6pm Saturday 22-iii-2014

address to the Arf! Arf! Arf! Zappa Weekend at Singel, Antwerp

Preamble: Max Kaiser & Bishop Brown

People ask me about music today, asking if anything tweezes my mind like Zappa. Generally I reply by recommending something which isn't music at all, in fact it's a financial advice show, because the host's rants have a similar effect on me to Frank Zappa's music when I first heard it in the early-70s. So I'm dedicating this talk to Max Kaiser, along with his fiancée Stacy Herbert, presenters of The Truth About Markets on Resonance Radio (the couple also present The Max Kaiser Show on the satellite-TV station Russia Today). Max and Stacey carry on the Great American Counter-Project which Zappa contributed to so richly, i.e. to dig out The Truth from the mountains of balderdash, boloney and bullshit foisted on us on a daily basis by the commercial media — and dig out this Truth in a manner regular folk can understand. In his comedy routines, Max Kaiser uses a realistic appraisal of the drives and proclivities of the human animal (with a particular emphasis on male interest in the opposite sex), to blow up the petty moralism and unthinking pieties used by the establishment to bamboozle and intimidate us. I imagine Zappa fans will enjoy Max Kaiser, so — even if (like me) you have no need of financial advice — I recommend him to you. And here's another American who may interest you as well. His name is Bishop William Montgomery Brown.

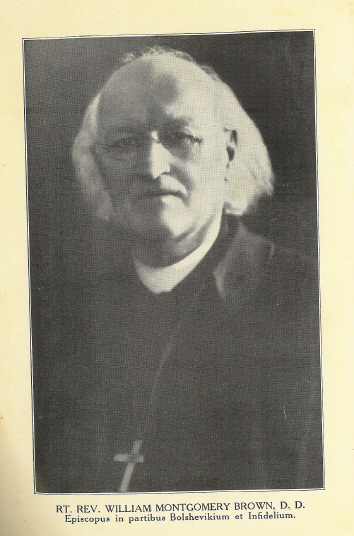

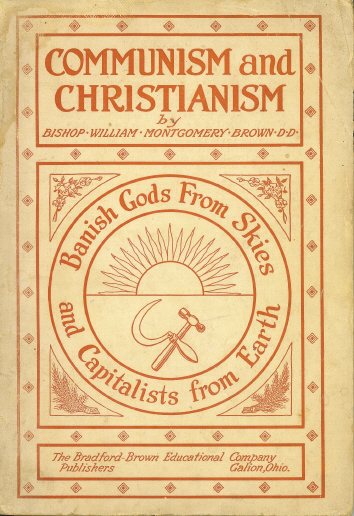

No-one talks much about Bishop Brown any more, the "Red Bishop" of Galion, Ohio, but his pamphlet — Communism and Christianism Analyzed and Contrasted from the Marxian and Darwinian Points of View — published from 1922 to the bishop's death in 1937, was an outstanding attack on Christianity in favour of a realistic appraisal of the drives and proclivities of the human animal. Below the author photograph in his book, he provides his own title, in Latin of course: "Episcopus in partibus Bolshevikium et Infidelium".

There are many reasons to regret Frank Zappa's early death. One of them is that I never had a chance to read quotes from Communism and Christianism, because I think they would've made Frank smile. It might even have changed his mind about Communism, and made him think more like Jimmy Carl Black, who when he saw me carrying a plastic bag from the left bookshop Bookmarx said, "You know us Indians had that idea first …", something I later found out was true by reading the Chicago surrealist Franklin Rosemont on Karl Marx's researches into the Iroquois. Bishop Brown has that quality which Matt Groening brought to The Simpsons and Max Kaiser brings to his financial advice: knowing that demolishing balderdash, boloney and bullshit is actually grade A entertainment.

In 1922, five years after the Revolution in Russia, Bishop Brown of the Protestant Church of America announced he'd been preaching lies and rubbish for the previous forty years. Henceforth, he was going to preach the Materialist Gospel according to Charles Darwin and Karl Marx — evolution and revolution — so that, instead of dreaming about the afterlife, people might build heaven on earth here and now. Bishop Brown sees Gods in the skies as a radical alienation of the human essence, which is in actual fact the culmination of aeons of natural history and centuries of human history.

Most liberal discussion of politics assumes that human beings are rational creatures governed by self-interest. Like Zappa and Kaiser after him, Bishop Brown will have none of this. "It has become apparent that intellectual conclusions do not dominate life. Life is determined by loves and hates." Then Brown goes on to say something which reminds me of Zappa's reference to intellectuals as "dead people" in the Warning/Guarantee at the start of his book Them Or Us: "Passion without intelligence may get us into trouble, but intelligence without passion gets us nowhere at all." (Communism and Christianism pp. 176-177). And, again like Zappa, Brown sees the free development of the individual as the moral task given each one of us, unconstrained by ideologies, leaders or trust in higher authority: "No man can live the moral part of his psychical (soul) life on the truth of another any more than he can live his physical (body) life on the meals of another. Every one must have his own truths, even as he must have his own meals." (Communism and Christianism pp. 46-47)

For Bishop Brown, this means that we are all in fact Gods; to worship Gods who are not ourselves is to suffer oppression and exploitation. Here's how he argues it, quoting the poet Omar Khayyam:

When I commenced my present ministry in the study,

I sent my Soul through the Invisible,

Some letter of that After-life to spell;

And by and by my Soul return'd to me,

And answer'd ‘I Myself am Heaven and Hell!’

Omar, the poetic astronomer, might have added a stanza which would have closed: "I myself am God." This is, in effect, what Jesus did say: "I and my Father are one." This is as true of you and me and of every man, woman and child as it was of Jesus. Communism and Christianism pp. 80-81

The doctrine that we are all actually Gods and so require no leaders is close to that of the 5% Nation, also known as the Nation of Gods and Earths, popular in "Dirty Southern" Hip-Hop after Clarence 13X was expelled from the Nation of Islam.

