On Frank Zappa for the Philharmonie

Investigations of a Dog: Stink, Instinct, Distinction

Esther Leslie

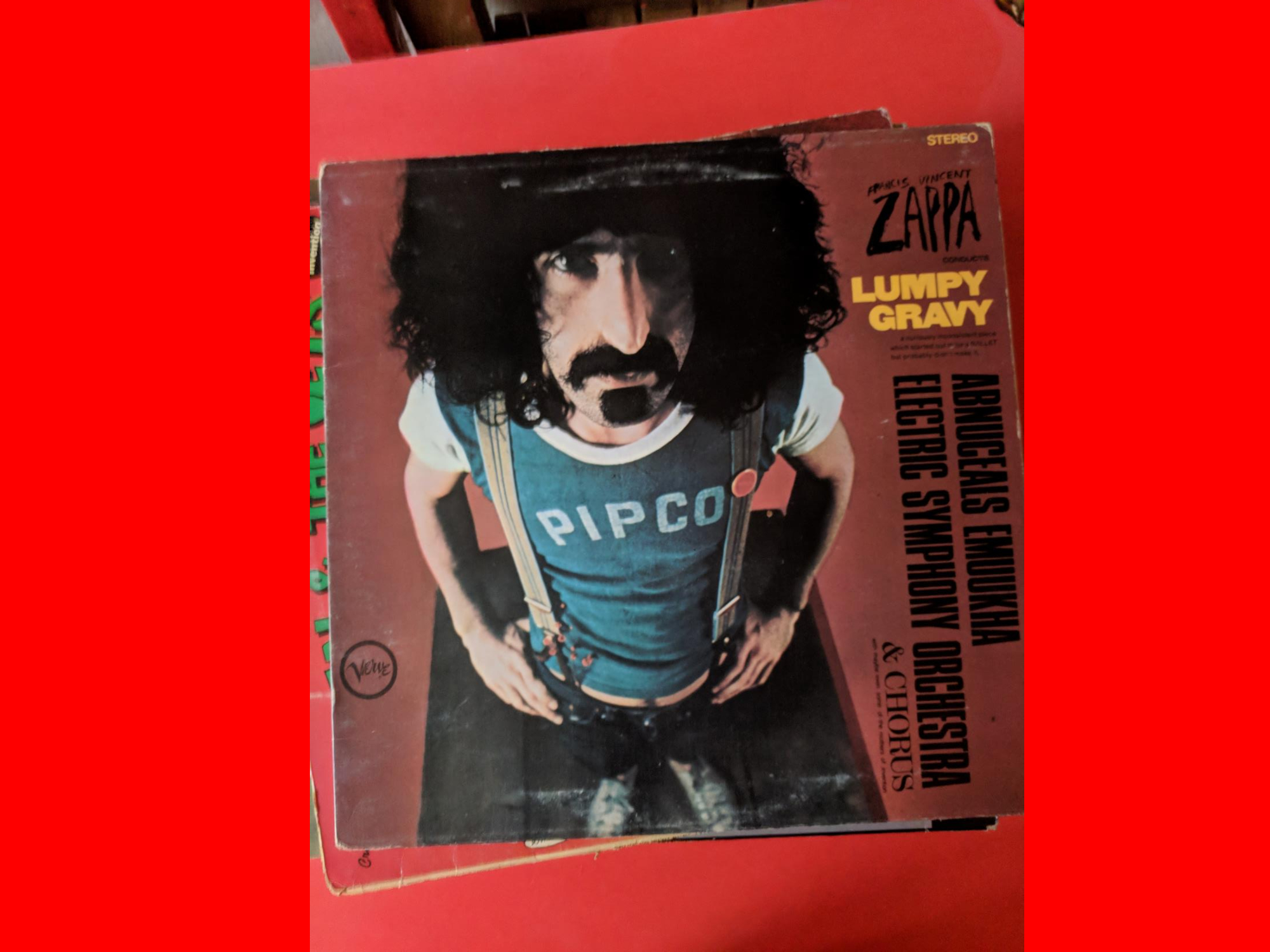

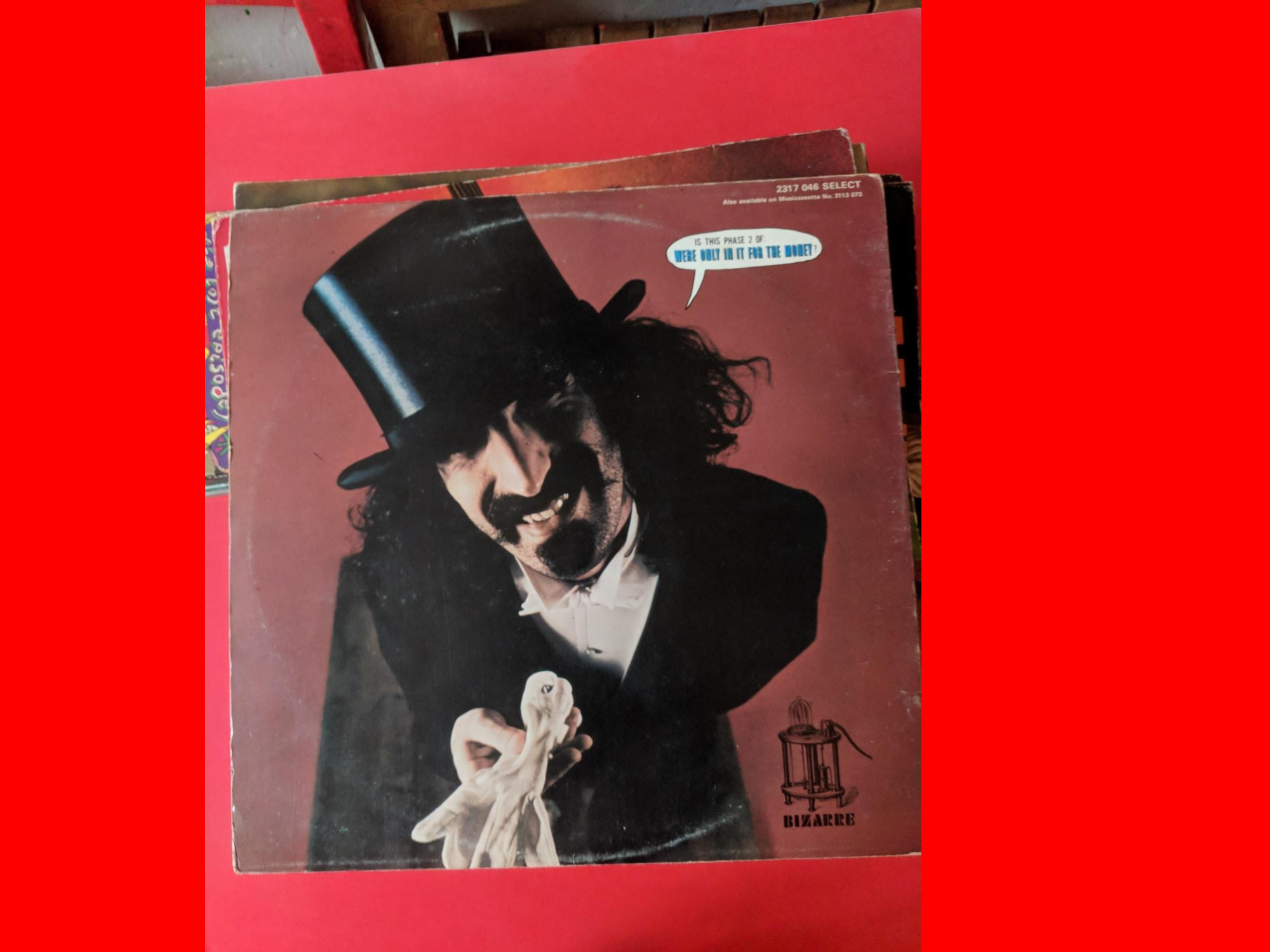

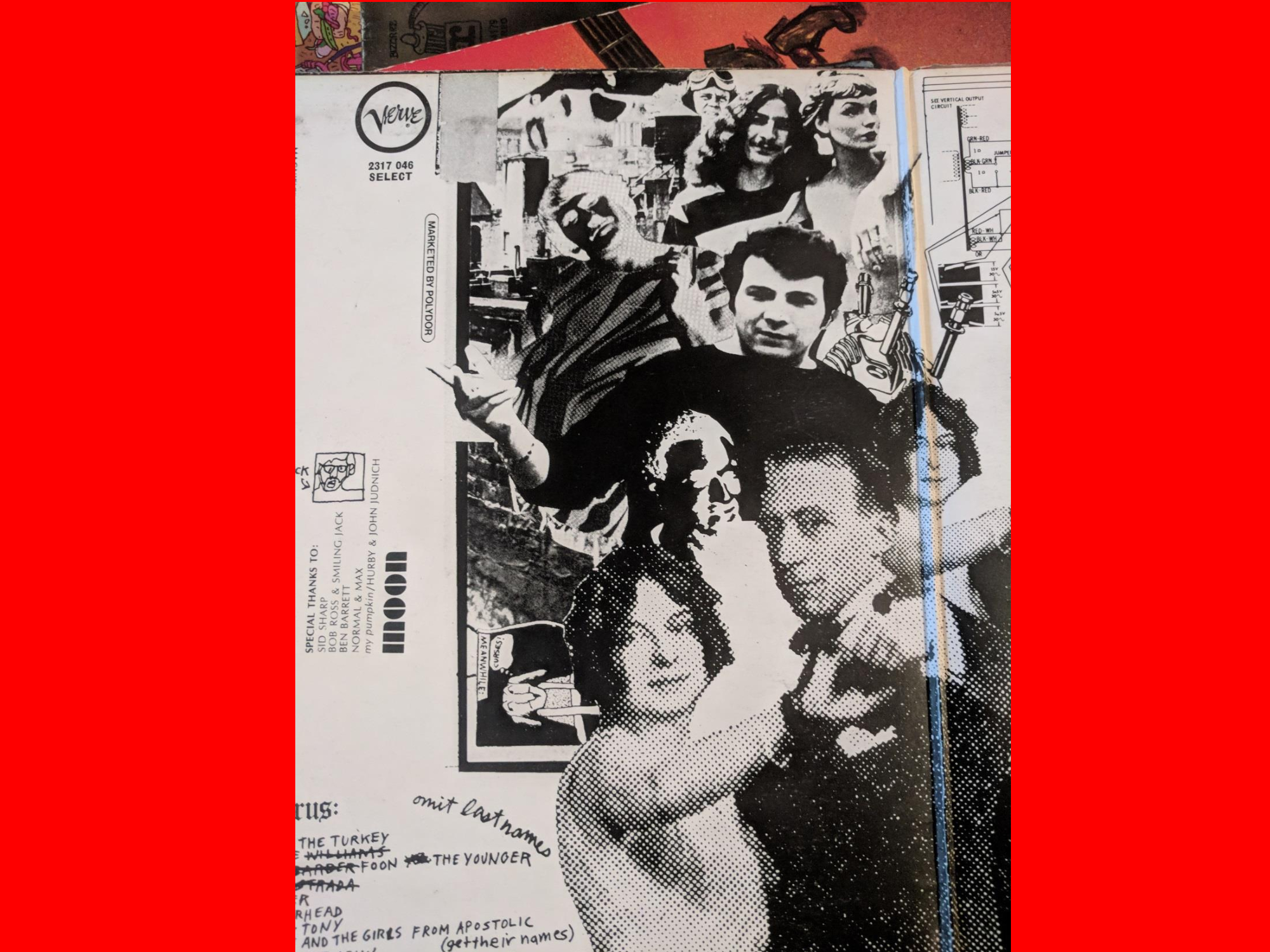

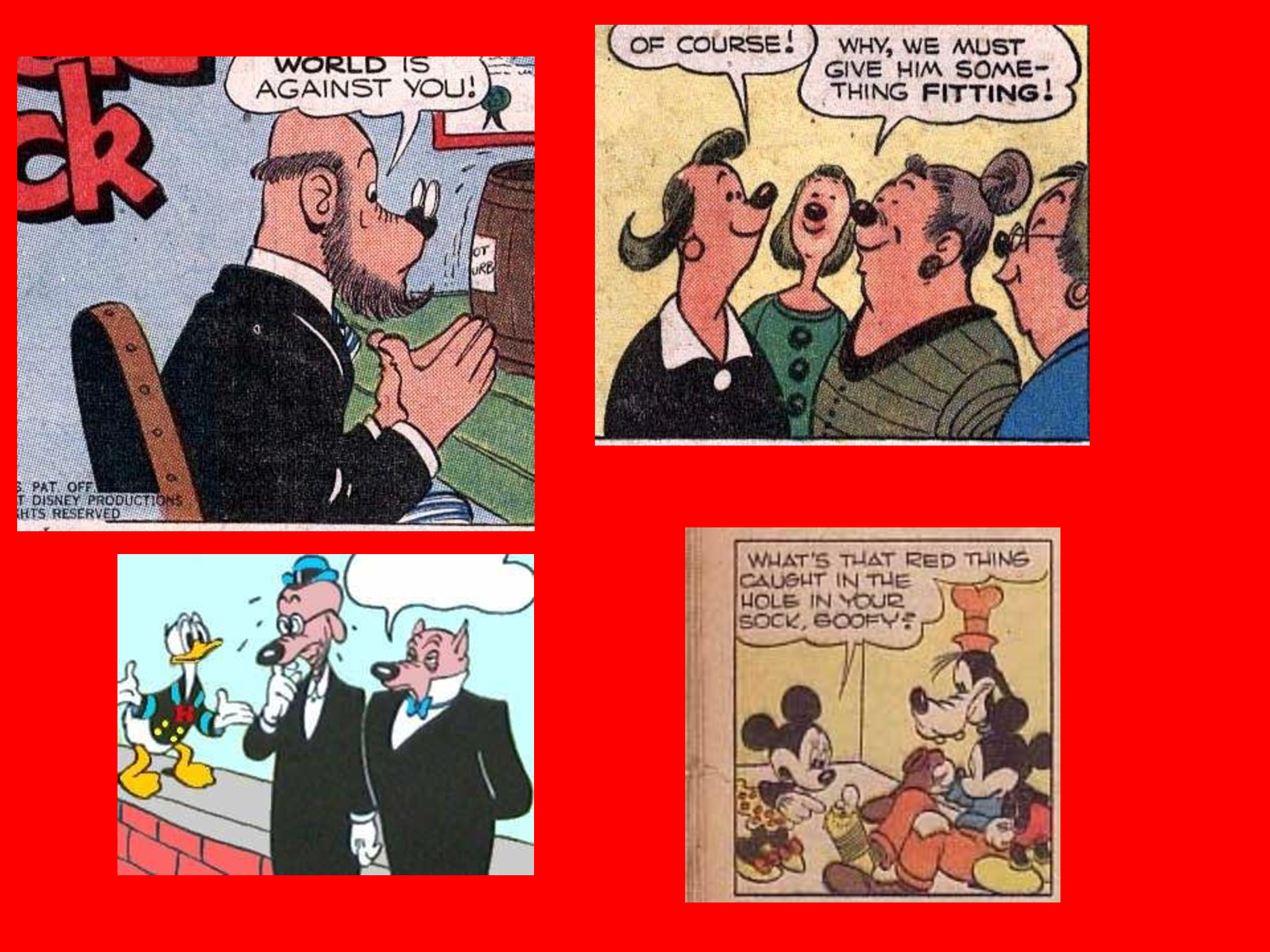

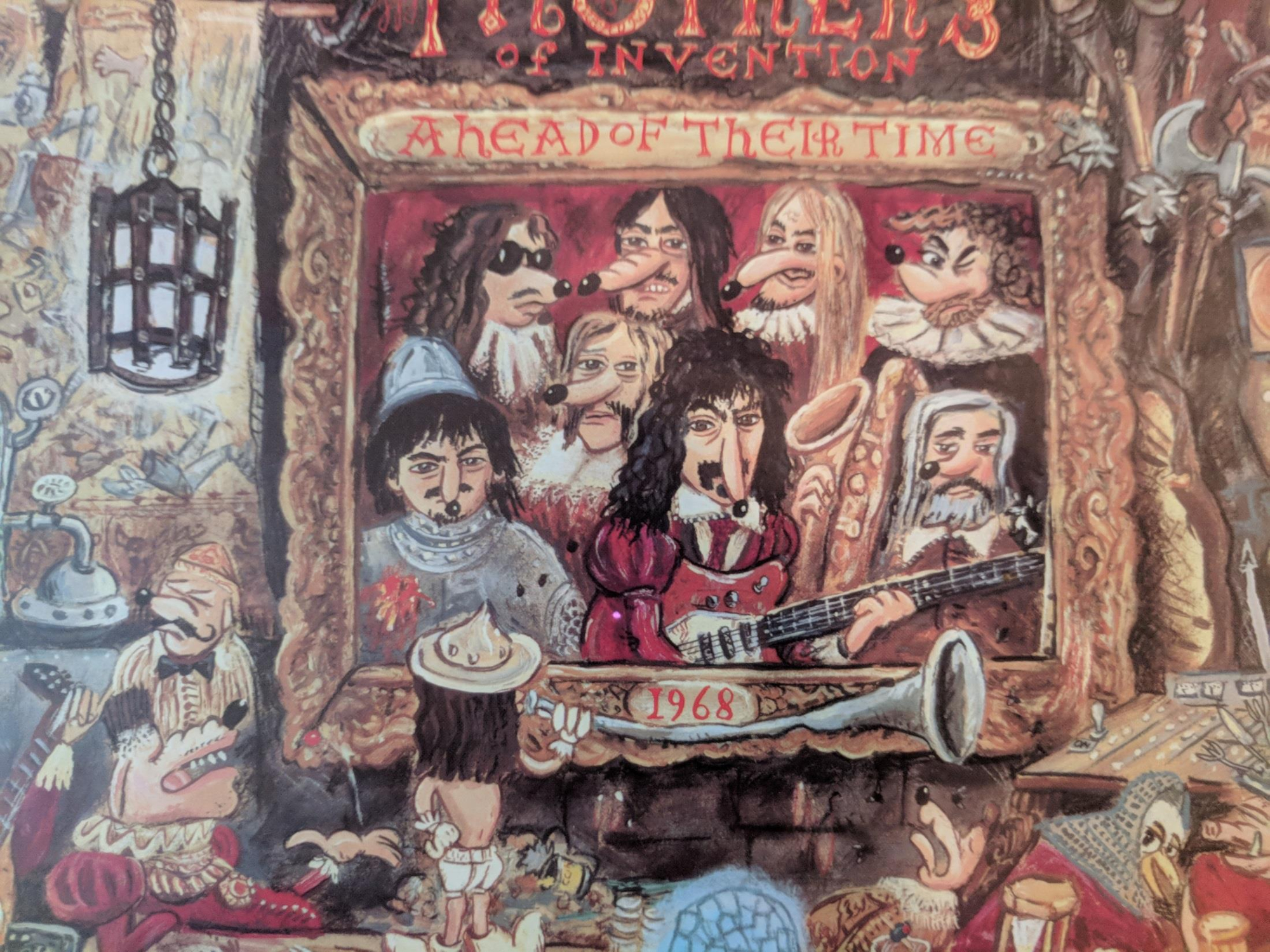

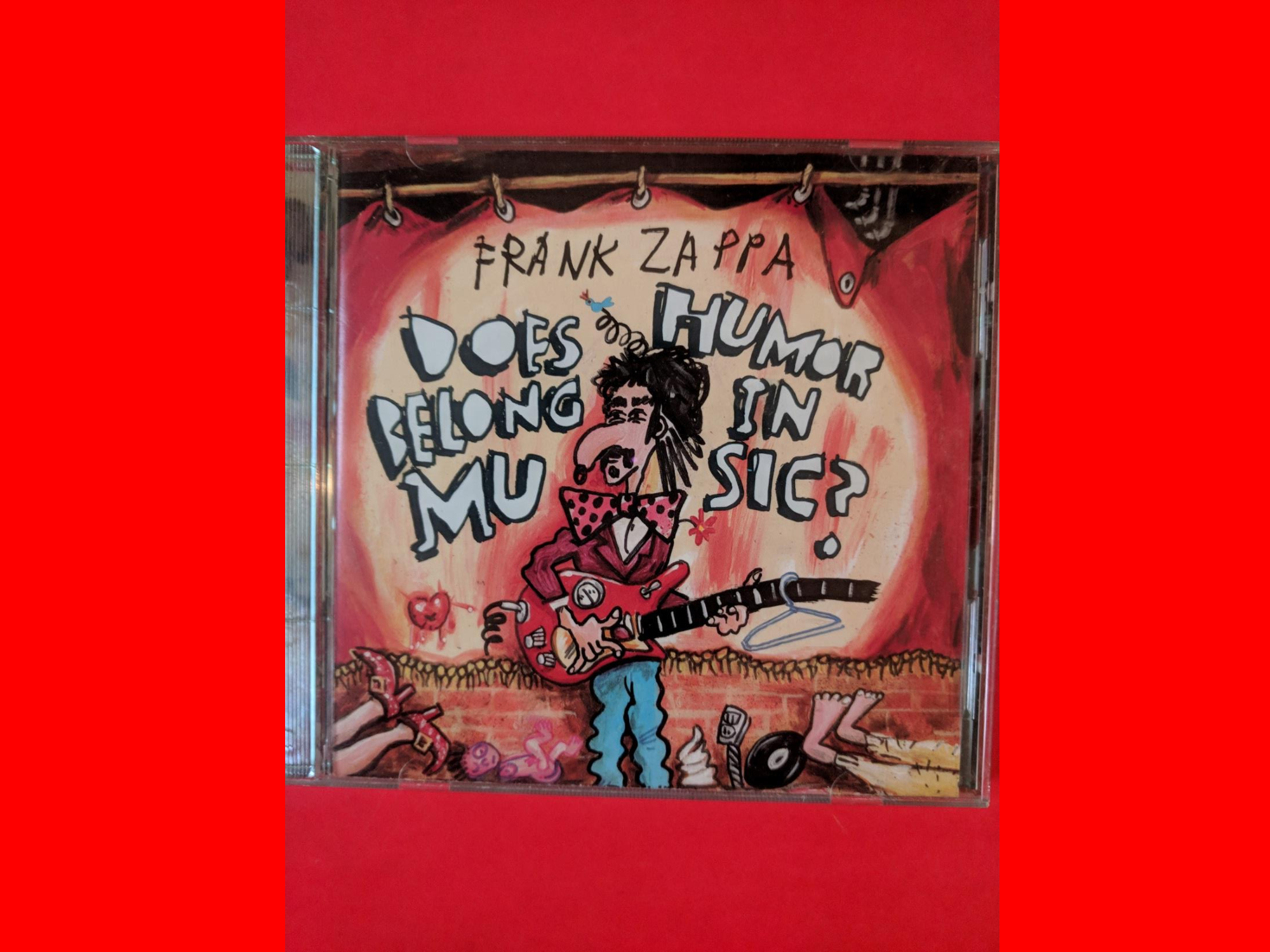

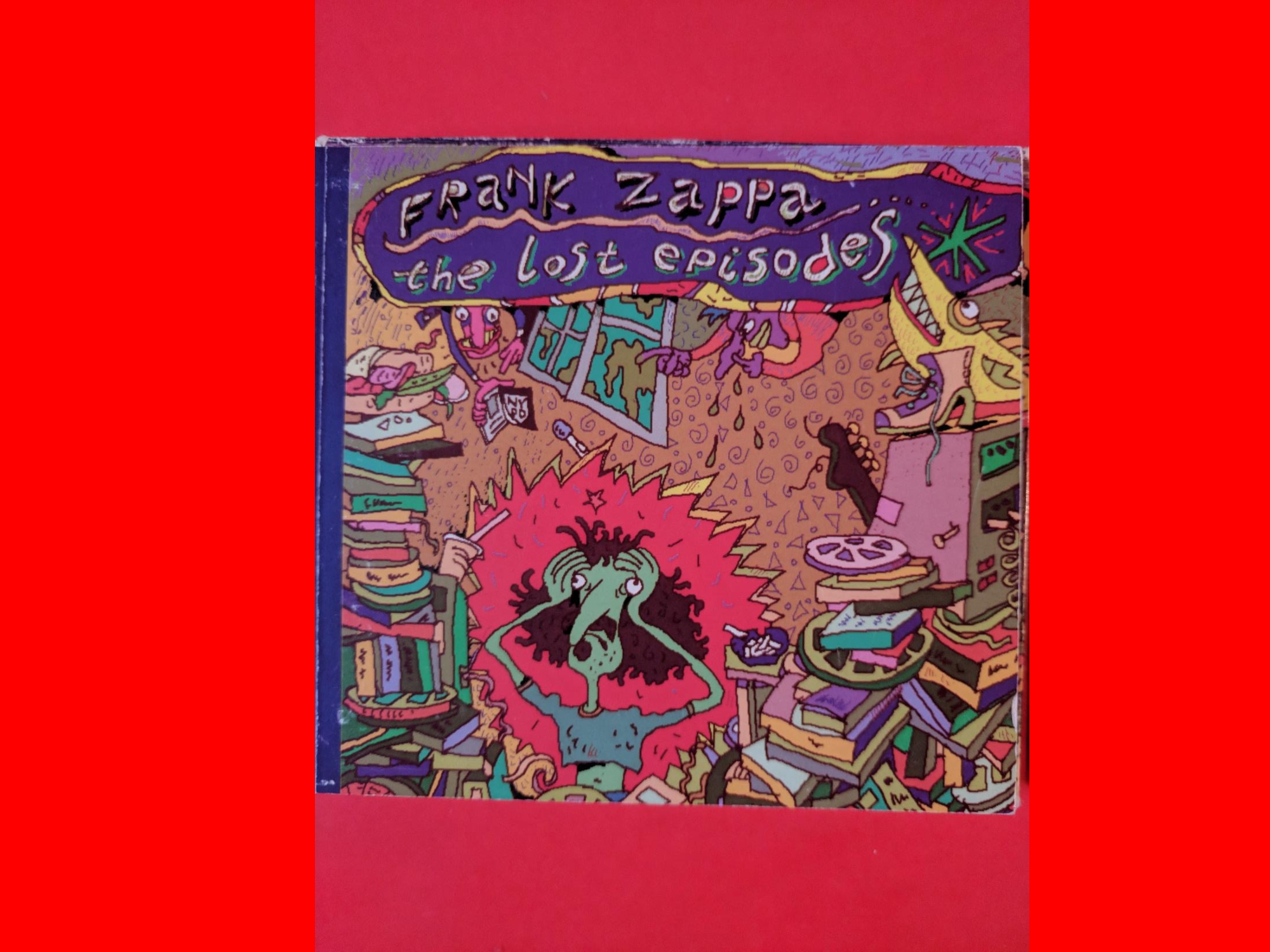

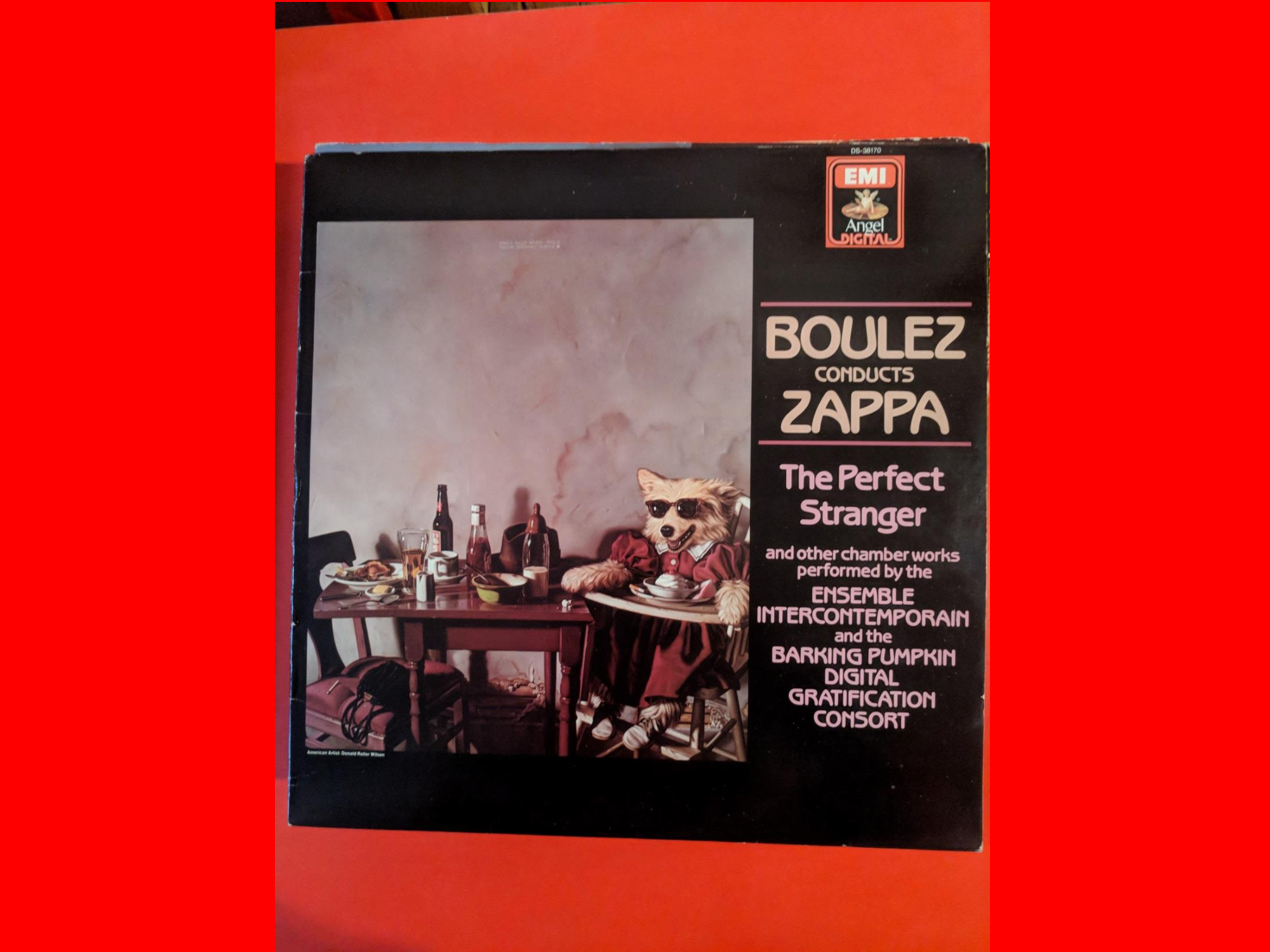

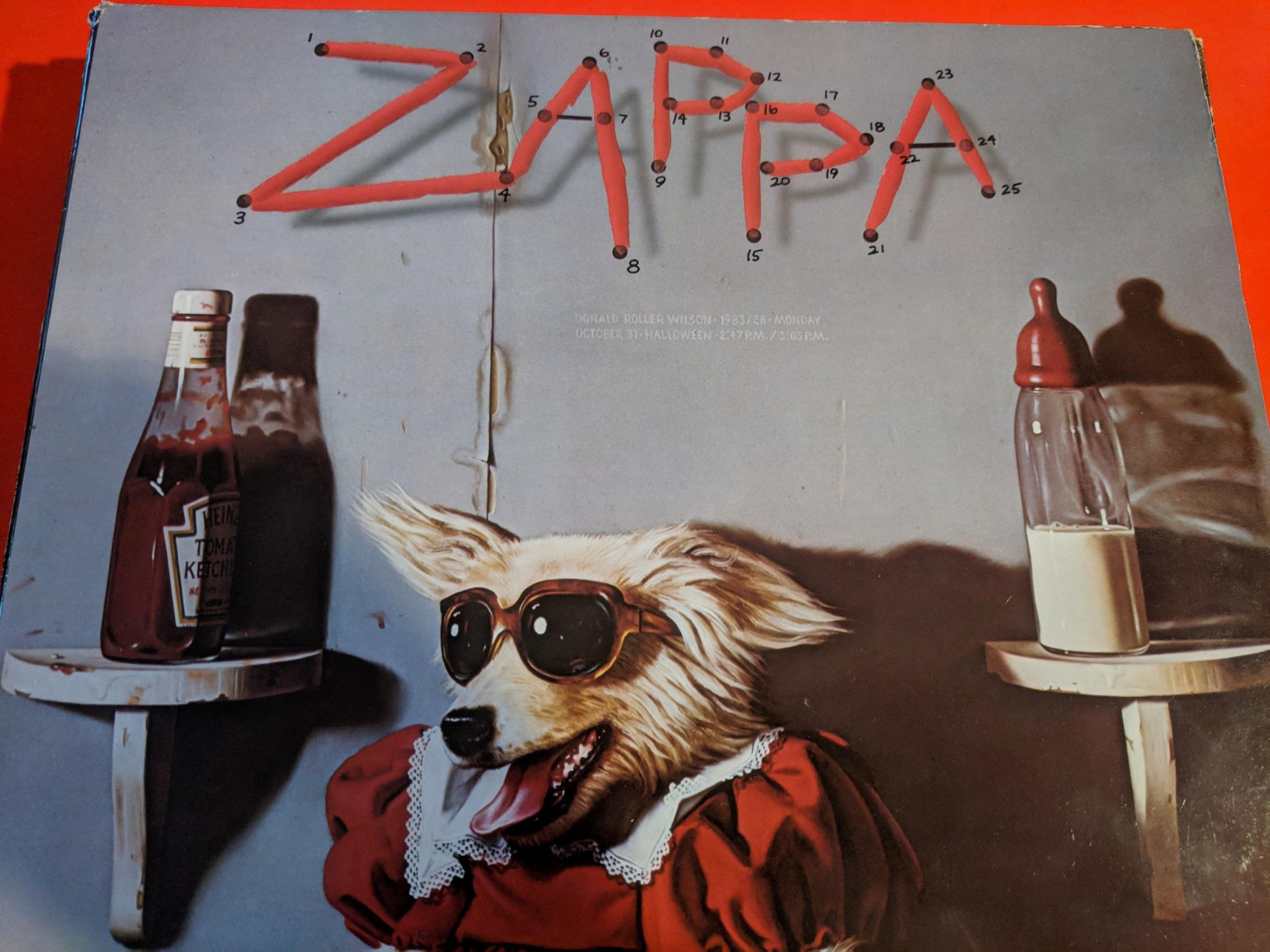

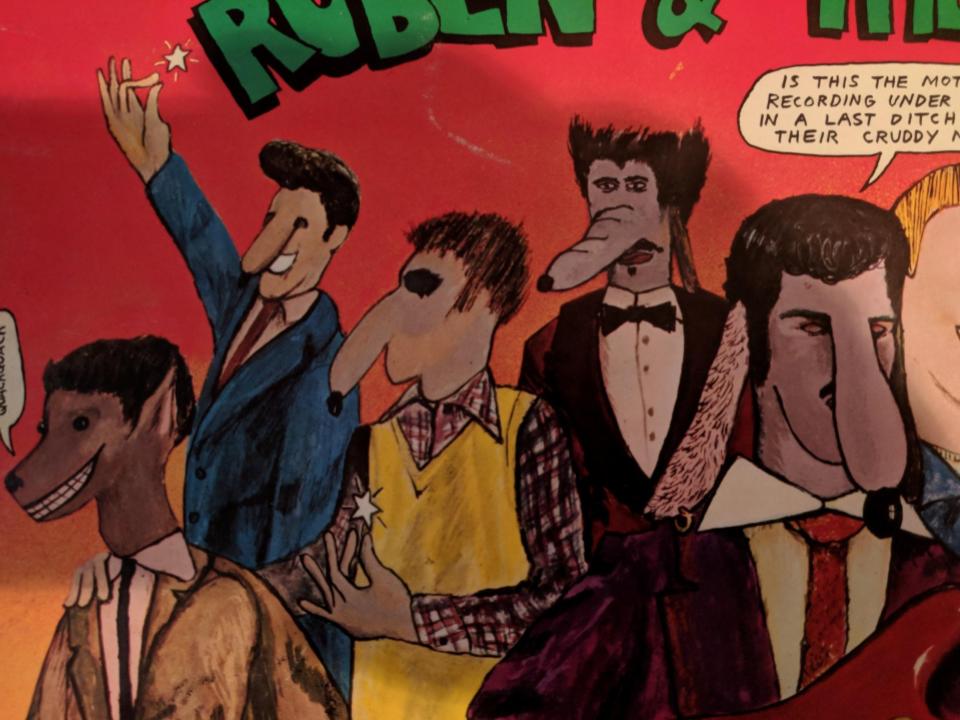

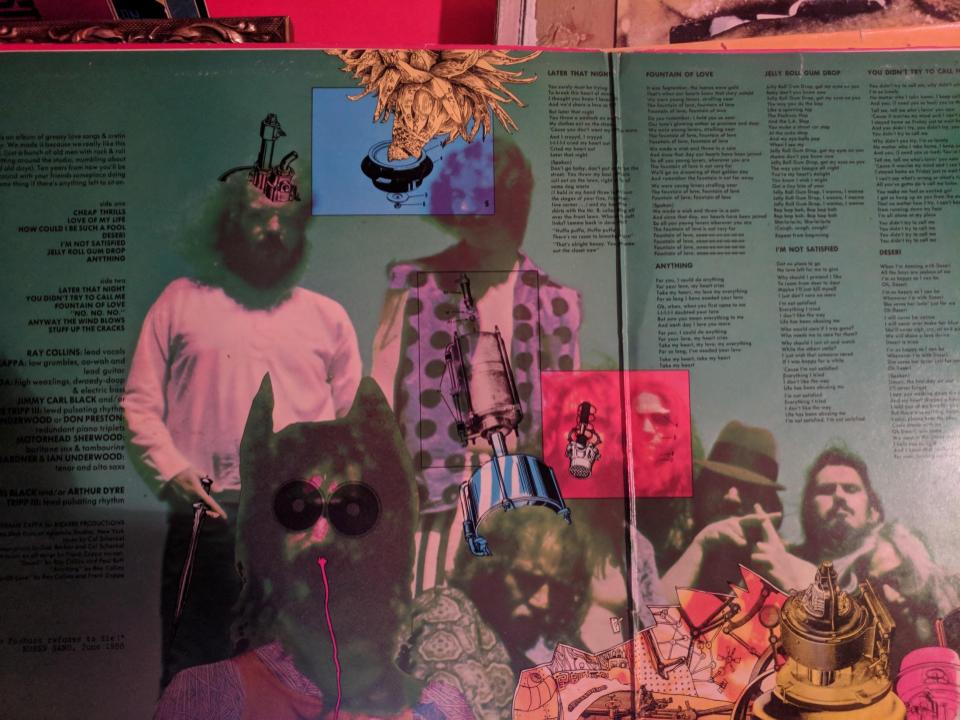

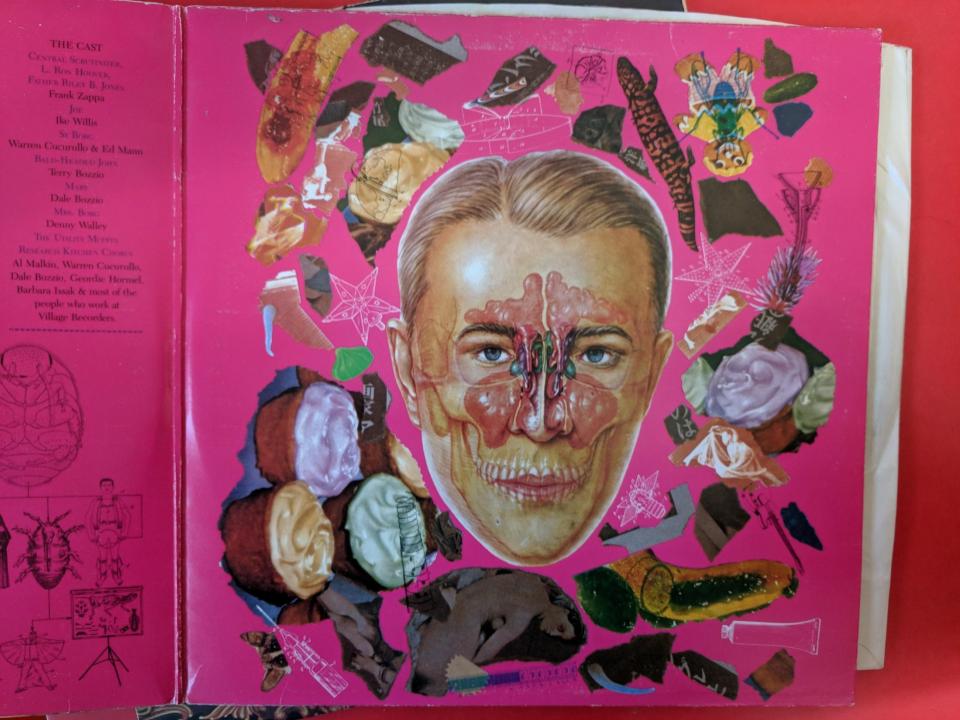

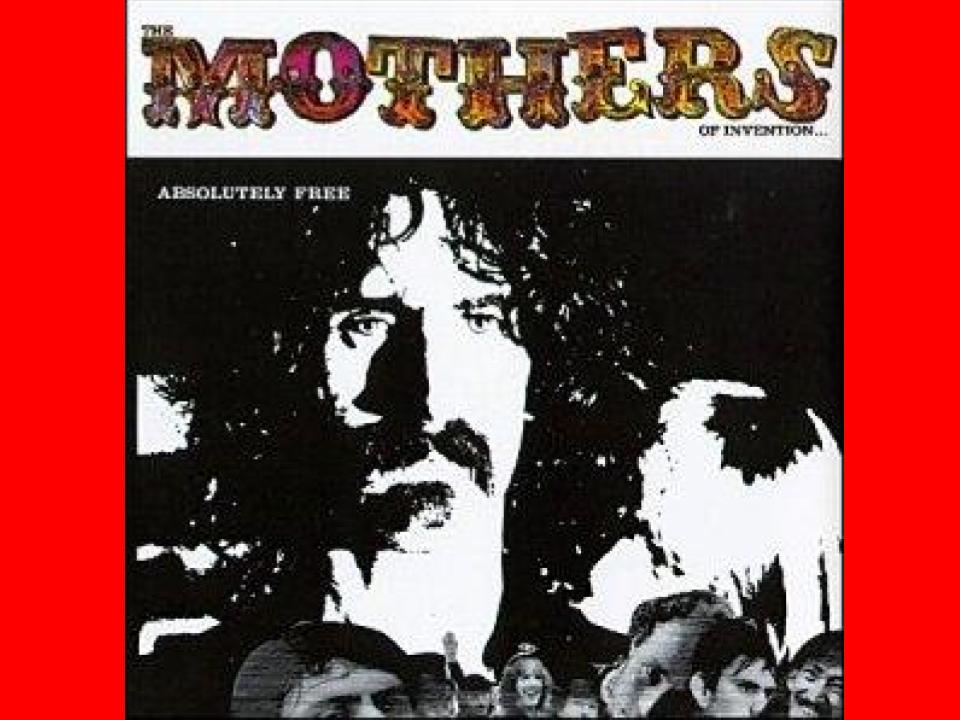

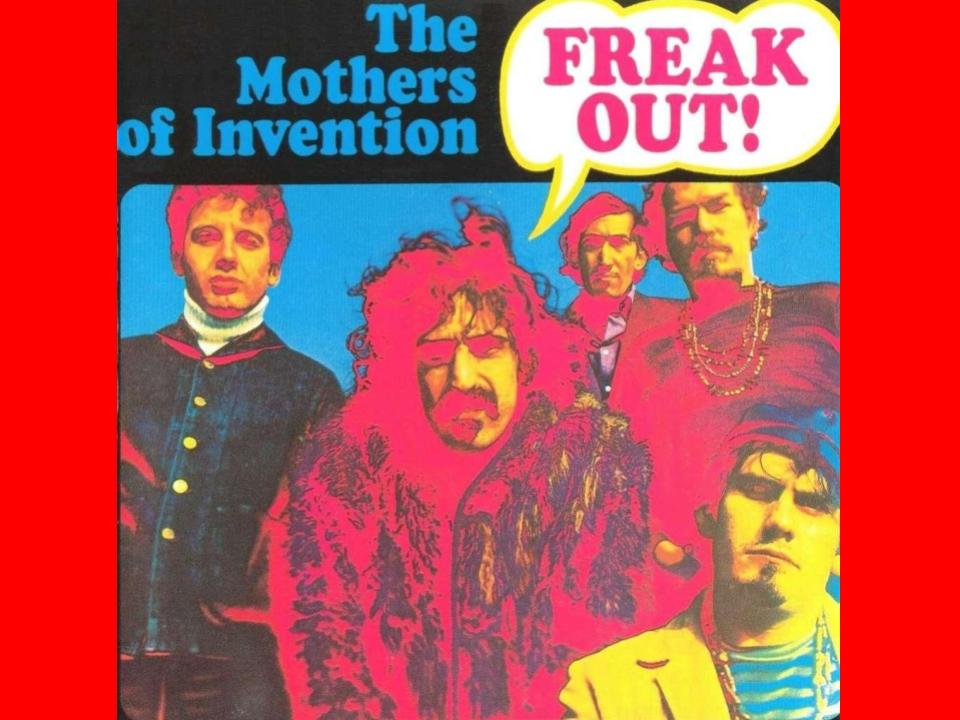

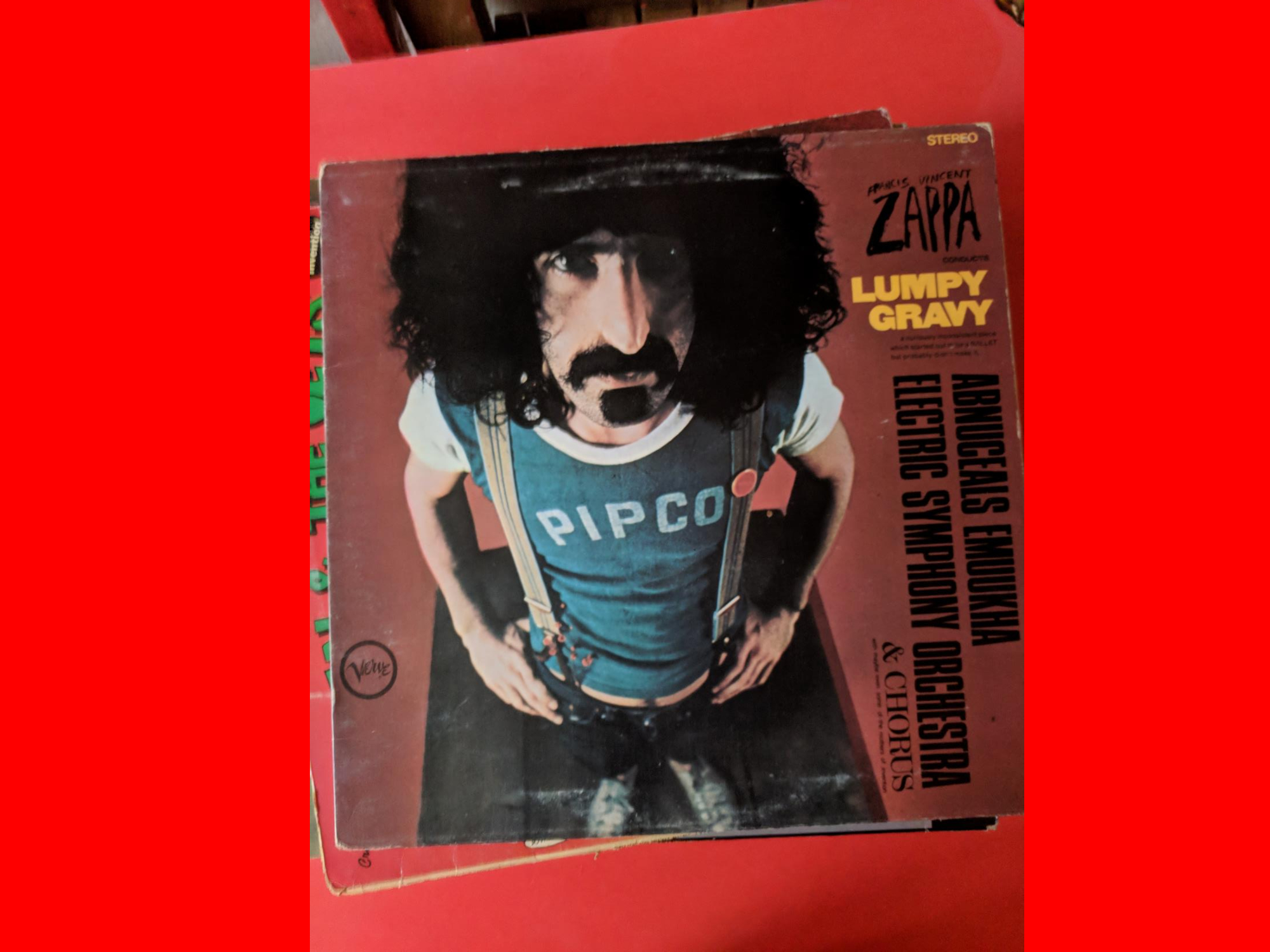

