind them Liam O’Flaherty’s fratricide from No. 3. Bent over his desk he misses Coralie Hobson’s partying group as they pass by Jean de Bosschere’s frontispiece to No. 2, laughing uneasily at the two men (or is one of them a woman?), hanging from gibbets and engaging each other in sword play. Nor does he hear the priest reading prayers, while an angel weeps.

This Editor is blind also to Richard Wyndham’s lines of washing in No. 2, counterpanes, curtains, sheets and a single dark dress, blow and billow in the wind, hanging at various levels so as to almost obscure houses and the potted plants on window-sills. That black dress must surely belong to Miss Morgan from No. 2 who will wear it at her authoritarian father’s funeral. There she stands, before the open grave, counting out the inherited wealth which will buy her a husband. (12)

Willy nilly these characters, among others, live out their lives in the pages of THE NEW COTERIE (Cover designed by William Roberts).

At 9 Wilton Road, piled up bundles of unsold NEW COTERIES , in the press room, or stacked on bookshelves, form a constant reminder to my parents of their lost hopes and a rebuke to me for my supersedence. Sometimes, I take a copy from a shelf and having prevailed upon my father to cut the pages to set the characters free, I enter into their lives which become inextricably intertwined with mine. But it is only recently that I have perused each issue intently from cover to cover, reading carefully each Editorial, story, poem, both original and in translation. I have looked at, and fantasized over, the art-work. This in an endeavour to find the key to my parents’ and my own lives.

My father, having bought William Morris’ old press, the Blue Moon press had also been launched by my parents - given its name because the intention was to publish occasionally and selectively fine, limited editions. This took up a room in our house and was manipulated by a printer named Herbert Jones. Outside the Progressive Bookshop, 68/69 Red Lion Street, Holborn, a crescent moon painted blue hung upon a chain from a wall bracket. With what pride my father climbs up the ladder, precariously perched against the wall, to hang this symbol, while my mother watches from the street, instructing him to move the angle-iron this way, or that. Henceforth they would be recognised not only as booksellers, but as publishers.

All this at the beginning of a recession which bounded across the Atlantic, to bounce the Rt. Hon. Ramsay MacDonald M.P., tossing his fine mane of white hair, into mixed metaphors by naming an ‘economic lifeboat crew’ of Government Ministers to save the country as it ‘lurches over the precipice’! He rejects the solution of pump priming the economy offered by Maynard Keynes.

On Wall Street the police disperse hysterical crowds howling against the plummeting of their stocks. In Berlin, the Nazis are out on the street, standing on street corners like an invading and avenging army, intent upon beating up Jews and ‘reds’. My mother is fearful. Pogroms threaten, Slump and depression. The world is out of kilter.

In Palestine, British troops intervene with fire-power between fighting Jews and Arabs. In Russia, Stalin declares all farms as Collectives: "So began the strange Carnival over which despair presided and over which fury filled the fleshpots." (13)

The bookshop and the Blue Moon press limp on, but the press produces less and less ass the years progress, until only the occasional leaflet, or card of poetry, is published ‘once in a blue moon’. It is as well that the blue metal moon to hang so proudly until a bomb destroys the bookshop during the Blitz of the Second World War, was decrescendo. And in this case the moon did not lie.

Most of the first two years of my life are to be spent in Fairbridge Road, to which we had moved from Rosebery Avenue. This Road lying between Hornsey and Holloway Roads, Islington. It had been formed in 1878 by a short street of isolated cottages near to Hornsey Road. The type of area seen as ripe for development. By 1882 builders, encouraged by the expansion of the railway network, had quickly erected pristine, red-brick Victorian terrace houses, complete with bay windows or sash windows, which they then decorated with mock Corinthian columns. Incorporating, as they built, the former Esher Road. Once the road was laid and all signs of flourishing nature subdued, in moved the Pooters, the Cummings and the Gowings (14) together with their wives, children and maidservants, to live hedged in by heavy furnishings, multiple ornaments of china shepherdesses, rose baskets, and golden-framed reproductions of ‘The Stag at Bay’ or ‘Virtue Rewarded’.

As it happens, at No. 155 for four years from 1904 lived Samuel Lazarby of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants. For this was truly ‘the age of the train’. How self-importantly he leaves the house each morning dressed in clean white shirt, stiff collar, dark suit, fob watch, high hat and carrying an attache case and rolled black umbrella. His wife and maidservant watching his progress from the front doorway. The self-absorbed Samuel Lazarby, walking tall, fails to look about him. If he had done so, he might have spied the slightly less affluent houses of the 1920s and 1930s, let out as flats. Many of these with open doorways through which children spill onto the street, to shout and laugh as they skip, stringing a rope across the road, , or chasing each other back and forth across the road in a game of ‘it’, or dodging behind garden walls and dustbins in a game of hide-and-seek, or in so many other games known only to children. Does he feel their unseen eyes as he crosses the hop-scotch grids to be chalked on the pavements, or is he instead frightened by the deathly silence descending in the 1940s when the children have been sent out of London to escape the bombing. An unnatural silence broken by sirens, bombs whining down and exploding, the fire of anti-aircraft guns. And, at the same time, does he uneasily feel the presence of parked cars which are to eventually de-grade his members?