True, Bishop Brown's Teachings of Marx for Boys and Girls from 1935 did have an airbrushed picture of General Secretary Stalin emblazoned on the cover, but Brown's Marxism was in fact too thorough to suit the brutal dictator of "socialism in one country": "It is all right to cry that we ought to let other nations alone. But it is futile. Nations are not built that way. Nations are made up of people, and human beings cannot let other human being alone. That is a law of human life." (Communism and Christianism p. 194) Human beings cannot let other human being alone. We are interfering monkeys!

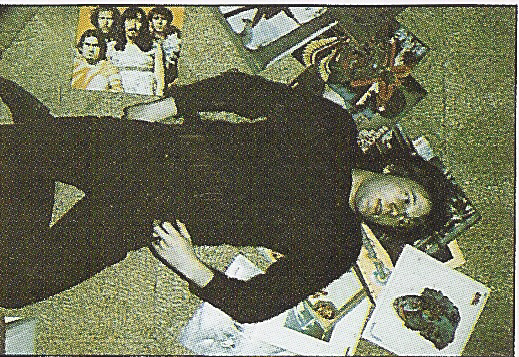

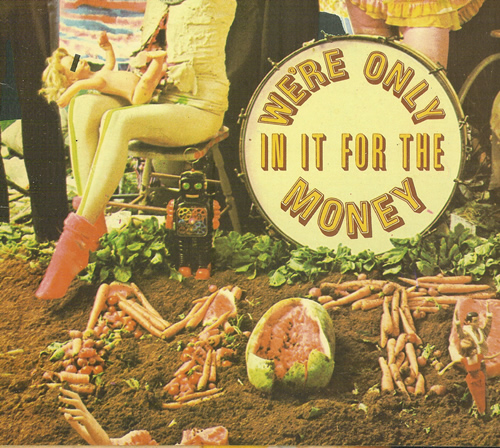

Okay, that was my preamble. I hope I haven't annoyed you too much by delaying talking directly about Zappa. In fact I'm being strictly Zappaesque. In 1978, the London punk band Alternative TV issued their first album The Image Has Cracked on the Deptford Fun City label. It began with a long track called "Alternatives", documenting the chaos, risk and stupidities of the punk scene at the 100 Club on Oxford Street, with audience members being given the microphone to explain what they'd do about social problems and starting a fight. All this before you got to ATV's pop-rock anthem "Action Time Vision", and "Why Don't You Do Me Right?", a rocking cover of an obscure Zappa b-side. Later, Mark Perry explained he was being "Zappaesque", making the fans "work" for their thrills. I'm doing the same thing here. Fawning fan worship, whether it's from The Idiot Bastard or Dweezil, is unZappaesque in my opinion. As Geronimo Black put it (The Image Has Cracked sleeve included a snaphsot of Perry lying on top of his favourite LPs, which included We're Only In It for the Money, so the face of Jimmy Carl Black actually stares out from the back cover): "You've got to wade through piles of shit to get to paradise".

(Bunk Gardner (tenor sax, alto flute, bassoon, piano, pipe organ), Denny Walley (slide guitar), Jimmy Carl Black (vocals, drums, tympani, ax, log), Andy Cahan (drums, guitar, organ, piano, pipe organ), Tjay Contrelli (tenor sax, baritone sax, vocal, flute, vocal), Tom Leavey (bass, background vocal).

The Talk

But now I shall get to Frank Zappa, which is after all the reason you've come here. The title of this talk is "Zappology, Or, Getting Our Hands Dirty". I want to start by saying that Frank Zappa produced an art that doesn't say "DO NOT TOUCH", art which recognises our meddling natures … If you visit an Art Gallery with children, you quickly learn that the first thing you have to teach them is DON'T TOUCH THE ARTWORKS. Art is the locus of the Sacred in liberal societies which have replaced the Divine with monetary value: art assures Big Money and Corporate investors that there is something ineffable today, even if it looks like rubbish (which it generally does). Zappa's art, on the contrary, is effable all the way.

In this sense, Zappa is Anti-Art, at least anti art as defined by the international art world, which is calibrated by money. Against this mercenary concept of art, Zappa asserts artistic use value versus exchange value. Use for us rather than value for them. This explains Zappa's animosity towards the Velvet Underground and David Bowie. Generally taken as an example of his intolerance, narrow-mindedness and bad temper, or some kind of West Coast/East Coast schism (or anti-Englishness in Bowie's case), this animosity was a reaction against an incursion of artworld values into the world of R&B. For Zappa, the "don't touch" injunction of the Art Gallery is an insult and an affront. Despite the fact that many European intellectuals thought the Mothers of Invention played Art Rock, he dismissed the genre: "Oh that music where the chords are all weird and the beat's no good?" he told an interviewer, "I don't like it". Henry Cow got it wrong.

Unlike artworks in a gallery, Zappa albums demand to be touched: you take the record out of its sleeve and place it on the turntable. The needle penetrates the groove. How did Pauline Réage describe orgasm to a child? "Quelque chose dedans qui gratte … qui gratte … qui gratte". Something inside which scrapes … and scrapes … and scrapes. That's how Zappa thinks of the operation of music on your tender soul. There's an extraordinary clip to be found on YouTube. It's a dad's video of his child responding to the title track of the record Zoot Allures. The baby is in the back of a car, in a baby seat, and responds to the music as if he or she is being stroked, tickled and caressed. Like the abstract painters in the 1920s, who wanted to access a natural language of colour and shape which would transcend cultures, Zappa's music seeks to communicate directly. However way-out it gets, it always seeks the primal communication of the blues. This primal communication is anathema to the post-structuralists, who insist everything must be about learned codes or we are trapped in natural reaction, sexism and ideology. Of course it's all about learned codes as far as they are concerned — they make their living by teaching them!