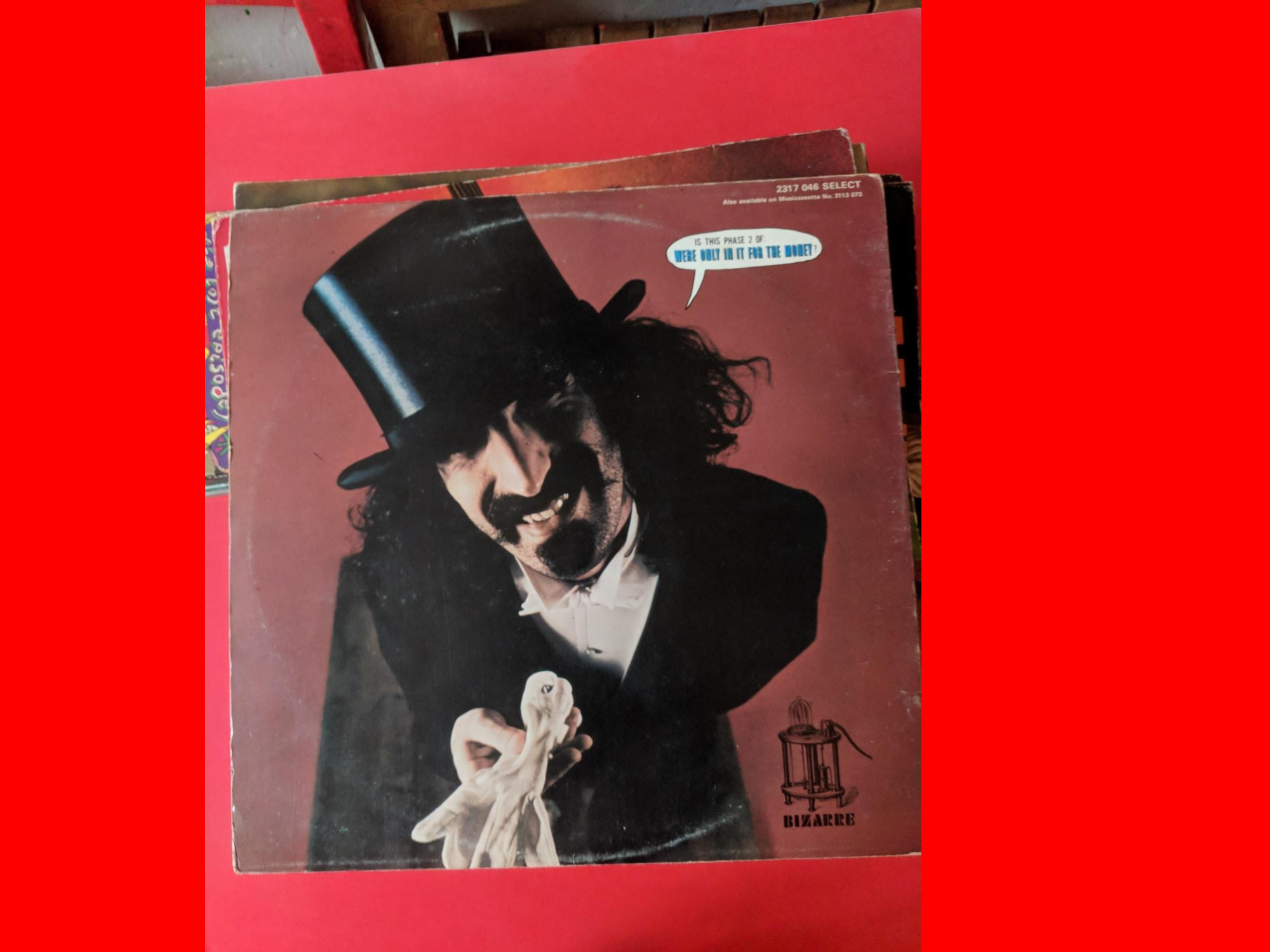

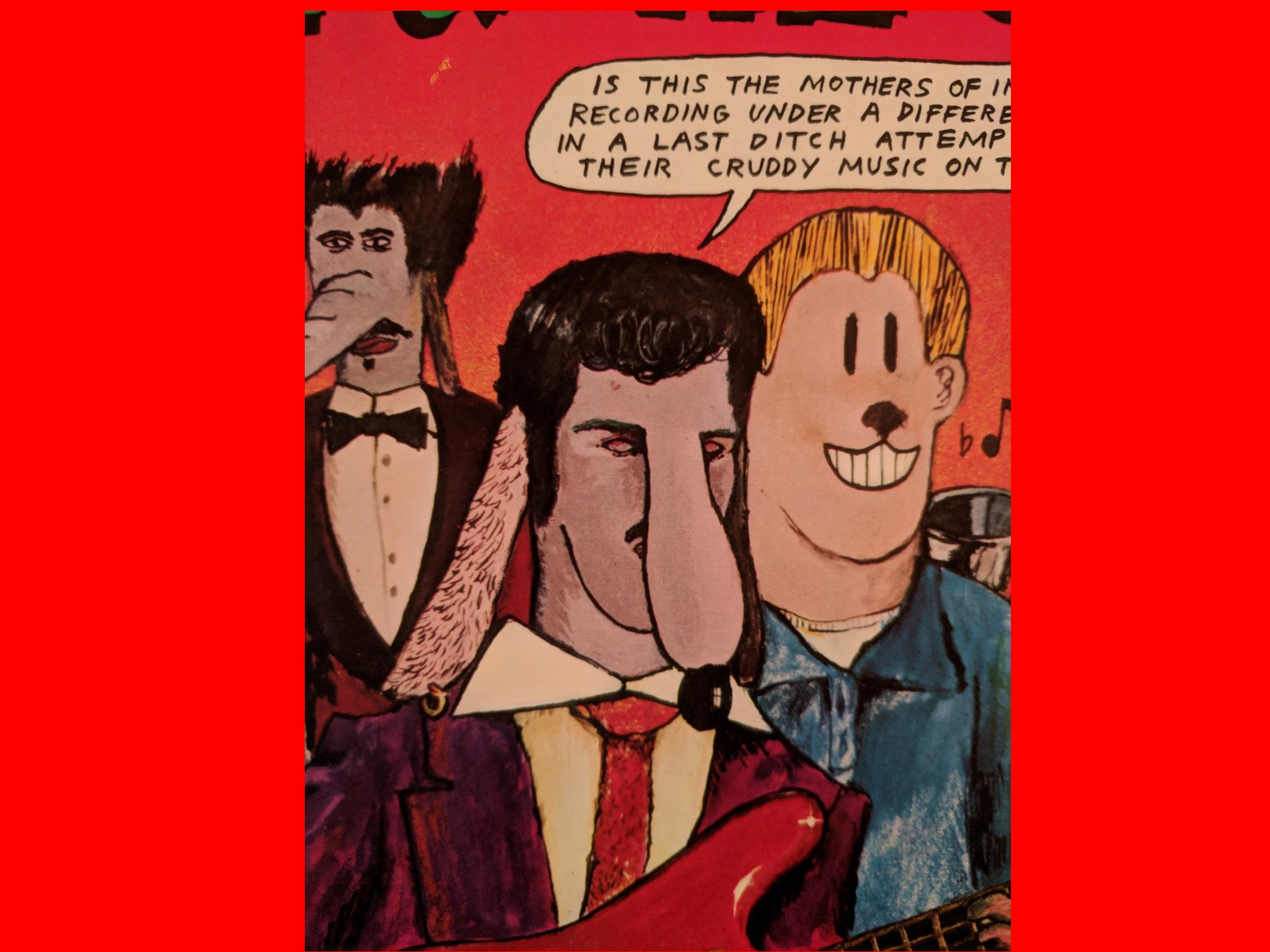

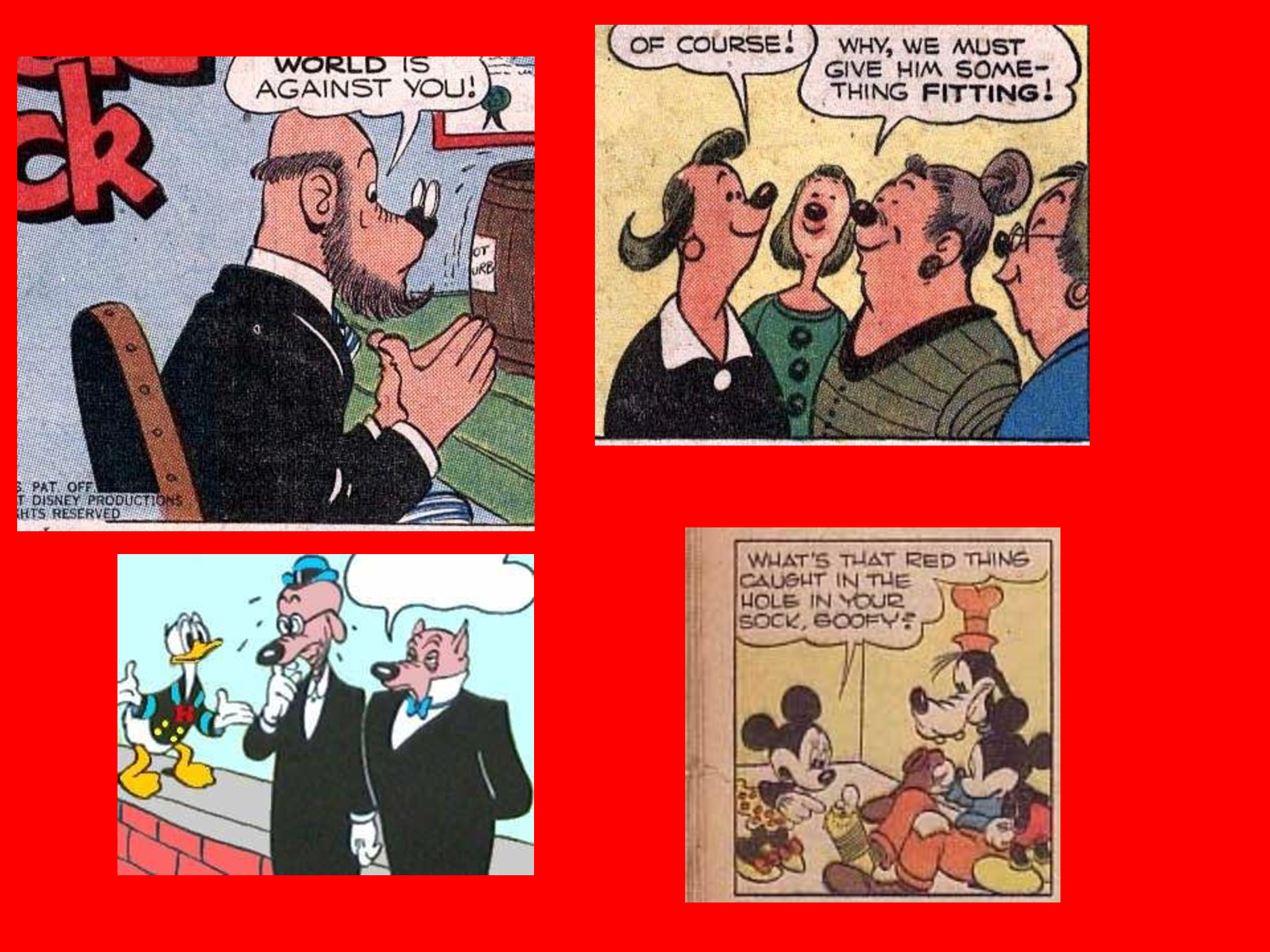

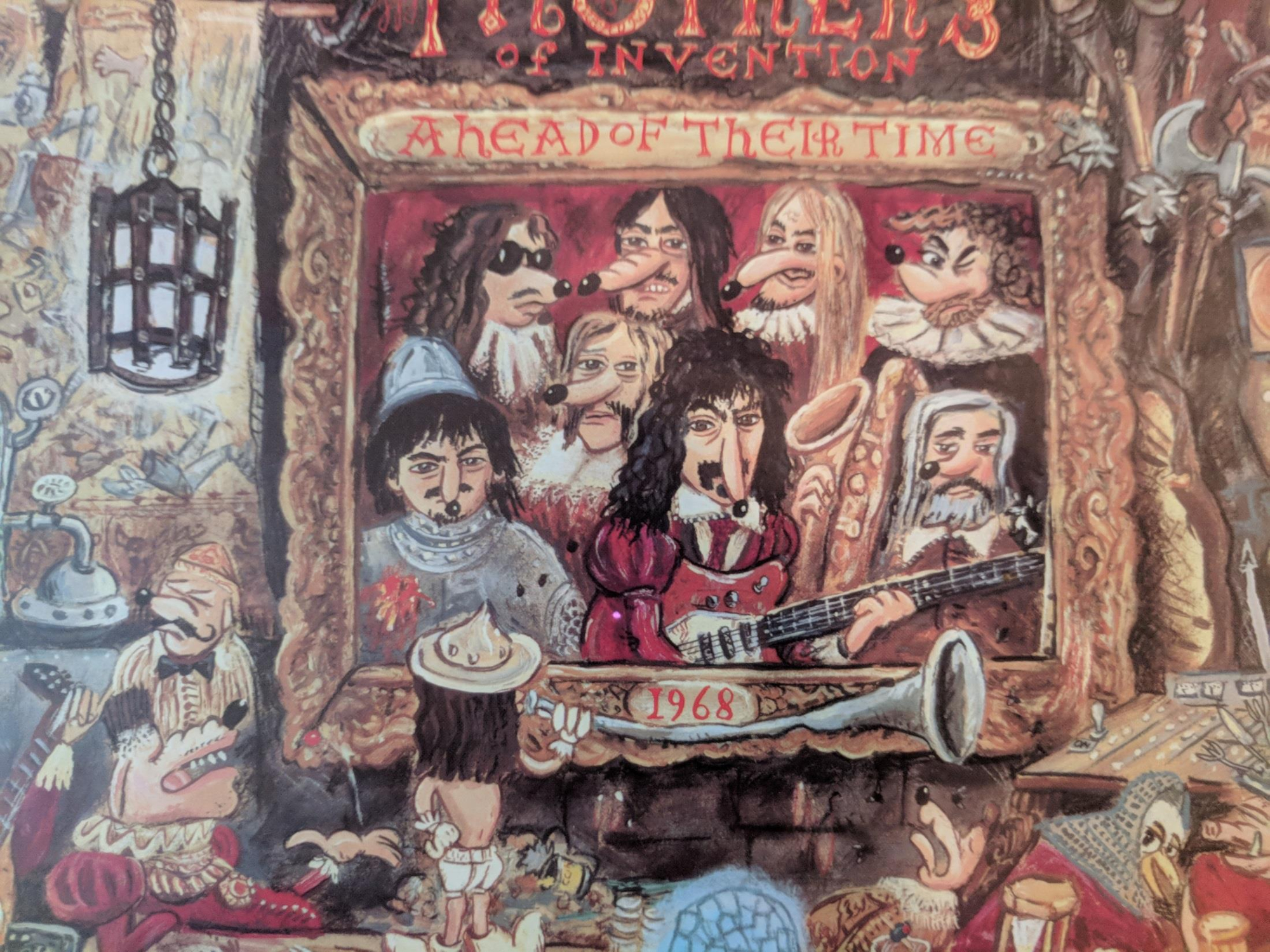

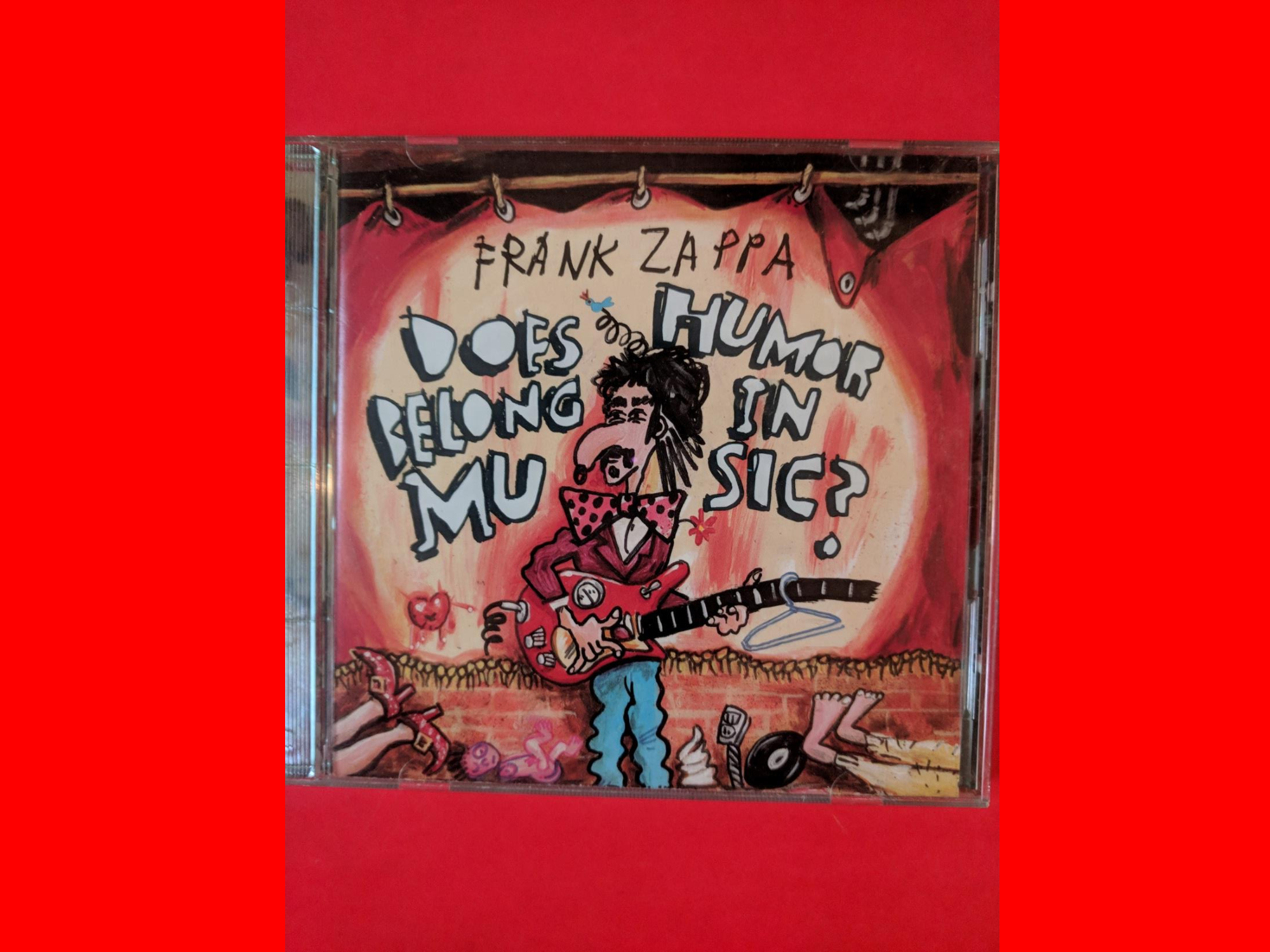

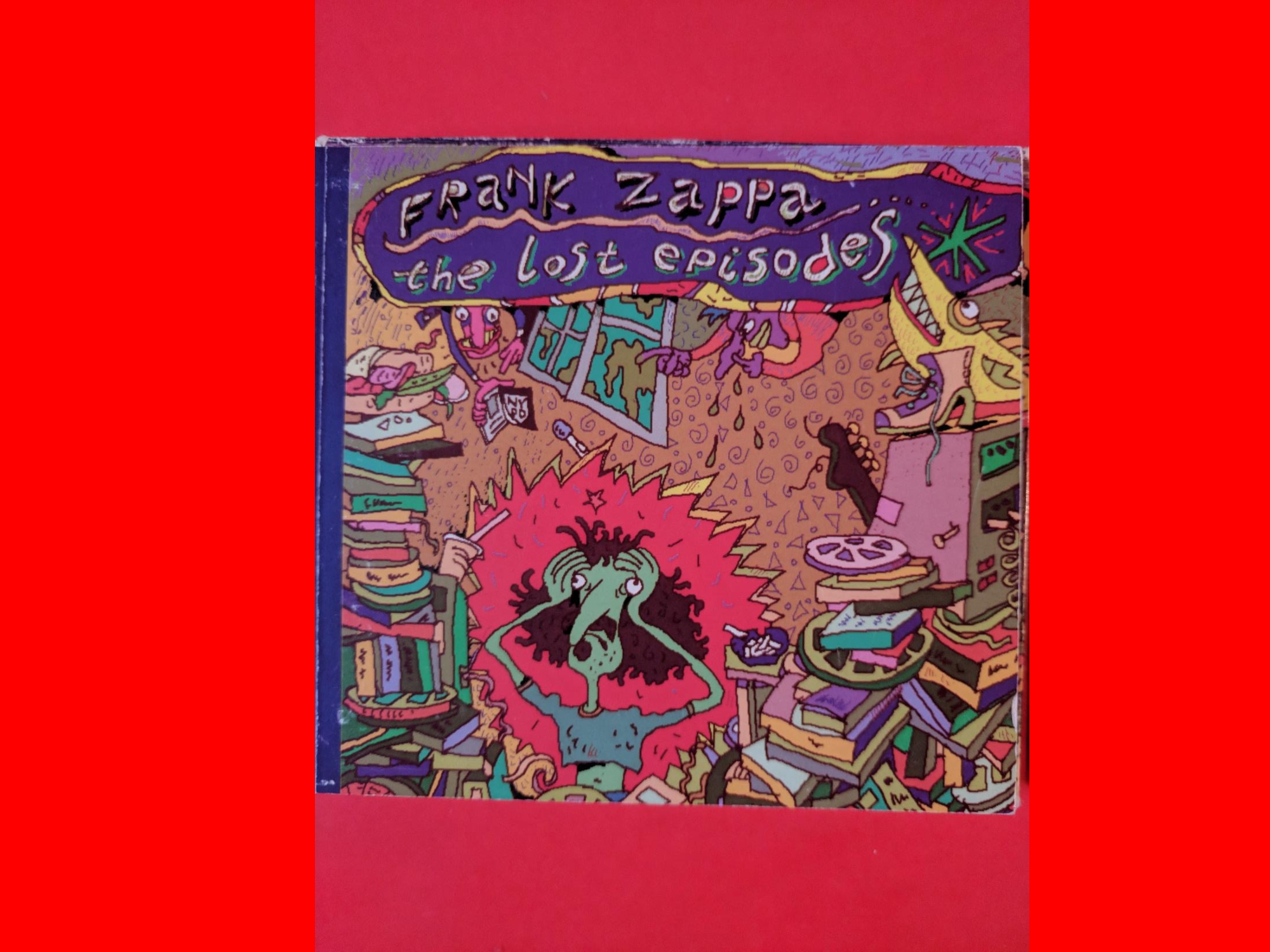

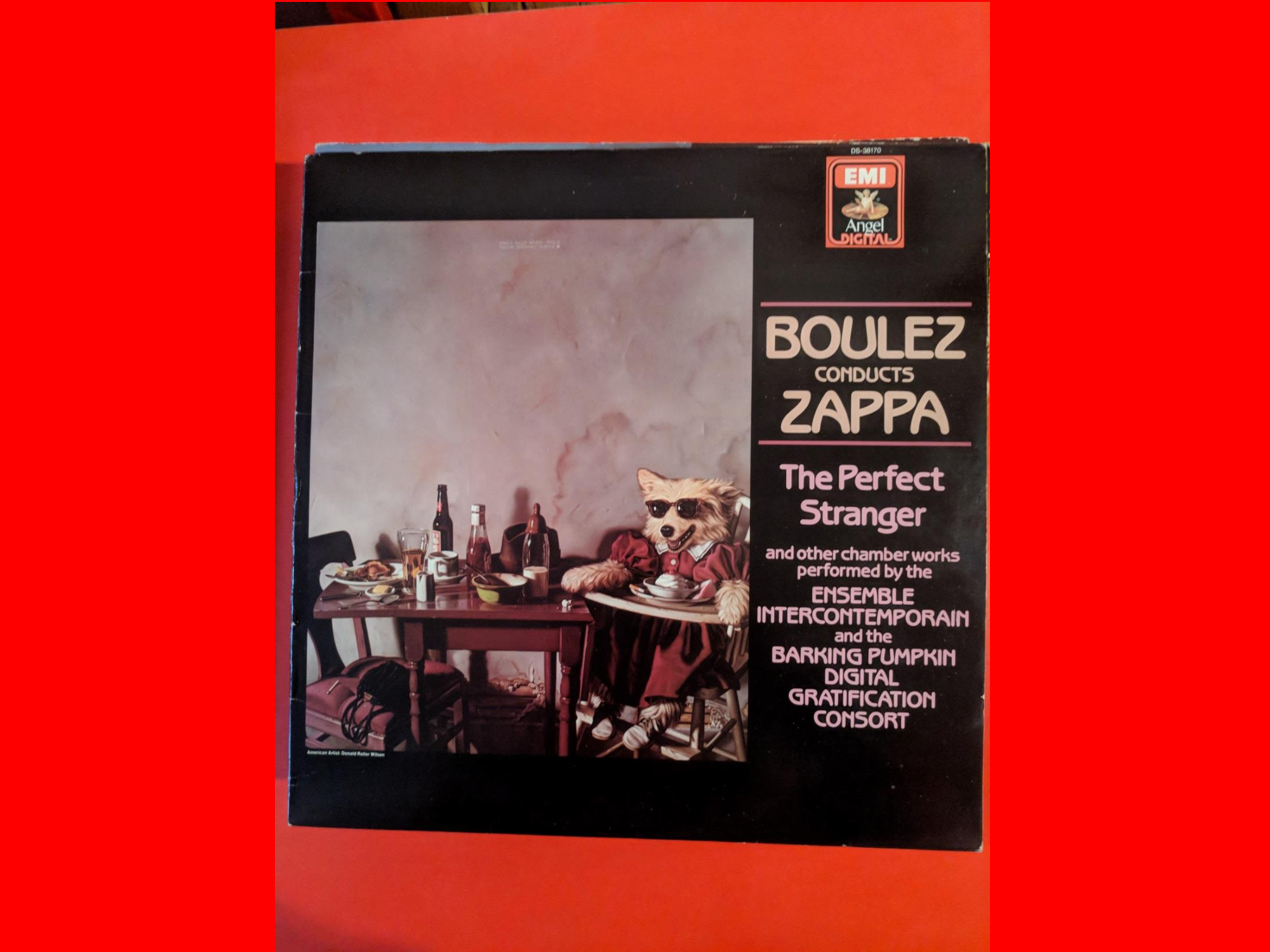

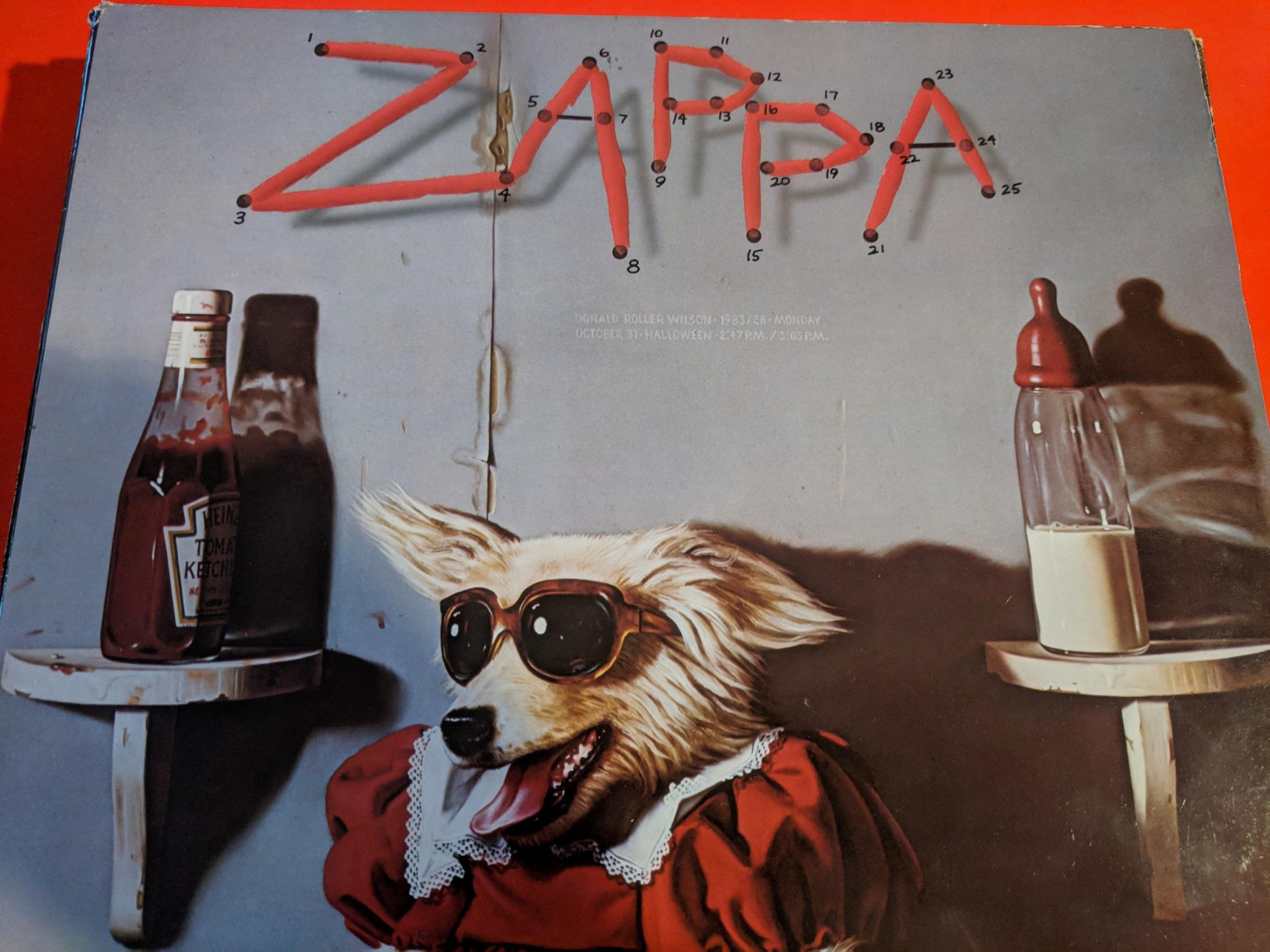

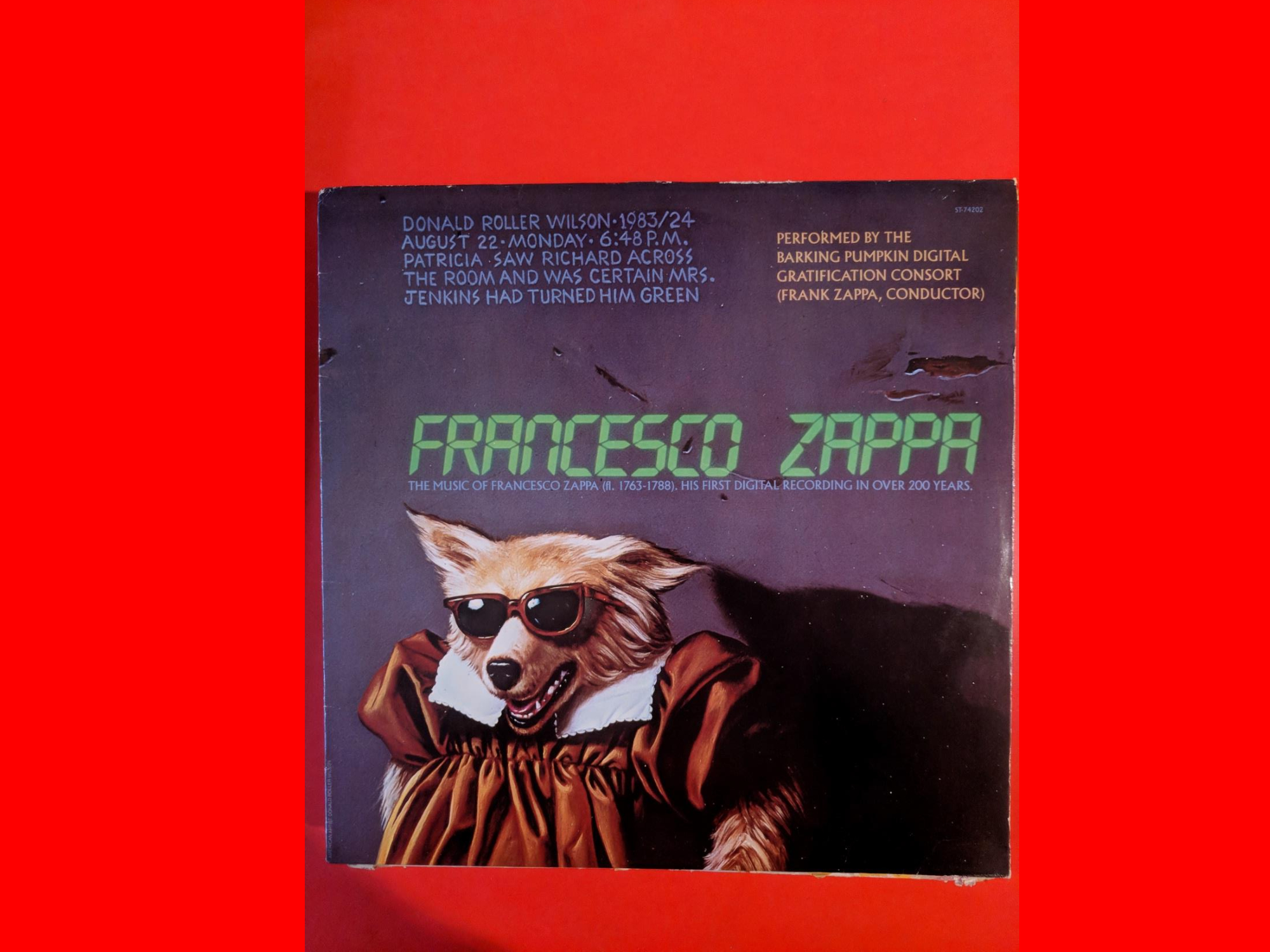

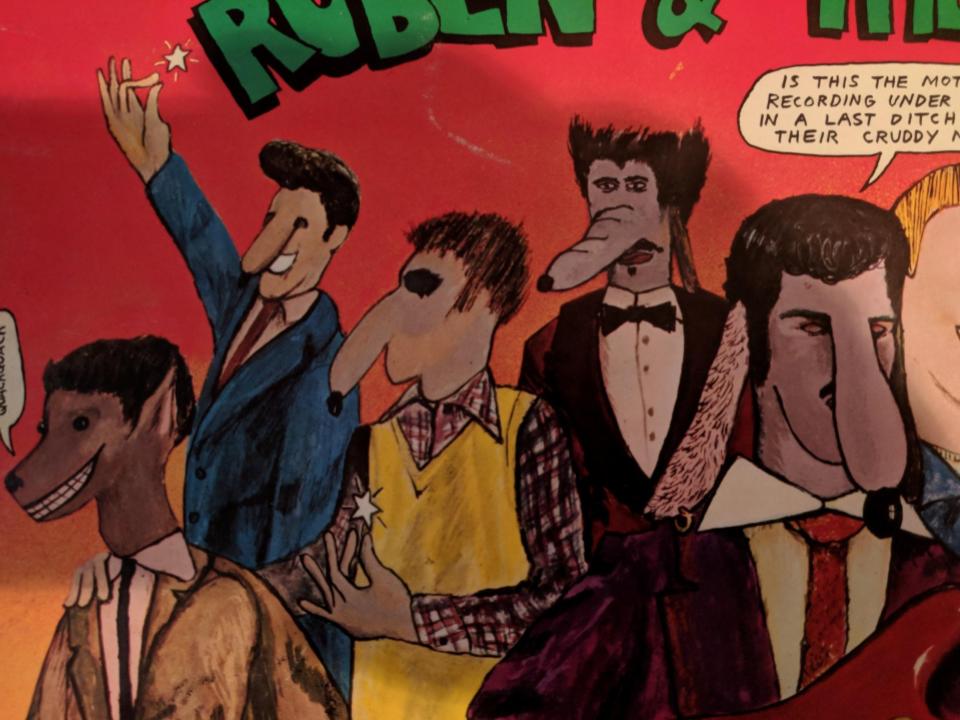

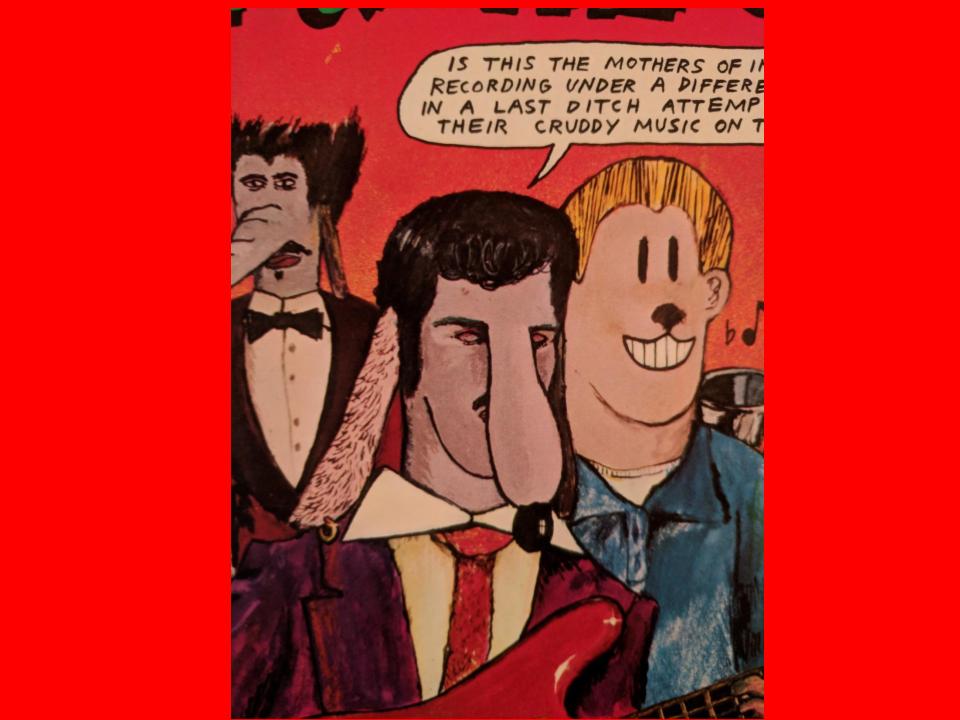

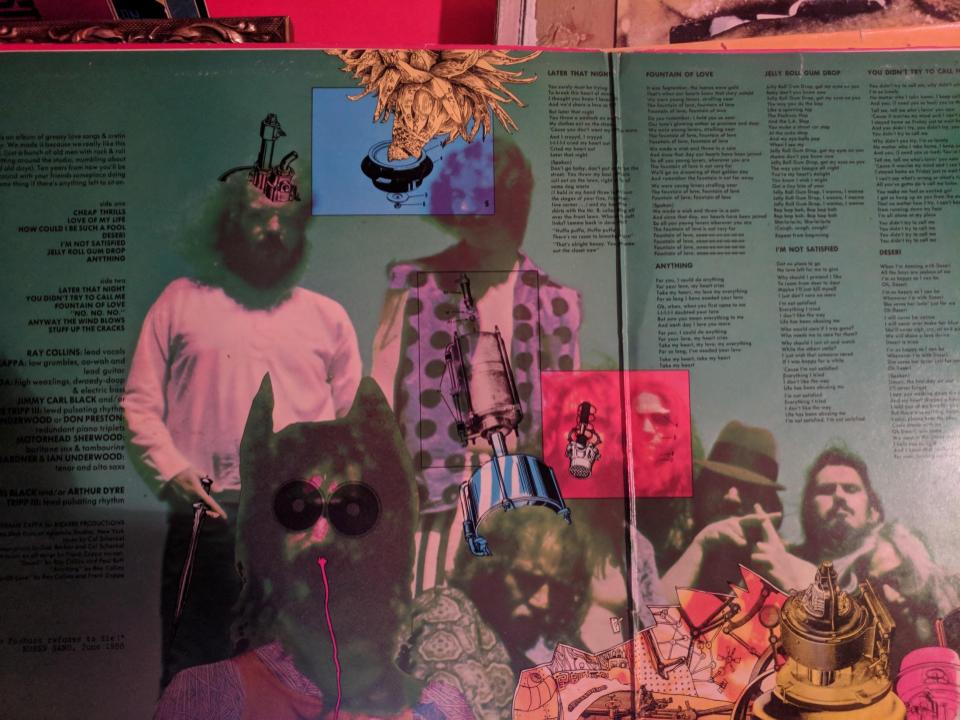

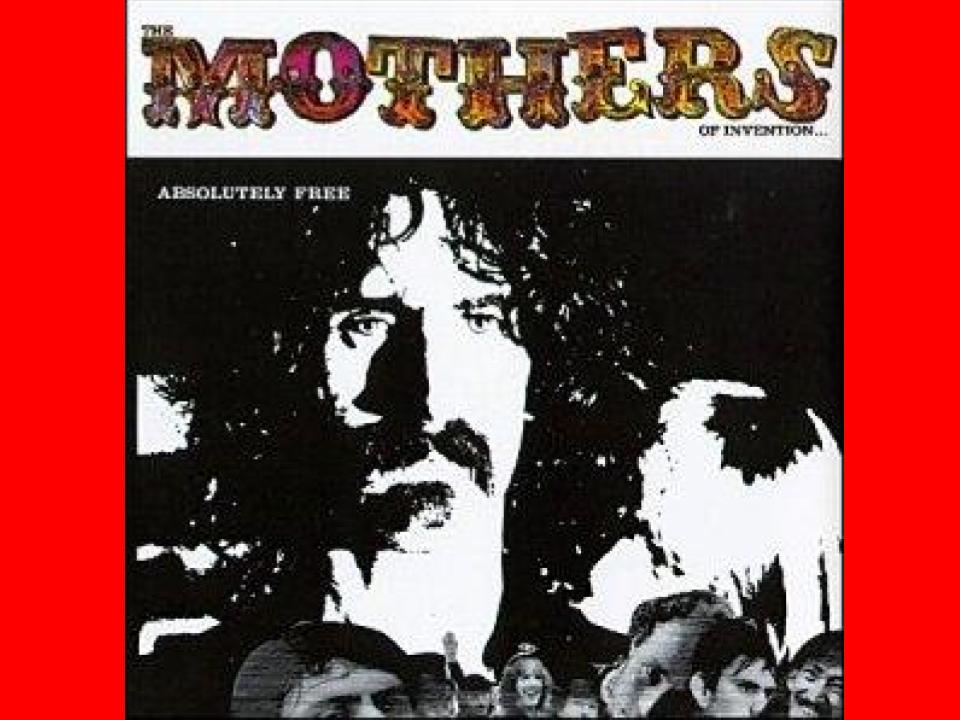

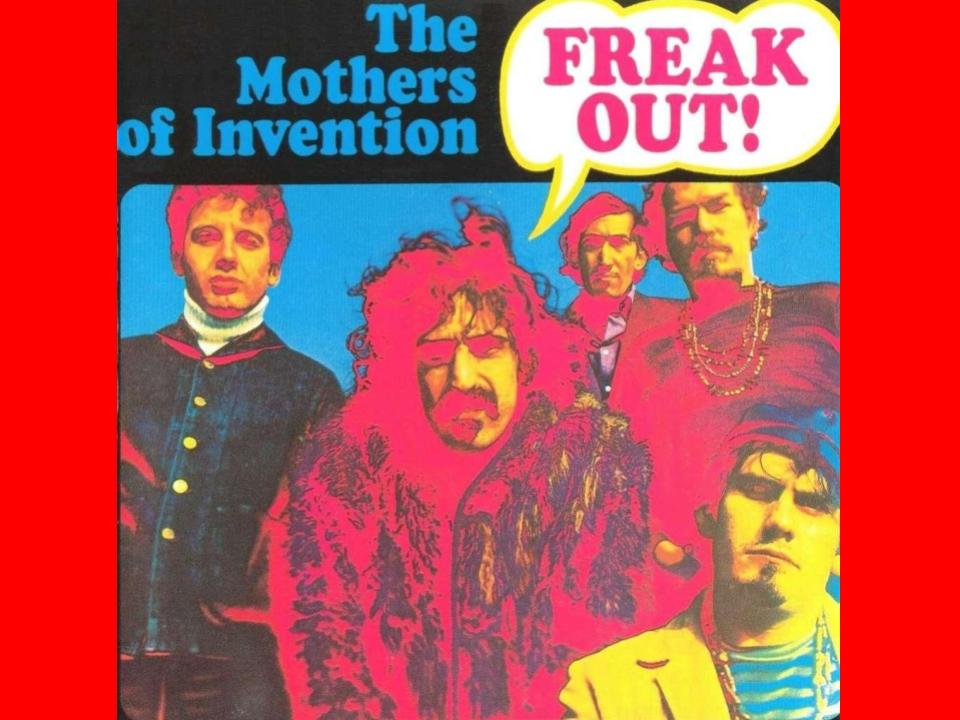

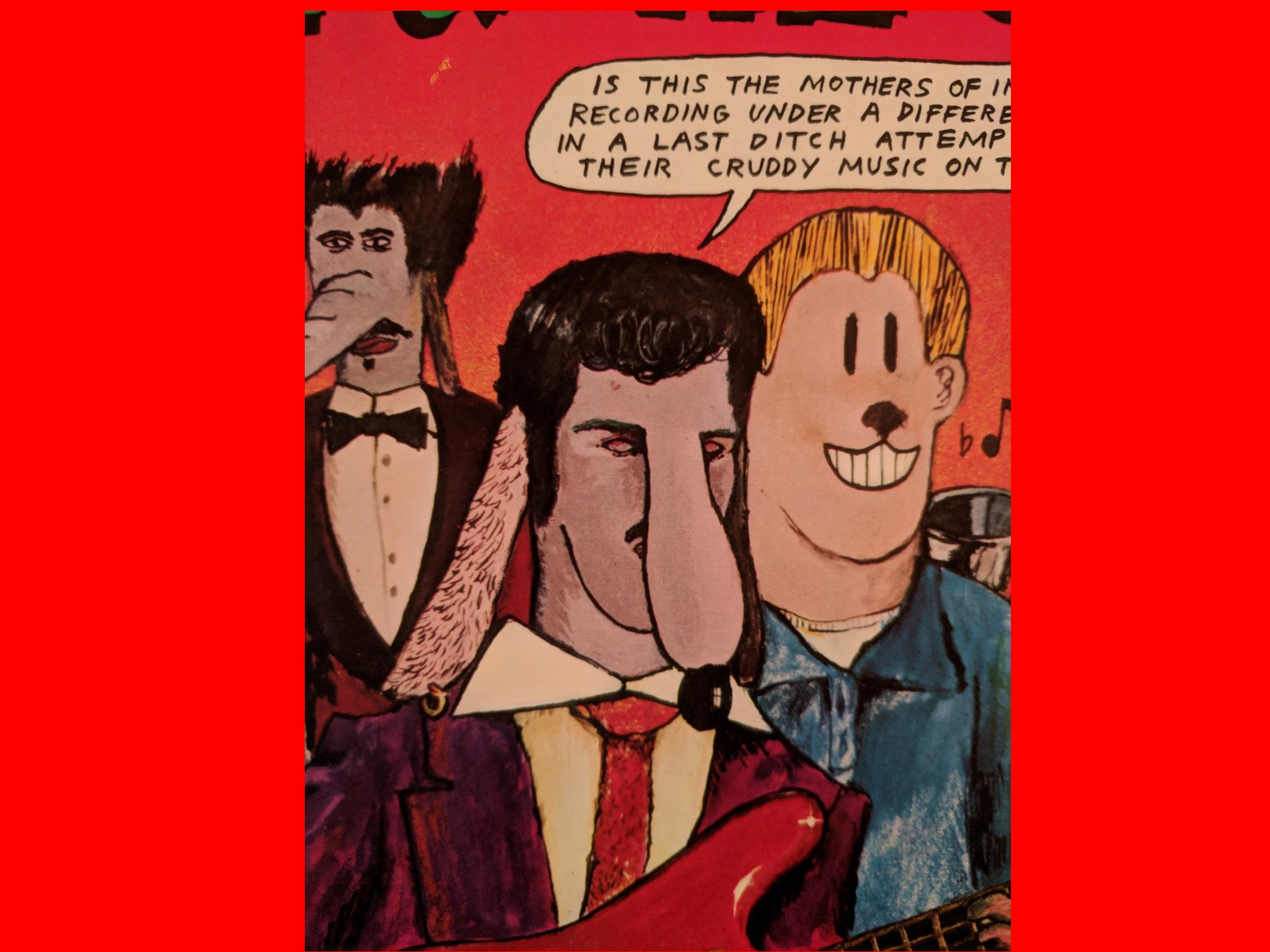

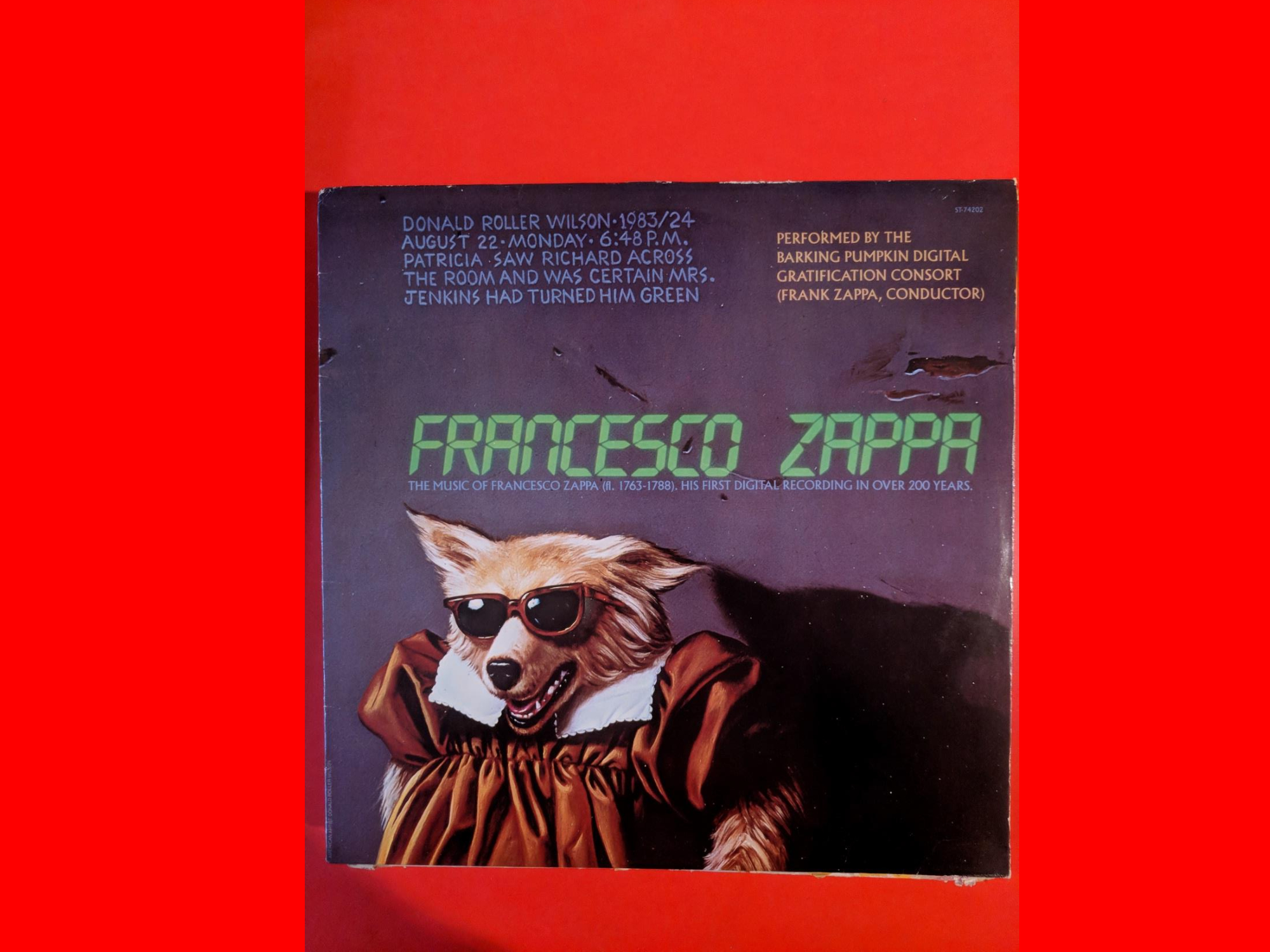

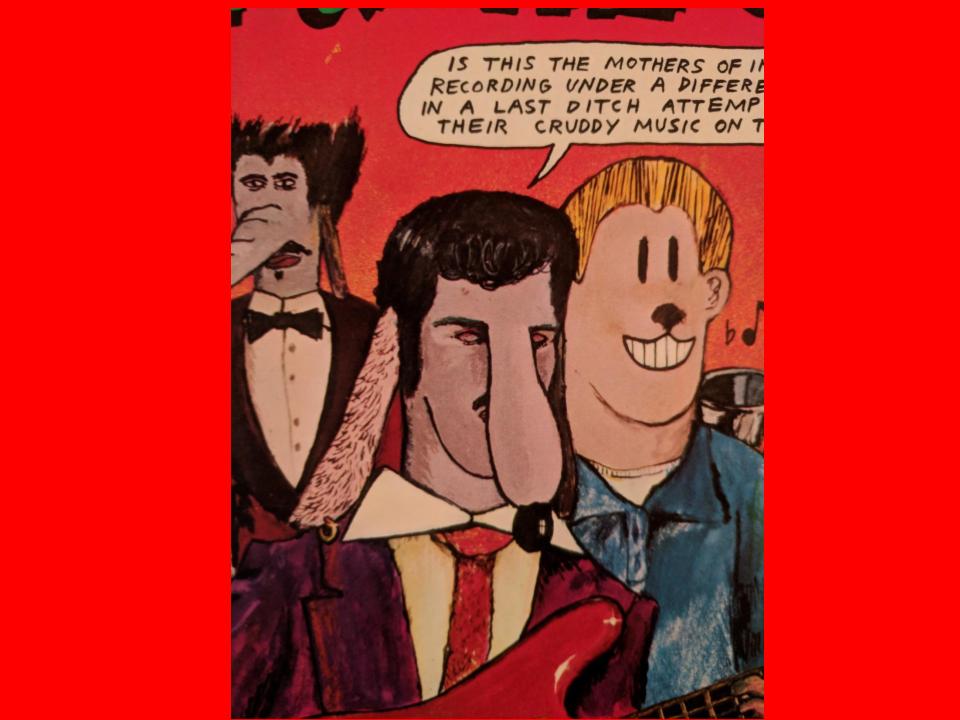