Nowadays, Fairbridge Road is much as when first built, apart from its environment of motor traffic and stationary vehicles. The net-curtained houses, most of them owner-occupied in recent times, present a quiet front to the world. Only the Hornsey Road end, the original Fairbridge Road, has been obliterated by a wood yard which spills its planks onto the pavement, next to which is a transport firm from which trucks send out noise, fumes and danger to pedestrians. Both activities presenting a general air of dirt and disorder. At this end has also been built large blocks of low rise Council flats. It is as if the former Esher Road is intent upon obliterating all evidence of its usurpation. Because of these industrial activities and the proximity of the busy Hornsey Road with its small ethnic shops and cosmopolitan population, it is unlikely that Fairbridge Road will regain its original gentrification, for the professional classes prefer to be cocooned in their classical Georgian Squares away from the hustle and bustle of urban street life.

Perhaps, in 1929, the signs of the inner city throwing out its tentacles to grasp this part of North London, decide my parents to move on to Muswell Hill, but for the short time we live in Fairbridge Road our family becomes extended by my father’s sister Tante Maria and Margot, the illegitimate daughter of my mother’s friend Dornan. Margot, a child some five years older than me.

"Why don’t you bring Maria over to England? suggests my Aunt Mary (christened Anna Maria) to my father. My Aunt Mary lives and works at a West London hotel and today is her ‘day off’, so she has visited my father, her brother, at the bookshop. "She’d be glad to come over to mind the baby while Esther works in the shop." The expression on my father’s face is doubtful, for his sister Maria is barely known to him and when they met briefly, during his visit to the Rhineland in 1927, he found almost nothing to say to her. "Esther would never agree" he mutters. "Esther would prefer to be at the shop" my Aunt wheedles. "She’ll soon get bored at home, you haven’t married a domesticated woman. Maria would take better care of the baby." My father looks worried, but he doesn’t refuse the suggestion outright, and my Aunt comes in for the kill.

"You remember how Maria and the others were worked half to death and half-starved by Fritz, our dear brother! After Mother and Father had died and he took Hof Iben?" This was guaranteed to encourage in my father a feeling of guilt at being so far away when both parents died, one after the other, his mother, Barbara geb. Schlamp in 1909, worn out with bearing fourteen children of whom my father was the eldest, and his father, Philipp in 1911, worn down by sowing and reaping. As my father, his brother Heinrich (called by us ‘Henry’) and Aunt Mary were in England, only Fritz was adult enough and on the spot to run the farm. My Uncle Fritz, determining to make the farm pay, worked his younger brothers and sisters mercilessly and fed them little. The nearby villages buzzed with the scandal and within a short time a family meeting was called by the Aunts and Uncles, to reach an agreement upon apportioning the children among them. Then, they climbed the steep hill to Hof Iben and descended upon the fields like an avenging army, to wrest this cold and hungry store of cheap labour from the grasp of the sullen, yet frightened, Fritz.

"Fritz was punished, of course" says my Aunt with satisfaction, as she views Fritz’s crushed body beneath the hoofs of the horses. "But not before he had cheated us out of our share of Hof Iben and left it to that useless wife of his!"

My father goes home to Fairbridge Road. "Mary says my sister Maria would be willing to come over here and take care of the baby, while you’re in the shop" my father tells my mother, carelessly, as if he is not pushing the matter. My mother’s first reaction is to say no, but marooned within the flat with a small baby while my father is experiencing ‘true living’, has begun to get take its toll. She wants to take care of me, her first live child, and yet, and yet, and yet... She has no affection for my Aunt Mary, whom she sees as over-bearing and malicious, and suspects that Maria will be a second edition of Mary, and yet, and yet, and yet... My father will not let the matter alone. He cannot manage in the shop. He has to close when he goes round the secondhand bookstalls and the publishers. My mother knows what this means - loss of custom and, therefore, money and loss of passing trade, which also spells money. His sister Maria is a peasant woman, an earth mother, my father tells my mother, she knows about babies, knows more than does my mother. Unlike my mother, Maria wants nothing more out of life than Kinder und Küche.