Deleuzian Zappologist Jonathan Jones pointed out that We're Only In It For The Money actually features the sound of a needle scraping across a record's grooves, and made this emblematic of his music's scratch and bite. For Zappa, music is a physical act. He first realised this, a child bored during a Catholic service, he watched the candles flicker as the congregation sang: music is about moving the air. This physical aspect is not eliminated, as some purists imagine, once the music has been recorded and turned into a commodity. On playback, volume is always an issue. The fact that it's impossible to talk over a Zappa record offends people in the rtoom who don't like music. The record cover sits on your knee. You pass it around. It needs to be held and looked at closely. Especially Frank Zappa records, which are like George Clinton albums, close-packed "statistical densities" of meaning (the opposite of artworld art, where everything is about denying meaning, the "less is more" aesthetic of the super-rich). You don't put a record cover in a bank vault, you roll a joint on it. It's a mass-produced commodity, a material object, not a sacred totem lifted above the dimension of time like the Chinese jar in T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets. Despite the fetish of the female body in advertising — a banal and sexist sales device which, unlike Sonic Youth, Zappa never exploited on his record covers — the capitalist imaginary is actually sexless: it denies the facts of life. As Zappa put it, explaining the song "I'm a Beautiful Guy" on You Are What You Is to a journalist: "Those yuppie guys sipping Perrier water and playing tennis, they think they're going to live forever. They won't!". The dream of capital is to replicate and expand itself without being used up, whereas (as every parent knows) sexual reproduction entails recognition of the ageing process — and hence recognising your individual mortality. For Zappa, these material facts of life are not a tragedy, the termination of faith and charity and hope, but something amazing — perpetually amusing and interesting. When his moustache started sprouting white hairs, Zappa made no attempt to hide the fact, but put it right in the face of his record buyers. On which record cover? Sheik Yerbouti. 1979. Zappa exposes the eternity of religion and the untouchableness of value as sterility and death: non-communication and oppression.

Since Zappa's own death, his records — or at least the legal "rights" to his music — have of course become an inheritance, a property … and under capitalism, property is untouchable and inviolable. The Zappa Family Trust tries to stop any activity around Zappa's music apart from incredibly tedious shows by his son Dweezil, which reproduce the albums with sterile fidelity. This is a fierce paradox, since Zappa's art is all about manipulation, risk, invasion, violation and change: the actual penetration of the cell wall we're confined in. Sex, in other words. People ask me, What is my book The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play all about? What is my "point"? What my "struggle"? It's this, friends, it's to make us all into Zappas, creative artists, revolutionaries in our own lunchtimes, freaks in our own right: to smash the alienation caused by veneration and respect, to use Zappa rather than consume him. Let me put it visually. … Here's what Zappa looks like as property, as a trade mark …

all smoothed off and polished and sickly … in fact it's "the great individualist" redesigned to resemble the Apple logo! ... but here's what I'd like us to do with his oeuvre…

I've ended up with my iPad sketch of Frank Zappa's moustache from the Sheik Yerbouti album cover of 1979. Note the white hairs.

Michel Delville and Andrew Norris call Zappa "maximalist". They connect him to the anti-clerical, all-inclusive, populist effusions of François Rabelais and James Joyce: full-blooded life as it's really lived versus guilt, oppression and "sin". This is a great coinage. Maximalism is the polemical opposite to Minimalism, the music style which took over in the academy when postmodernism kicked Serialism out of favour. In 1991, talking to Florindo Volpacchio of the American quarterly Telos, Zappa showed that, despite his disdain for book-based philosophy, he was up-to-speed on postmoderism, and was gracious enough to concede that it might have some claim to truth. But then, in a typical Zappa move — the kind of "shock" which is the gist, gristle and point of all his art — he blows postmodernist music like Minimalism to hell in a breadbasket … Here's what he said:

"[People say] … the only way … a composer can function in contemporary American life … is to do this shallow, empty, repetitive, disposable stuff, and then verify it or rationalize it by saying 'that's the way society is, and we poor composers can only reflect the way society is'. There is a certain amount of truth to that, but then on the other hand, Why the fuck bother to listen to it?" (Telos no 87 p. 127)

Staying loyal to the R&B he and Captain Beefheart listened to as teenagers, Zappa refused the style choice of the rich and wealthy, for whom a lack of action and content is a mark of distinction, an index of eternity. If you take a walk in London's Bethnal Green, where the poor of London live, you'll find shop windows crammed with amazing products — stuffed tigers, lamps in the shape of nude women, framed pictures of glittering waterfalls, fountain features with real water bubbling over rocks and imitation grass. But if you walk up Bond Street in West London, where the rich do their shopping, you'll find one silver bowl exhibited in a shop window, or a single oil painting. Even if he became a millionaire through his music and made his home in Laurel Canyon, Zappa's art always came from the poor side.

Zappa's Maximalism isn't just an attitude towards music or art, it characterises his thoughts about everything. Consider Venus at a Mirror from 1615 …

In the centuries since Peter Paul Rubens, for whom body-weight meant wealth and atttractiveness, the masses of Europe and America have had enough to eat, indeed poor people suffer from an excess of fat and sugar. So being "slim" has become a mark of distinction, a sign of class, of having the extra resources to consume expensive food and spend time exercising in exclusive gyms. Zappa repudiated this viewpoint in the song "Sex" on The Man from Utopia, where he sneers "Who wants to ride on an ironin' board?" and "Who wants to ride on a debutante?" while the chorus goes "The bigger the cushion/The better the pushin'". This is consistent with Zappa's Afrocentric worldview, as also expressed by R. Crumb and the militant hip-hoppers. For Zappa, love of big bottoms is not to be separated from musical aesthetics or philosophy or politics. Zappa's music is built on the bass, from bottom-up, which is why Scott Thunes was the most important musician in his 80s band. In his politics, Zappa sneers at the superstructure and empaphasizes the base. This crossing of sexual preference with music and politics breaks down divisions between the senses. Hence his sympathy for synaesthesia, the fin-de-siècle discovery that the "separate senses" are not really separate at all: Alexander Scriabin's "color-note organ", as refered to in "Florentine Pogen" on One Size Fits All. Roger Scruton, the conservative music philosopher, began his book The Aesthetics of Music (1997) by announcing that music is sound art aimed at the ear, whereas painting is visual art, aimed at the eye. Zappa has never subscribed to this kind of Kantian bureaucy, which locks speculative thought and the perception of the real in tautologous maxims. Zappa was forever making dialectical bridges between the senses, making record covers dialogue with the music inside, hearing spoken-word as music, or calling a guitar solo an "air sculpture", a spatial phenomenon as much as a journey through time.