There are two things that stand out on many of Zappa’s LP covers: dogs and noses. Lumpy Gravy’s 1968 Verve reissue cover, put together by Cal Schenkel, foregrounds Zappa’s nose. One side is photographed from above to emphasise the composer’s large nose. On the other side, his eyes are obscured by the brim of a hat, his lower face covered in dark hair, but donating a smile that thrusts his nose forwards. On the inner sleeve lurks a little dog with a long droopy nose. This kind of dog reappears on the cover of Cruising with Ruben & the Jets (from 1968), for which Cal Schenkel borrowed the dogface style from Disney artist Carl Barks, in order to intimate the animal and infantile instincts, or ‘cretin simplicity’ and ‘lewd pulsating rhythm’ of rock and roll. Schenkel borrowed the dogface again in 1972’s Just Another Band from L.A., in 1993 on the live album Ahead of their Time and in 1995, with the reissue of Does Humor Belong in Music? To show the promiscuity of this sign, it should be noted that The Simpsons’ animator Gabor Csupo used it on the posthumous The Lost Episodes in 1996. A different anthropomorphism appeared on Boulez Conducts Zappa: The Perfect Stranger from 1984. Zappa licensed images from American artist Donald Roller Wilson. These featured a dog called Patricia, sat like a toddler in a highchair, surrounded by items of Americana, including Heinz ketchup and Budweiser beer, as well as a baby bottle and a breast-like pie of cream topped by a cherry. Patricia appeared on two more albums from 1984: On Them or Us, the dog is flanked by sweet liquids ketchup and milk. Zappa’s name is spelt out draw-by-numbers style, to underline the infantilism of the scene. On Francesco Zappa, her white bib and brown velvet dress are a hint at the eighteenth century attire of its subject composer, and this is montaged with LCD writing, an indication of the synth modernity the music was refracted through.

The nose, Zappa’s nose leads to a dog, a dog nose. Zappa has a dog’s nose, the dog’s nose sneaks across the covers, spreading a cartoon and comic book aesthetic that appears through the decades. Or the dog and its nose, or snout, is compromised by its location at one and the same time in differing worlds, the childish world of industrial pap in the nursery and the highfalutin’ world of classical music. The childish world relishes body experiences, for it has not yet adopted the life of the mind, nor bodily repression. The classical world has a body too, a selective one, for it is typically described in relation to facial parts such as high brows and the disdainful features of snooty types who look right down their noses. This body is a distanced body – a high brow sign of a huge brain, or cultivated mind; their noses cocked in horror are noses that do not smell, noses that are distant – protected - from the smelly location of crudeness. These brows and noses are signs of distinction.

Large sniffing noses and nosy dogs relate to lowness. But, as Zappa’s covers seem to suggest, the nose and the dog might really be one thing, or two things that stand in for one: the penis. Dogs and noses relate to that which sloughs off repression and autonomy. They relate to sex. Dogs are all instinct, low, unrepressed, sticking their supersensitive noses into all manner of places without shame. Noses are about stink. Philosophers, such as Kant, whose systems outlined emergent repressive bourgeois civilisation, wished to do away with the nose, to abolish smell, for the nostrils had no choice but be suffused by odours, which compromised the sovereign self. The nose is only a small part of the whole human, but it is often the part that most defines them. Zappa knew this well, being often defined in the rock press by his nose.