But, it is my mother’s friend, Dornan, who solves for my mother her dilemma between baby and shop so that she agrees to let my Tante into the house. This comes about because Dornan’s fostering arrangements for her child at a private residential nursery have broken down. "She’s not happy there" says Dornan "it’s all terribly hygienic, but no stimulation. You and Charlie would be good for her and while your sister-in-law’s caring for one child, she might as well care for two. We’ll fix terms."

And so my Tante arrives to live with us, an early version of an au pair, trailing in her wake the strawberries which several years later would become her life’s work in Odenwald. Strawberries, in German, ‘Die Erdbeeren’ - the earth berries: Truly, my Tante is to become an ‘earth mother’!

"A real Truby King baby...(is) fed four-hourly from birth...and they do not have any night feeds. A Truby King baby has as much fresh air and sunshine as possible and the right mount of sleep. His education begins from the very first week, good habits being established which remain all his life..." From DREAM BABIES: CHILD CARE FROM LOCKE TO SPOCK: By Christina Haydyment: pubd. Jonathan Cape 1983.

Truby King, one time superintendent of the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum at Dunedin, New Zealand, was at that time the writer of fashionable baby books. He ordained that baby be ‘fed by the clock’. "Mothers become absurdly distressed by the sound of a mere hour or so of crying. The great value of a trained nurse was that she could override all maternal objections and make sure that the baby was kept on a routine until it despaired of anything better" said Truby King and he was sure that if only men were able to secrete milk, they would make much better parents than "sentimental mothers".

Christine Haydyment writes in DREAM BABIES: The war-time habits of obedience to authority extended into the shaky years of peace that followed. Depression reinforced the need for firm leadership and the build-up to the second world war...left parents as resigned to following bulletins of approved infant-care practice as they were to coping with ration books. In England infant welfare legislation in 1918 set up centres for parents to learn the newest methods of child-care. In America the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921 played a similar role.

But even my politicized mother did not understand this manipulation of society and accepted that ‘educated’ mothers brought up their children according to the latest ideas - for after all, it was ‘in the book’.

Of course, to my Tante, such a regime for a baby is as much gobbledegook as the noises coming out of the mouths of the persons around her, for she knows no English. As strange to her as the miles of terrace houses lining long hard roads and the thought of being surrounded in London by eight million strangers. Coming from a peasant community where the rhythm of life is geared to work in the fields and the women not given to reading baby books, how could my Tante know that I, together with my contemporaries, am being trained for life in an industrial society, from cradle to grave, for the cold inexorable demands of the machine and the callousness of war. However, she shrugs and says to herself, if this is the English way, she will go along with it.

She is introduced to Margot. "Whose child is that?" and listens with scepticism to my mother’s explanation. "Schnell, schnell Margot (with a hard ‘t’) kommt wasch die Hände." A quick wipe with a flannel. "Schnell, schnell, schnell, Shul." My Tante rushing the pram up the road, me dumped inside it and Margot hanging on to its side.

Or, Ba-by hungry" Margot pointing to her own mouth. "Baby cry-ing", Margot wailing in imitation of my cry. "Draussen!" The back door opens and with a sharp thrust Margot is pushed outside. My Tante instinctively in this urban environment carrying out the prescriptive regime of Watson the Behavourist whose baby books were also fashionable and who saw mother love as ruining a child’s character:

"Put the child out in the backyard a large part of the time...away from your watchful eye..." DREAM BABIES.

I am fed, changed, fed changed, fed changed...sometimes the bottle propped up in the pram where I search for it with my mouth. But while the housework and the children pose no problem for my Tante, it is the isolation which she hates.

Sunday is my parents’ day for receiving visitors and for the first two Sundays my young Tante dons her best dress and carefully combs out her brown hair from its usual bun. But after one or two such Sundays she can see that this company is no good to her. Mouths opening and shutting in argument, gesticulation, voices growing louder cutting across one another, "Was ist los?" asks my Tante in consternation. "Politisch, politisch" explains my mother, and my Tante sneers. Politicians! The very people who have sold out the German people and left them to starve! What care she about the Tory government’s Trades Dispute Act, or the murder of trade unionists and Communists by Chiang Kai Shek, or the expulsion of Trotsky and Zinoviev from the Soviet Communist Party? Not even street fighting between Nazis and Communists in Berlin interests my Tante for she has never been there:

"Du bist verrückt mein Kind,

Du musst nach Berlin...." (15)

says a popular song. As for my Tante, she has enough to contend with, coping each day in this foreign City with her equally foreign brother and sister-in-law.

My father introduces her to writers who come to the house - Rhys Davies, John Arrow, James Hanley, Liam O’Flaherty, Malachi Whittaker, Gay Taylor and the artists William Roberts and Jacob Kramer. Sarah Roberts comes also for she is the wife of William and the sister of Jacob. But my Tante reads nothing apart from romantic magazines which she calls ‘books’ and Roberts she regards as a poor painter. His machine-like men don’t look like proper people and even his portrait of my mother makes her look gaunt and miserable. She likes pictures of pretty country scenes, landscapes, dream places where it would be pleasant to stay.