Behind this sense-hopping is materialist monism, which populists and rebels have resorted to ever since St Paul injected Platonic idealist elitism Christianity and Emperor Constantine hijacked Jesus (previously a slaves' hero) for the ruling classes in 312CE. But Zappa does not argue this materialist monism philosophically, since for him all book-based authority, all concepts, are despicable priest-caste elitism; Zappa argues this materialist monism in every move he makes: in the sudden dadaist switches of his interviews; in the shocking segues of his recorded output; and in his purposeful incongruity as a media figure.

"Where do you get all the great ideas for your music?" asked an exceptionally dumb TV-interviewer. "I read them off the auto-cue" replied Zappa, a bizarre response which came from observing where the presenter was getting her ideas from as the interview proceeded. For Zappa, and for Beefheart, reality itself was a score which could be interpreted by a performer. "Metal Man Has Won His Wings", an early collaboration recorded at Studio Z in 1964 with Vic Mortenson on drums, was an amplified perforance of an old blues riff recycled by Duke Ellington and named "That's the Blues, Old Man". In 1951, it became a hit for Jimmy Forrest called "Night Train" (d uring his time in the Ellington Orchestra, the tune had been a tenor-sax feature for him). However, the version which most influenced the performance at Studio Z was James Brown's recording of 1961. Brown replaced Forrest's lyrics by shouting out the names of cities on the James Brown Band's itinerary during their East Coast tour, very like the "shout outs" made by hip-hop rappers today as they hail posses from local areas. The train is imagined as a gramophone needle in a record groove, playing the city-names as it passes along the railroad track, James Brown the loudspeaker, cementing a very old connection between beat music and train sounds. At Studio Z, Beefheart reproduced James Brown's performance by turning to a comic book pinned up on a bulletin board by the door and shouting out any words he could find: "Metal Man! Dirty water! Turpentine! Styrofoam! Chlorine! Crow bar! Death stroke! Mojo! Water spout! Twist and shout! Electro-flyer! Hawk man!". As well as sounding just like the words Beefheart later put together for Trout Mask Replica, these comic-book phrases are a concentrate of the new materials and technical buzzwords of the 60s, providing a better map of the combined minds of Beefheart and Zappa than "serious songwriting" could do, which is invariably constrained by previous literary models (just try reading Greil Marcus on Bob Dylan, this isn't musicology it's Lit Crit). Unless your name is Randy Newman, of course.

Beefheart's dadaist desire to let the material speak for itself, without the intrusion of the bourgeois artist with his or her over-wrought intentions and morals, pervades Zappa. It explains the frequent occurrence on the albums of spoken-word and field recordings, something which frequently alienates listeners with firm ideas of what "music" should be: but all is actually being shaped by an expanded sense of artistic form, which includes: the whole album, its place in the oeuvre, the details on the cover, Zappa's comments in contemporary live performances and interviews, the listener's own associations, and finally the Totality of the Cosmos. In the end, Zappa twists the neck of the vessel, so that instead of his art being a little tight knot at the end of the inflated pig's bladder of an ever-expanding universe, the whole of creation is reduced to shadowplay outside Zappa's work. You have entered his head and think like him. Some people stop there to admire the view, but esemplastic Zappaphiles press on, slog beyond, refuse to float in the trembling minuscus of a fly's eye. If we've graduated to perceiving the world like Zappa rather than staring at him in disbelief, the time has come for us to actively create too. Hello, Urban Gwerder! Or rather, realise, that in thinking about Zappa we were actually creating all the time. As the Canadian poet jwcurry says, rather than "being entertained", we should entertain Zappa as a guest in our own creations. The images I am about to show you were made using a paint app on a tablet, an interface which allows the user to register the wiggles of his or her friendly little finger as graphically as an electric guitar … Wishes are drawn directly here, without the mediation of fashion, money or power …

Along with Cal Schenkel and Donald Roller Wilson, Bruce Bickford provided some of the most striking visual moments in Zappa's oeuvre. By the time Zappa found out about Bickford's amazing and unnerving stop-animation with wax figures, he'd initiated "xenochrony". This focused many of the ideas which he and Beefheart had developed. Neither of them trusted the expressive individualism of singers like Bob Dylan and John Lennon. For them, there was something limiting and constricting about their concept of artistic persona and songcraft, almost as if these constituted a block to experience and reality. Beefheart chose a route of experimental musical re-organisation that required such devotion from bandmembers he was later accused of setting up a cult: he broke the "moma heartbeat" of Rock. Without him in charge, the Magic Band regressed to normal music. I quite like Mallard, but really they are the Eagles with a few weird touches. Disrupting the communal laziness of "the band" put each beat on edge, so everey guitar chord came as a shock. Beefheart then used his unique voice to glue the elements together, forcing his larynx into places only a maniac would go. "She drives a cartoon around" he sang on "Ella Guru": Beefheart's music is a cartoon driven around by a dadaist, its colours and shapes brighter than life, making Dylan and Lennon's music sound grainy and foggy and washed-out, like a 70s colour photograph.

Zappa, in contrast, did not reduce his musicians to Skill Degree Zero and build them up again from scratch. He deployed them for their existent skills, but in contexts that were bizarre, making a dada collage out of his human materials. For example — a small example, but an actual detail is always more interesting than a generalisation, however "wise" sounding — George Duke was a consummate pianist, having learned by ear in his mother's gospel congregation in San Francisco, then fine-tuning this musicality with college lessons and jazz playing. He was upset when Zappa asked him to play piano triplets, the sort of thing Doo Wop singers would do at the piano with no "pianist" around. But the truly weird moment for Duke fans is seeing him in 200 Motels playing trombone behind "Indian of the Group" Jimmy Carl Black on a country-and-western song. Trombone? Turns out this was his second instrument when he studied piano at college. Trombone is also an important instrument in gospel music. Duke obviously thinks it's hilarious to be playing trombone on a redneck skit like "Lonesome Cowboy Burt", it's revenge for the racism he's received in his life.

