Back to Zappology

PARANOID PERCEPTIONS IN THE FIELD OF ZAPPOLOGY

It was zappologist Jonathan Jones who pointed out that Frank Zappa's oeuvre creates a "paranoid listener". It's this feature which creates a special bond between those touched by his themes (hello Gamma), where such seemingly insignificant facets of life as fuzzy dice, dental floss, string beans and Kaiser Rolls assume iconic status. One such case is documented here before you, triggered by a record lent to me by a Somers Town neighbour called Ray Kane (well, actually, Ray lives on the other side of Crowndale Road, but let's not be pedantic). Hailing from Liverpool and growing up contemporaneously with the Beatles, Ray has had brushes with the music business - tour managing for local bands in the mid-60s, working his way up to association with Robert Stigwood, and doing promotional work for Flo & Eddie in the early-70s. Ray was also involved in the pub rock/punk explosion of the late-70s, working for the Ace and Chiswick labels. I was interested in the way Ray's involvement with the music industry peaked when things were real and relatively uncapitalised, and troughed in the years of plastic stars and corporate hegemony. So I got Ray on as a guest on my radio programme "Late Lunch With Out To Lunch" (every Wednesday at 2.00pm on Resonance 104.4 FM - if you live in London, tune in, if not try www.resonancefm.com on that day and time - 2.00pm UK time). Ray brought in some records to play, including one whose cover caught my attention immediately.

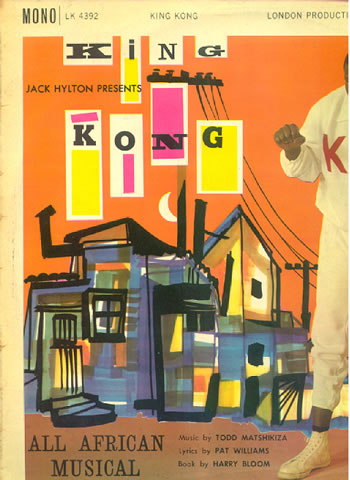

This LP was recorded by the cast of King Kong, a South African troupe, whose musical opened at the Princes Theatre, London, on 23 February 1961, after having taking South Africa by storm. The "Jack Hylton presents" on the cover seems to have been added simply as some assurance of quality entertainment: the music was by Todd Matshikiza and musical direction by Stanley Glaser. The sleeve carried this message on the back: "No theatrical venture in South Africa has had the sensational success of King Komg. This musical, capturing the life, colour and effervescence - as well as the poignancy and sadness - of township life, has come as a revelation to many South Africans that art does not recognise racial barriers." Most of the songs are dated sub-Sondheim, but "Gumboot Dance" allows in some pretty infectious rhythms, recognizable as authentic from the work of South African exiles in London like Chris McGregor, Dudu Pukwana and Louis Moholo, and brought into early-80s punk clubs by Neneh Cherry, Gareth Sagar, Mark Springer, Sean Oliver and Bruce Smith as Rip Rig & Panic. "King Kong" did not refer to Edgar Wallace's giant ape, but to Ezekiel Dhlamini, a Zulu boxer who became a folk hero for his disrespect of authority (he apparently derived his name "King Kong" from a film poster). Dhlamini's meteoric rise to the top of South African boxing dwindled into lost bouts, drunkenness, off-ring violence and murder. He knifed his girlfriend when she arrived in a club surroiunded by rival gangsters. He asked for the death sentence, but got 14 years hard labour - and drowned himself in March 1957 at the age of 32: a perfect story for the first township musical.

King Kong's proto-hiphop tale of triumph and tragedy casts an intriguing light on the title of the tune "King Kong", Zappa's "Caravan" for spotlighting the soloistic virtues of his various bands. On stage, Zappa once explained the story of "King Kong" as "there was a giant ape who lived in the jungle in Africa - some Americans decided they could make some money by bringing him to this country, then they killed him".