The highlights of my Tante’s stay in England are her visits to my Aunt Mary. Days which to her are a coming home. She counts up the time between them, hoarding scraps of news from their sisters’ letters, or from my parents’ lives. With her sister Mary, all day she is able to sit in the hotel kitchen eating, drinking coffee and gossiping. Of course, my Aunt Mary relates to my Tante what she knows of my father’s past life and my mother’s antecedents. And what she doesn’t know, she assumes.

My mother had been a member of the British Socialist Party, which following the Russian Revolution, dissolved itself into the newly formed Communist Party of Great Britain. My father had always considered himself an Anarchist, anarchism originally having been part of the Communist movement. However, both of my parents were distressed at the shooting down of the rebellious sailors at Kronstadt and although they remained at that time within the Communist Party, they became more and more uneasy as Stalinism took hold. This unease bringing in its train cynicism was to lead to my father’s expulsion from the Party. It happened like this. He had hung in the bookshop an abstract painting depicting various shapes and colours, which attracted attention from customers who asked:

"What’s that supposed to be, Charlie?" "That’s the comrades at the barricades - all six of them!" my father replied.

This was reported to my father’s Party branch and he was expelled for ‘levity’. My mother resigning from the Party in disgust. Later, a rumour was circulated that my father was a police spy and Henry Sara, who was to later found the Balham Trotskyist group, told my parents many years later that he had been instructed to stand around in the bookshop and report back to the Party my father’s conversations.

Now, my Aunt Mary spoke of my parents as ‘reds’ and Bloomsburyites, making it all sound a little shabby.

My Aunt speaks bitterly also of the man she had met on arrival in England at the age of eighteen. Frederick Eugene Stone, twenty years older than she, had made her pregnant with Edwin (known as ‘Ted’). They had married, but he had deserted them shortly after Cecil’s birth in 1916, and died of tuberculosis in 1926.

"I’d divorced him by then" complains my Aunt, "so there was no pension. No more use to me dead than alive!"

My Aunt, shortly before I was born, had written a story for a Daily Express 1927 St. Valentine’s Day competition, under the name of Marion Young, for which she won a prize of £5.00. This, she was sure, had made her my parents’ literary equal and she longed for their recognition. She was unaware that my father, proud of any literary success within the family, had saved the newspaper in which the story appeared. Many years later, and shortly before my father’s death in 1971, and in spite of the intervening years during which my parents had refused all traffic with my Aunt, my father gave this story to me for safe-keeping. My Aunt writes:

"The Spring of 1918 found me living in a third-rate lodging-house in Soho. The entrance to it was in a dismal court, and I rented the attic on the top floor back.

Being a widow with two small boys to support, I could not study my own comfort and although I hated bare boards, the slanting walls, and the view it gave me of half of the chimney-pots in London, I also appreciated its advantages. It enabled me to walk to my work in a West End restaurant and, considering it was harvest-time for greedy landladies, it was cheap.

Reaching home one night, I found a telegram to say my eldest boy, Sonny, was very ill. The tubes were closed and the omnibuses had ceased running, so I walked the eight miles to my baby. The doctor advised me to nurse him myself if I wanted him to get better. But the foster-mother, feeling herself slighted, told me I could take my boy to my own place as soon as I liked.

So, I wrapped him in a blanket and took him to my attic. There I fought for his precious life throughout long days and longer nights. To make things worse, my landlady, the only person I knew in the house refused to help me in any way. She said that I ought to have asked her permission to bring my child there, and how was she to know that Sonny’s complaint was not catching?"

This story entitled IMPOSSIBLE LOVE above a by-line HAD HE BEEN A WHITE MAN I SHOULD HAVE BEEN PROUD TO BECOME HIS WIFE goes on to tell of how my Aunt considers suicide "For one wild moment I thought of taking Sonny and myself to find rest in the dark waters of the Thames. The same instant, the happy face of my little Jim seemed to look at me through the gloom of the attic. I had nearly forgotten him in the stress of the last few days..." But then my Aunt is befriended by a Chinese lodger in the house who sits with Sonny while she goes out on errands, and provides her with good food for the child:

"At last I got back, and tearing up the stairs two at a time, I could hear my boy laughing merrily..."You wait Uncle Chong, till I am well again. You just show me the boy who peppered your face with a pea-shooter; I’ll fight him for you..."

Later, my Aunt having walked along the street with Chong to receive nasty looks and exclamations of "abominable, disgusting" decides that she cannot marry him. "He wanted to know if I would have accepted him had he been a white man, and I answered truthfully that I would have been proud to be his wife..."

On to Moving