Zappa repeated this collage process — taking something out of its original context and reinserting it somewhere else — with Bruce Bickford. Instead of asking him to animate one of his pieces of music, or making new music to accompany one of his animations, Zappa simply combined the two. He obviously felt that Bickford's art was so close to his, they belonged together, that it would "work" and he was right — it's bizarreness squared. Both artists are obsesively meticulous about what they do, each second is action-packed, overflowing with detail, but this semantic overload all serves an imaginative drive which is very familiar. It's like the sequence of images which takes over when you fall asleep, the subordination of external perception to the wilful impulses of the sensorium. Dream logic makes Zappa's music and Bickford's animations fuse and amplify each other, the erotic determination to manipulate and interfere, to meddle with the stuff we're looking at and hearing, to produce it, to poot it forth (to quote Zappologist Paul Sutton quoting Zappa) rather than merely suffer it, consume it.

When Sal Marquez played mute-trumpet solos on Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo, bewildered reviewers from Rolling Stone and New Musical Express — totally unaware that Zappa was pursuing discoveries made by Charles Ives, Charlie Mingus, Don Ellis and Conlon Nancarrow about complex and superimposed metres — thought Zappa was following Miles Davis into jazz rock. But listen to In A Silent Way! Its aesthetic is cool, frigid, hands-off. It's jazz imitating the disengaged "less-is-more" style-choices of the elite. Nothing happens musically, there is no penetration or transformation or surprise, instead the music reaches a kind of stasis (In a Silent Way is the origin, actually, of Manfred Eicher's ECM catalgie and Brian Eno's "Ambient": music as aural wallpaper). On Eric Dolphy's Out To Lunch, drummer Tony Williams disengaged his beats in order to open up Monk-like lift-shafts and Varèsian black-holes, forcing the musicians to make new, bright, anti-gravity relations like a late-Kandinsky abstraction. On In a Silent Way, Williams' boogaloo shuffle is simply an inert backdrop to Joe Zawinul's foreshortened blues-organ chords and John McLaughlin's filler guitar. Everything just is, timeless and mystical, there's no contradiction or conflict or development. Whereas the music of Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo is all about crises and questions (this was Zappa's name for "Christians" in his pachuco-epic short story about Emperor Cleetus Awreetus-Awrightus in The Grand Wazoo), In a Silent Way provides an answer: lay back, appreciate, be wowed by the endless hypnotism of a modal monochord.

William Blake , the great London revolutionary visionary who, like Zappa, no-one understands without engaging in interminable, intricate and indecipherable fucking arguments with their coevals and contemporaries, believed that aesthetic choices — whether to use outlines in painting, or adopt "Venetian" chiaroscuro — were not innocent, but flags of war. By their aesthetic choices his contemporaries revealed their true natures, and he observed how the brilliant new illusionism of oil painting discovered in Italy and developed in Holland was serving the heardhearted bastards who were throwing peasants off the land — the enclosure of the commons — and packing the poor into cities where they were overworked in foul conditions. Blake's aesthetics were interpreted as "mysticism" in the nineteenth century, and only when James Joyce, Allen Ginsberg and the art critic John Berger wrote about Blake did people begin to understand that Blake's art war as part of a popular struggle against capitalism. I am arguing the same for Zappa. Certainly, he saw through the corruption that was Soviet Communism and had no time for American unions run by the mafia: Zappa was not "leftwing" in the political or "identity" sense, but he did, like Blake, see that aesthetic choice was not innocent and conveys an orientation towards society and cosmos. And he was outraged by what he saw.

To finish, I am going to take you through some details from Frank Zappa's record covers … I have been kindly supplied with a CD player, but I don't want to prove points by playing Zappa's music, since each play of a track always alters my opinion, and my argument will dissolve into incoherence. However, we will listen to some of Derek Bailey's guitar as we look at the images. I played a record by Derek Bailey and John Stevens to Zappa when I visited him in 1993, and he said it sounded like him playing, with one hand on the guitar and the other at the drums. I took this as a compliment, but Bailey disagreed, calling Zappa "an arrogant fucker" for thinking he could do the work of two musicians on his own. Anyway, I consider Derek Bailey to be another William Blake in the field of music, someone who makes aesthetic choice out to be more than simply taste or an expression of identity, but to be symptomatic of deeper orientations, a test — basically — of your worth as a human being.

That would be reason enough to listen to some Bailey, but there's something more. Bailey divided music into two kinds, both equally valid in his estimation, but very different. Some music— I think he was thinking of saxophonists actually —he called "vocal", it's all about the voice. His favourite listening at home was Black American gospel and soul singers. Another kind of music is "digital". He didn't mean anything to do with numbers and computers, he meant coming from the hands. He was thinking of guitar playing and drumming. There is a whole tradition in the West of talking about social struggle as a dispute between the head and the hands; the elite favour Plato, who believed that ideas in the head are the gold which creates the world, whilst the labouring masses know that everything in civilisation only works because someone put it there: the manual labourer (and by this I include what people call "immaterial labour", since this is generally now working at computers, which is work for the fingers) knows the importance of hands. George Novack is good on this, in his book about the evolution of a scientific view of the world, Originsof Materialism (published by Pathfinder in 1965). Anyway, Derek Bailey is a very "handy" player, allowing his fingers to run ahead of his concepts, and I think it should be ideal accompaniment to this sequence of images, which were chosen to illustrate how often Frank Zappa put hands in the picture. In a modern urban setting, and in most pretty landscapes actually, everything is only there because someone put it there, generally by hand … or using a machine controlled by their hands … Derek Bailey is playing with Tony Oxley, probably the best drummer in the history of the world, who plays Elvin Jones cubed and believes that being a musician is about developing what you do piece by piece, by hand, not copying other people … Due to the internal politics of Free Improvisation in England, I hadn't discovered what Tony Oxley was capable of when I visited Zappa in 1993 … If I had, I'd have played him what I am going to play you now … If you get the chance, try and catch Oxley with Cecil Taylor, it will shatter your idea of what music can be … This is a track from a CD The Advocate released on John Zorn's Tzadik label in 2007. Bailey and Oxley were recorded together in London in 1975…