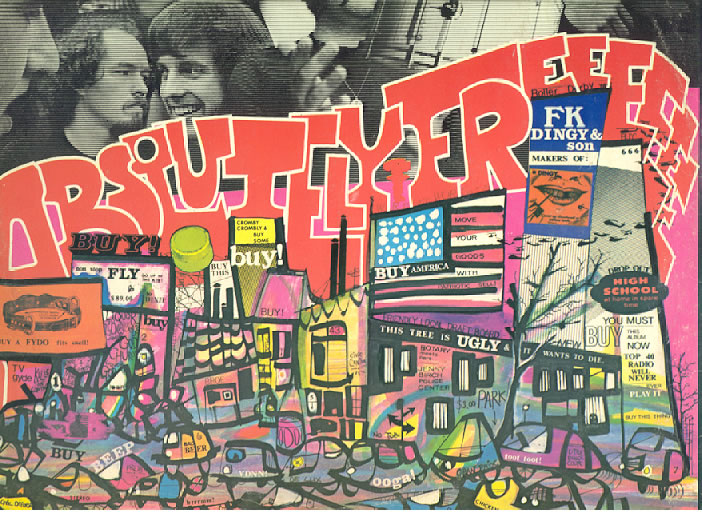

Decor and costumes for the King Kong musical were by Arthur Goldreich, who also designed the LP cover. Goldreich was a leading architect and visual designer in Johannesberg, a Jewish Communist who was arrested by the apartheid regime in one of the clampdowns in the early-60s. His cover supplies one of those bizarre "coincidences" which make Zappa's "paranoid listeners" prick up their ears, take a deep breath and check their historical-materialist sanity. In 1967, disgusted with the mess Verve had made of his text and photographs with Freak Out!, and applying the skills he'd learned doing graphic design for a greetings card manufacturer, Zappa constructed his own cover for Absolutely Free. The way he chose to depict a typical American high street is uncannily like Goldreich's style: loose washes of banded bright colour pinned down by bold strokes of black paint, paying particular attention to the skyline of an insalubrious urban neighbourhood (tin chimneys with conical hats to keep out the rain, telegraph poles and telegraph lines, cramped, higgled-piggledy housing, barred windows).

It's as if Zappa is bringing out all the political and social implications of Goldreich's design, a kind of Tourette's Syndrome avalanche of modern urban horrors. Where Goldreich had a barred door and window, Zappa has a "Jenny Birch Police Center", implying incarceration and corporal punishment (note the black face peering out of one of the barred windows). Using Lettraset and pen, Zappa names the mechanisms of social control and humiliation: religion, TV, liquor, hard sell. A stream of helicopters on the right reference the key weapon used by the US establishment against both the Vietcong and protesting students. Just like on the record ("Uncle Bernie's Farm"), Zappa draws connections between commerce and militarism: "War means work for all"; "Buy America: move your goods with patriotic sell". A high street choked with aggressive, bumping traffic illustrates the Sacred Cow of the post-war capitalist economy: the private car, with its pollution of the atmosphere, danger to pedestrians, encouragement of Fast Food ("chicken delete") and wars for oil.

The voice of reason might explain the "coincidence" between these two designs as perhaps a common commercial style, derived from a handbook or even a box of inks-with-instructions. However, Goldreich was a prestigious artist and designer: would he have adopted an off-the-peg style for the cover of a politically-momentous musical like King Kong? As usual with Zappa, we're left unassured that "he knows what he doth" (to quote Rance Muhammitz in 200 Motels). However, to picture Los Angeles like apartheid Johannesberg - whether or not by design - makes a powerful political point, and one also made by Philip K. Dick: if you're black in America, it might not be so crazy to believe that you're actually living under apartheid. Like György Lukács, who admitted after being investigated and harassed by the KGB that Kafka's writings were more "realist" than he'd thought, maybe Zappa's "paranoid listener" is just seeing things as they actually are. It hurts that Frank's not still alive, because whether or not he'd ever seen Arthur Goldreich's cover, I know he'd have found the correspondence fascinating.

Ben Watson

11-x-2003

Back to Zappology