The Hands

PLAY: Tony Oxley/Derek Bailey "Medicine Men" The Advocate (Tzadik, 2007) 3:52

On Absolutely Free, a hand reaches up to grab Zappa by the neck, as if he's a giant billboard dominating the band …

… on WE're Only In It For The Money , the hand of a tailor's dummy penetrates the tableau pastiching the cover of Sgt. Pepper …

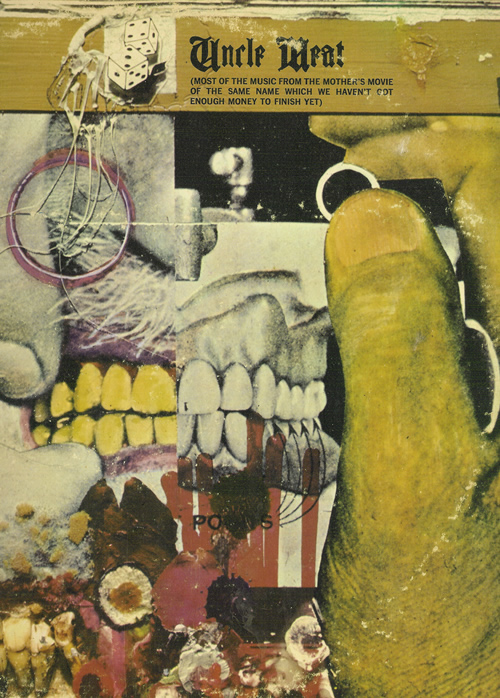

… on Uncle Meat , the hands of the concentration-camp warder push back the lips of the Jew or Communist internee, searching for gold teeth …

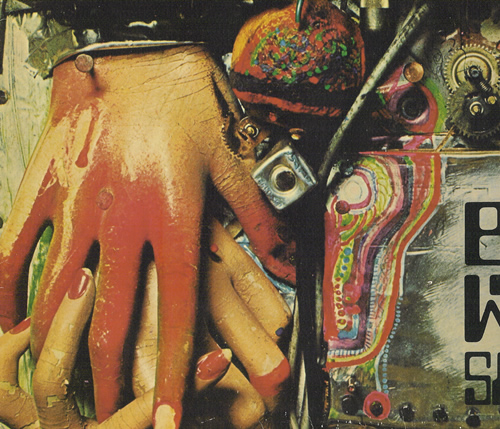

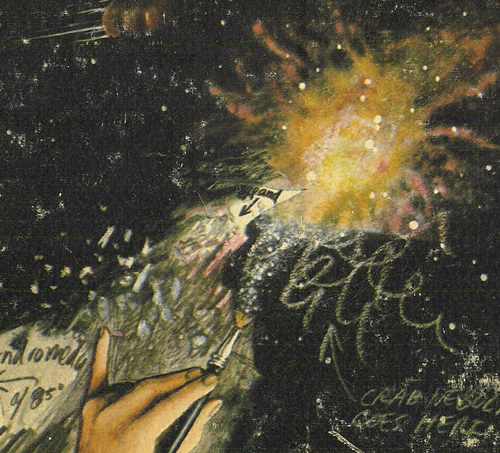

… on Burnt Weenie Sandwich hands are nailed Christ-like to the machinery of modern life, with graphic drops of blood like an icon on the wall in a Catholic seminary …

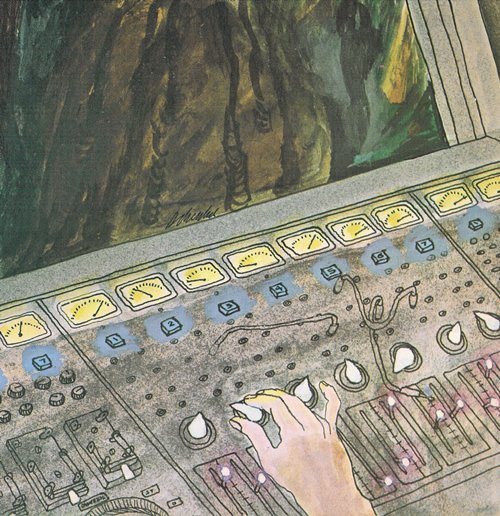

… inside the gatefold of Chungas Revenge we see the sound-producer's hand controlling the recording of the mutant industrial vacuum cleaner …

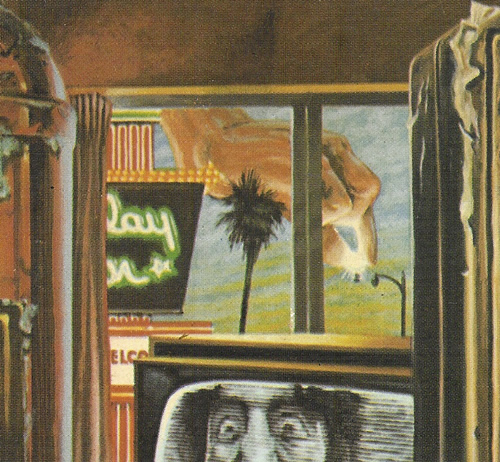

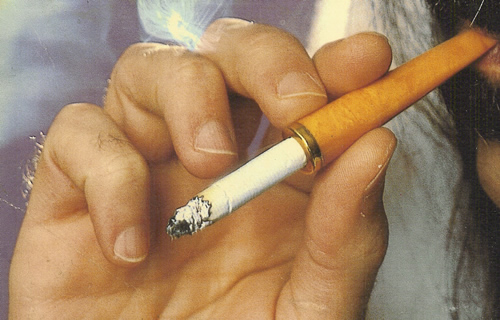

… on Overnite Sensation a hand penetrates the picturespace to take a cigarette …

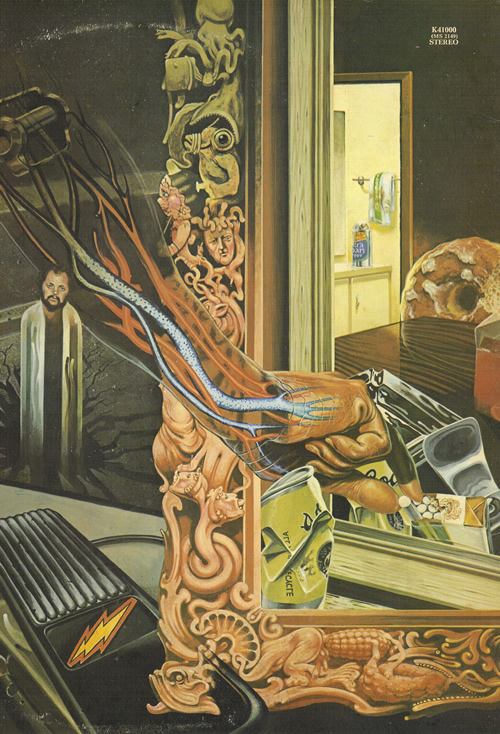

… and a hand fixes a streetlight as if we are living through The Days of Perky Pat or Truman's Story, living in a "handmade" model environment, which of course we actually are, it's just that work under capitalism is unseen and unsigned …

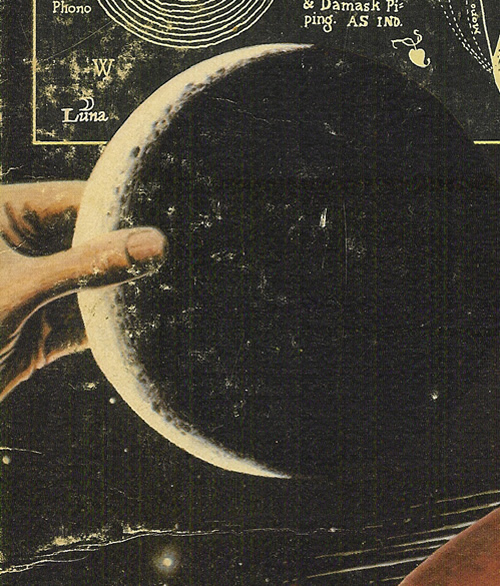

… on One Size Fits All a hand installs the moon …

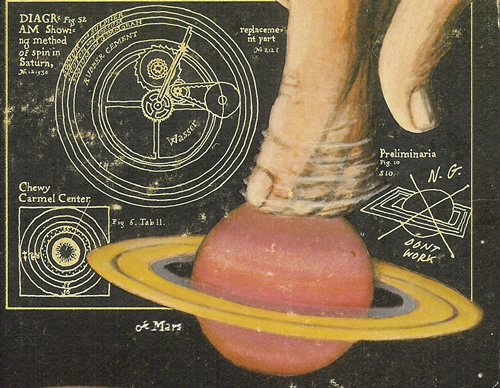

… and puts the spin on Saturn, God's hand revealed as an absurd projection of human labour …

… while it's the hand of Cal Schenkel, the artist, who actually puts what we see in place …

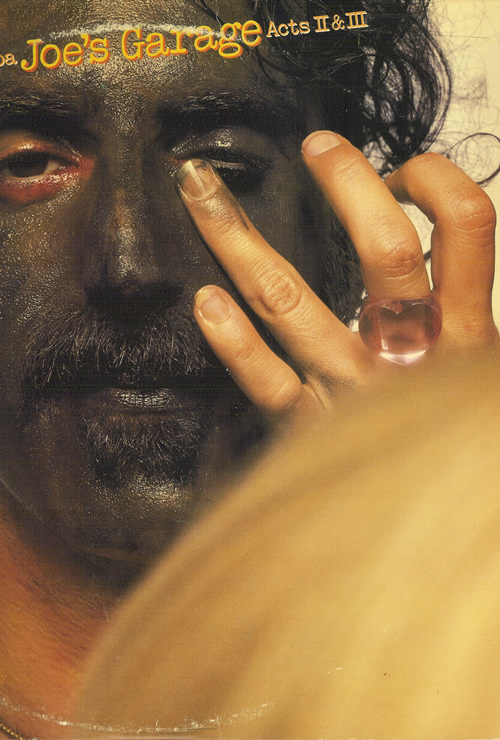

… Sheik Yerbouti smokes his cigarette …

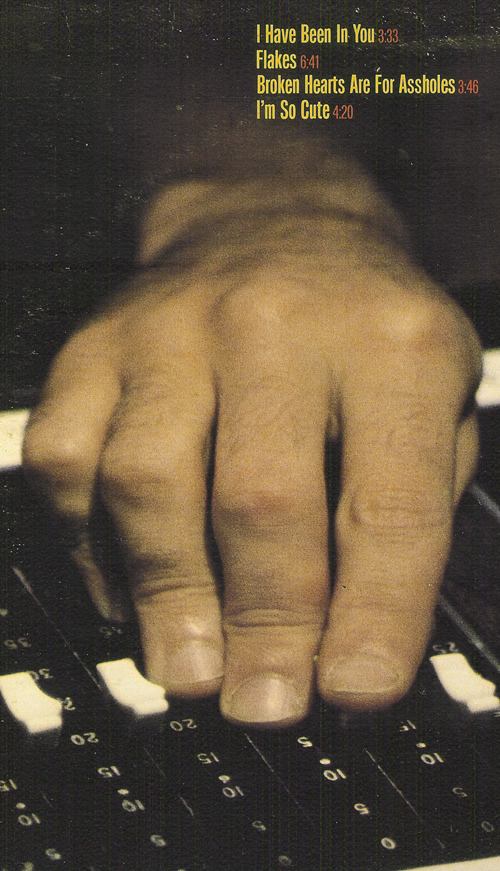

… and controls the sound, all entertainment the result of work …

… even Al Jolson-style blackface the result of work …

… the psychology of chemist and housewife at work not so very different, all daydreaming as they get the right thing in the right place using their hands …

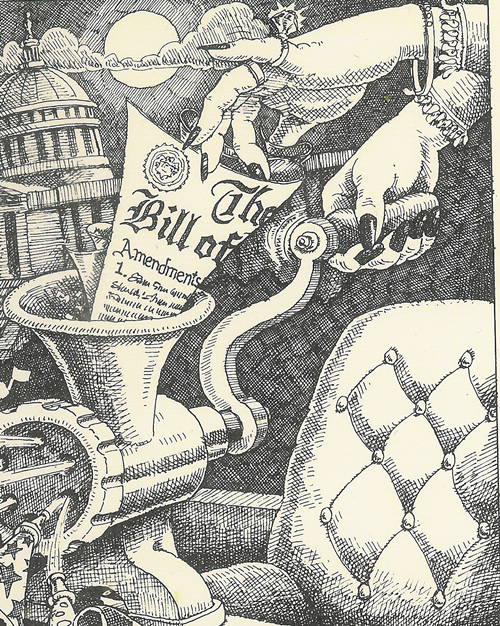

… we manipulate and are manipulated, here the Parents Resource Centre in Washington shreds the Bill of Rights …

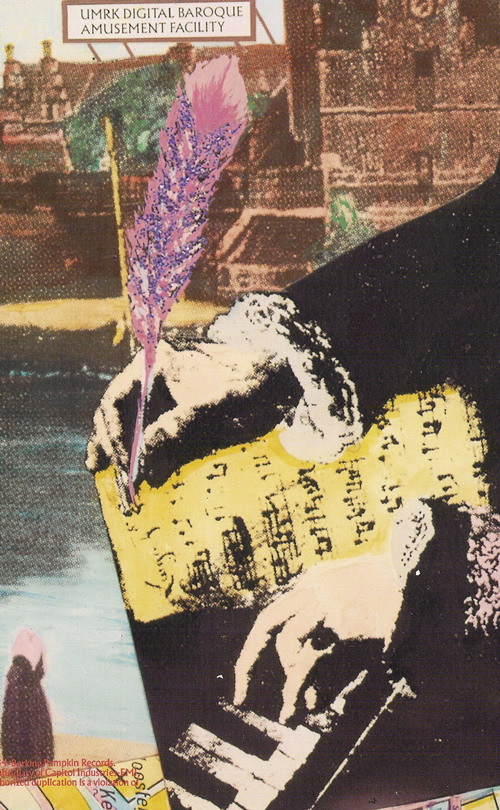

… and Francesco Zappa uses his hands to play a chord and write it on a score …

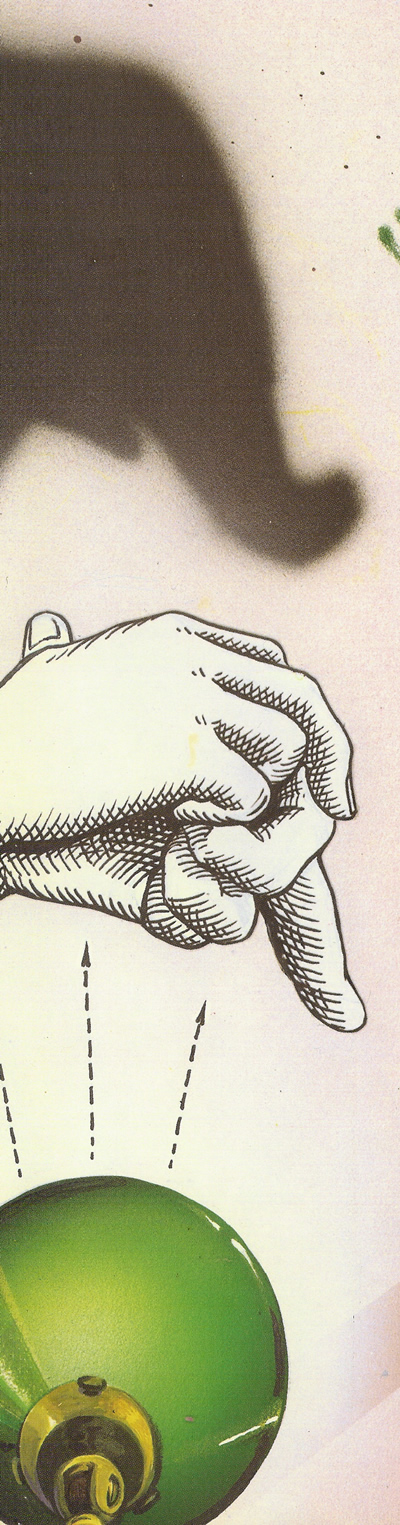

… whilst corrupt Republican presidents treat us like children and pretend there's an elephant in the room … but it's only their hands and a shadow on the wall … that last one from the inner gatefold of Broadway The Hardway, the album of new material from Zappa's 1988 and his most explicitly political album since We're Only In It For the Money …

Finale

Now I don't know if my argument is getting to you, or simply annoying the fuck out of you, but I'm going to let Derek Bailey's hands twitch some more and show you the results of letting my own hands scrabble free on the surface of a tablet running a painting app called Doodle Buddy …

… that's it! Thanks for listening ...

Postscript: Two "Coincidences"

As usual, poking around in the fetid tangle that is Zappology, synchronicities started emerging. Two, actually. (1) Crossing R1, Antwerp's ringroad motorway, on my way from the hotel to the venue, I was accosted by Henk Robben, a Zappa fan I recognised from several Zappanales in Bad Doberan (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern). "I'm interested that you use Trotsky to write about Zappa," he told me, "I was a member of the Fourth International for several years and I like that manifesto about artistic freedom Trotsky wrote with André Breton …". We parted, and the next thing I know is I'm staring at a hoarding with a photograph of a guy named Wim Werflieder wearing a hard hat and standing in front of the Antwerp skyline. A gigantic speech bubble comes from his mouth. It reads: "Ik ben trots op wat wij doen." IK BEN TROTS??? Surrealism still exists if you know where to look. (2) Then, returning to my hotel in the evening, having told everyone about the importance of hands in Zappa's oeuvre, with a Power Point display of the many hands on his record covers, imagine my surprise to find in the hotel lobby a row of twenty mirrors, each one with a photograph of a hand, hands from all walks of life and peoples of the world. The hand, apparently, gave the city its name (all to do with a story about a troll who’d cut off your right hand if you didn’t pay him for crossing the Scheldt). The dovetailing of imagery is something achieved by the world itself, not the intent of the artist.