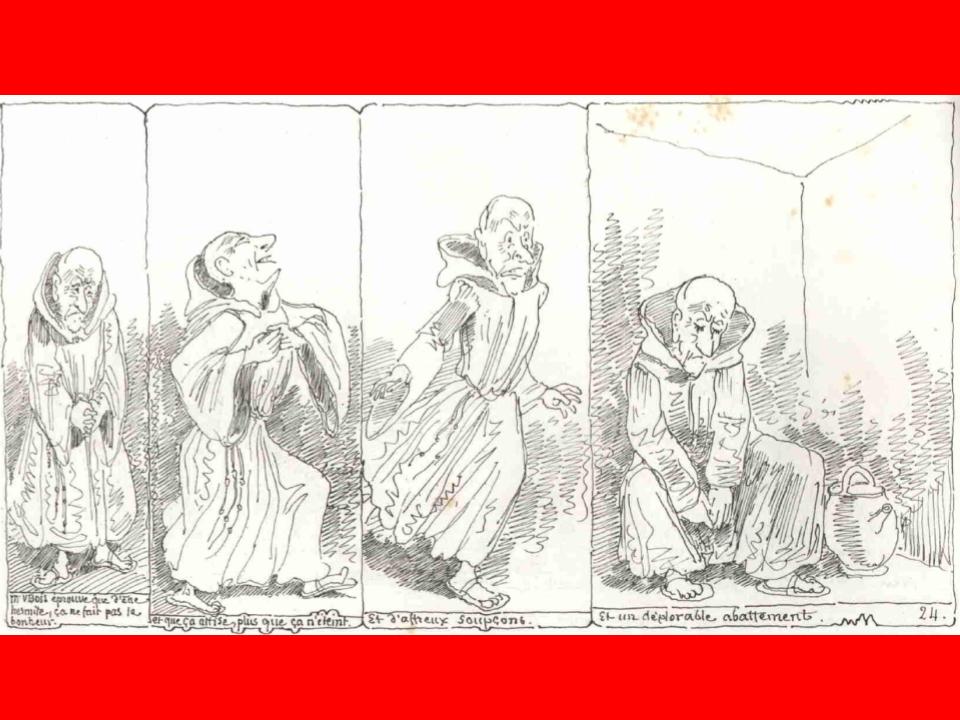

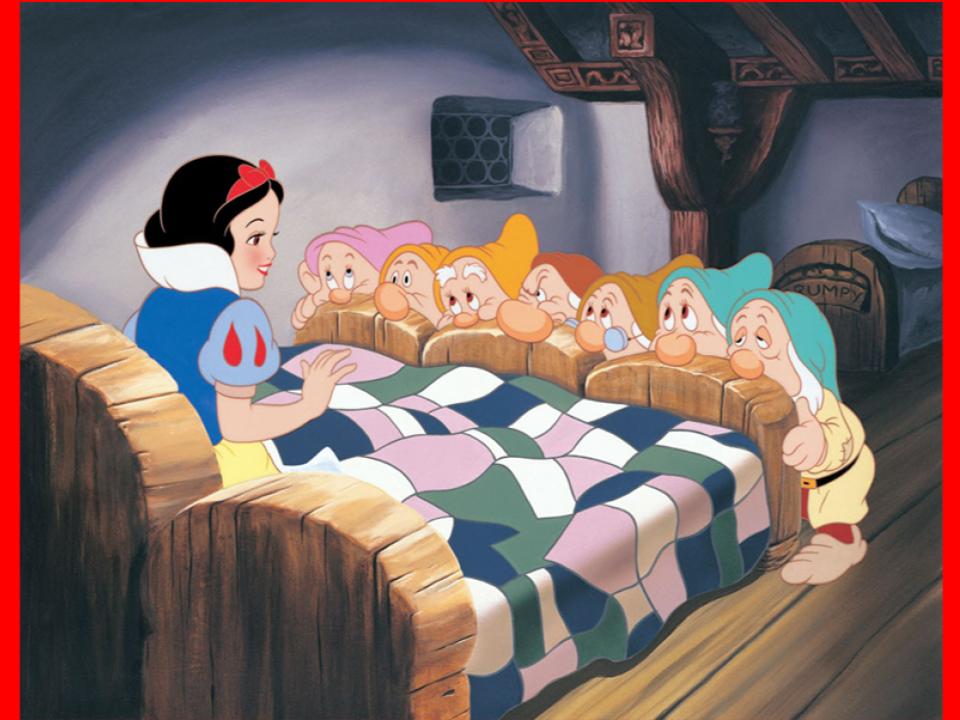

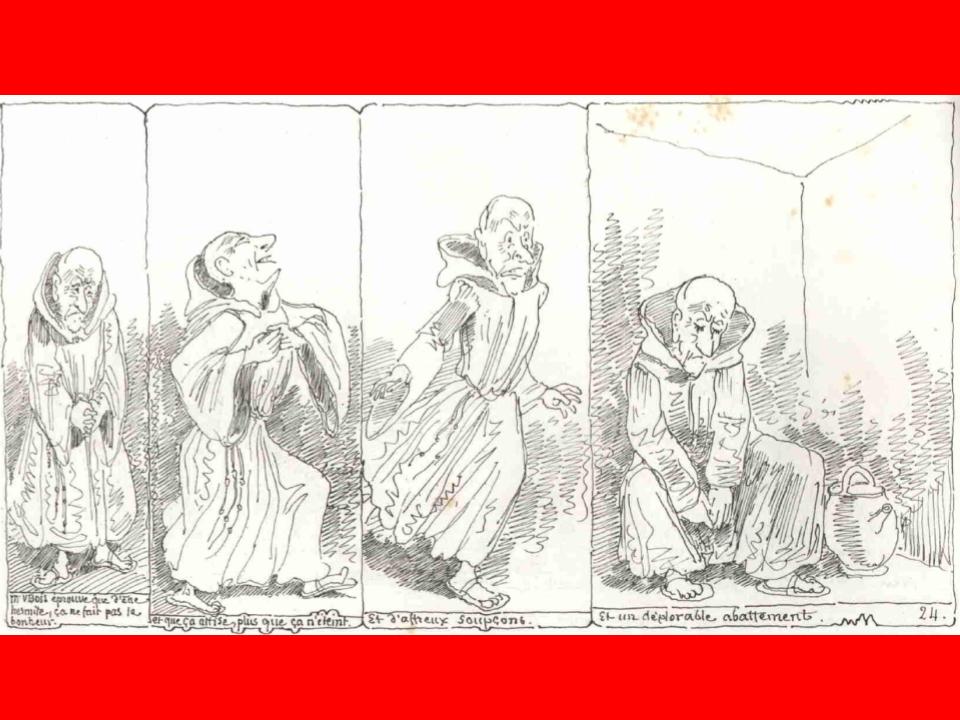

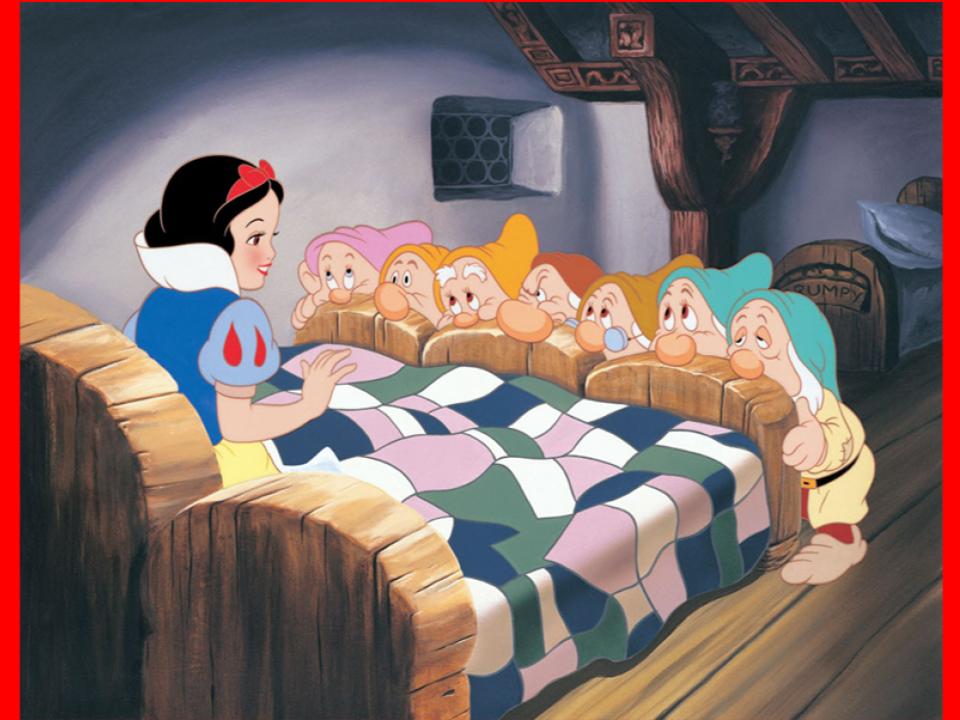

In the scale of things the differences in nasal architecture are fairly small, but these small differences are what form the basis of caricature. Swiss experimenter Rodolphe Töpffer is reputed to have invented the genre of bandes dessinées in the mid-nineteenth century. Töpffer produced little albums of continuous strips, with characters in whimsical, nonsensical plots. Sometimes his strips plotted transformations of an object, for example, a face. This served as an object lesson for the animation that followed from the end of the century onwards. The animators of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs used Töpffer-like variations in the shot of the dwarfs at the end of Snow White’s bed, their noses drooped over the bedstead, each face a little different from the others. The differences are small but significant, defining each dwarf as specific as well as general. In their variety lies a humour. But these Disney noses are also phallic, and they hint at a relationship between the dwarves and Snow White that is nowhere to be found on the saccharine surface of Disney’s animated feature. The animators were, of course, much more worldly than the innocent fare they were paid to produce might suggest. It is the same nose/phallus equation made in the portrayal of Ruben & the Jets.

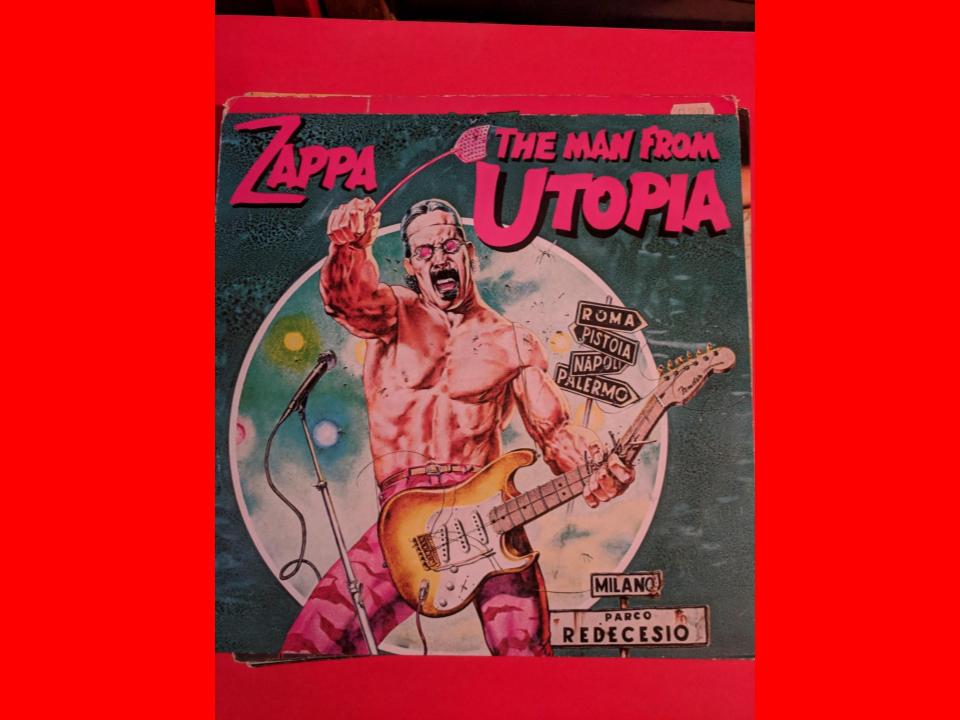

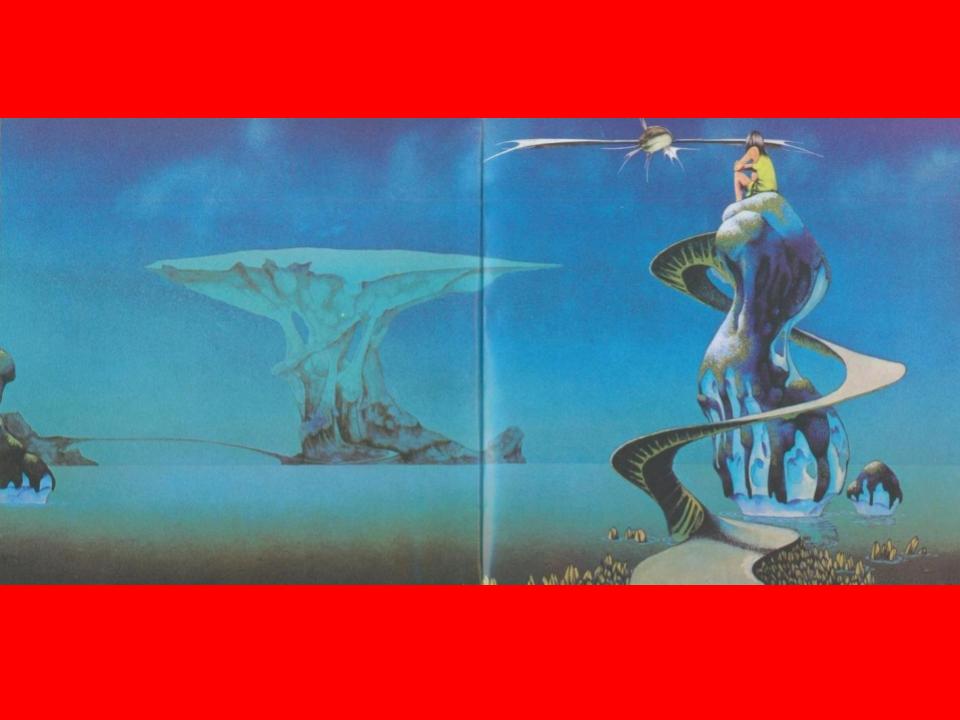

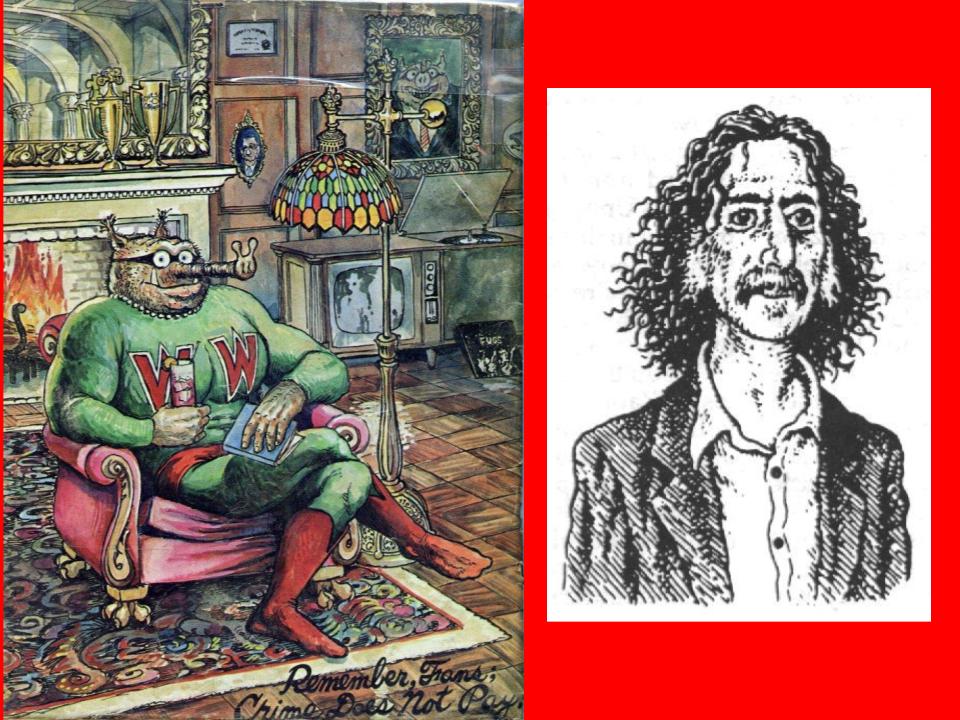

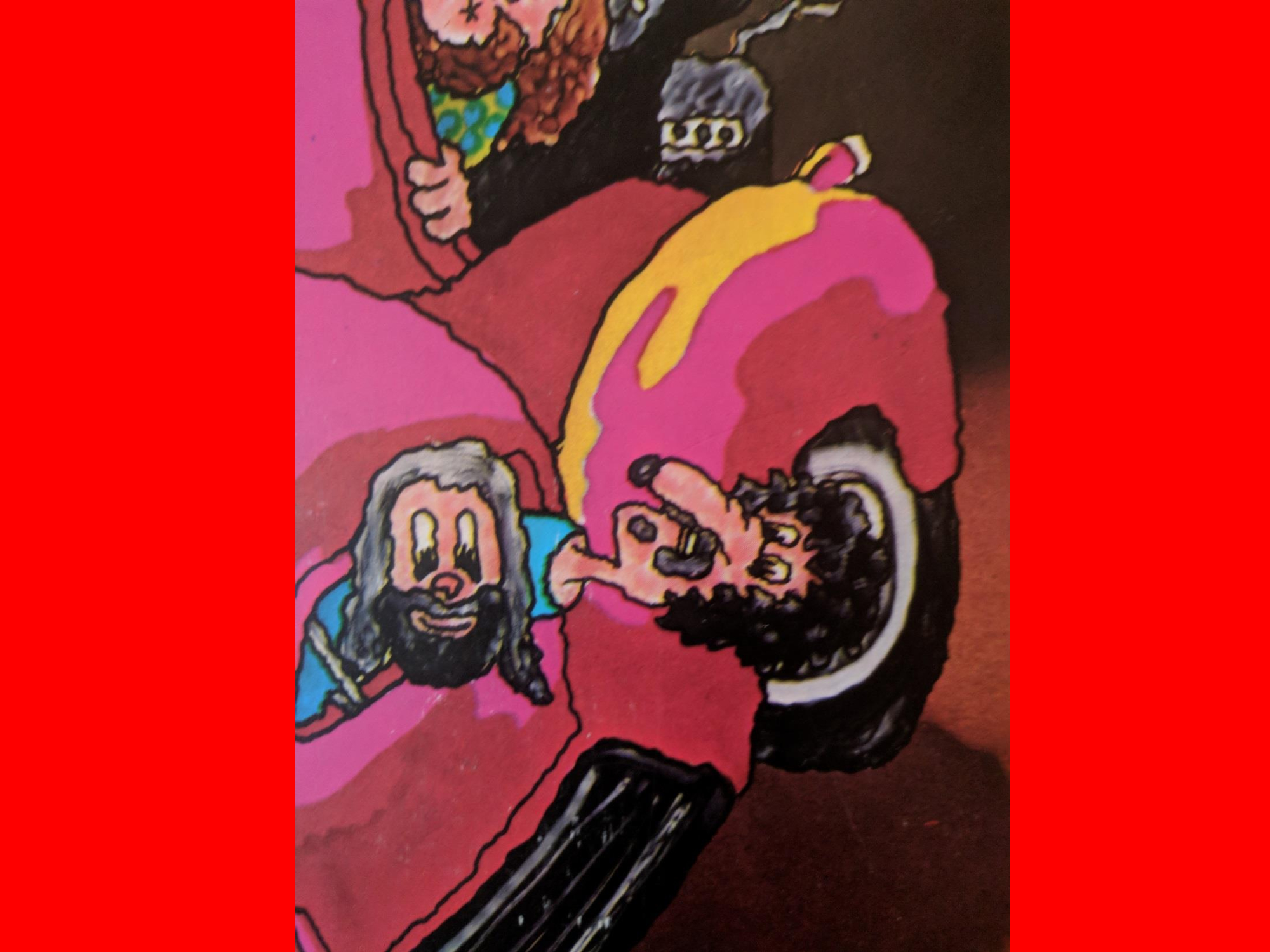

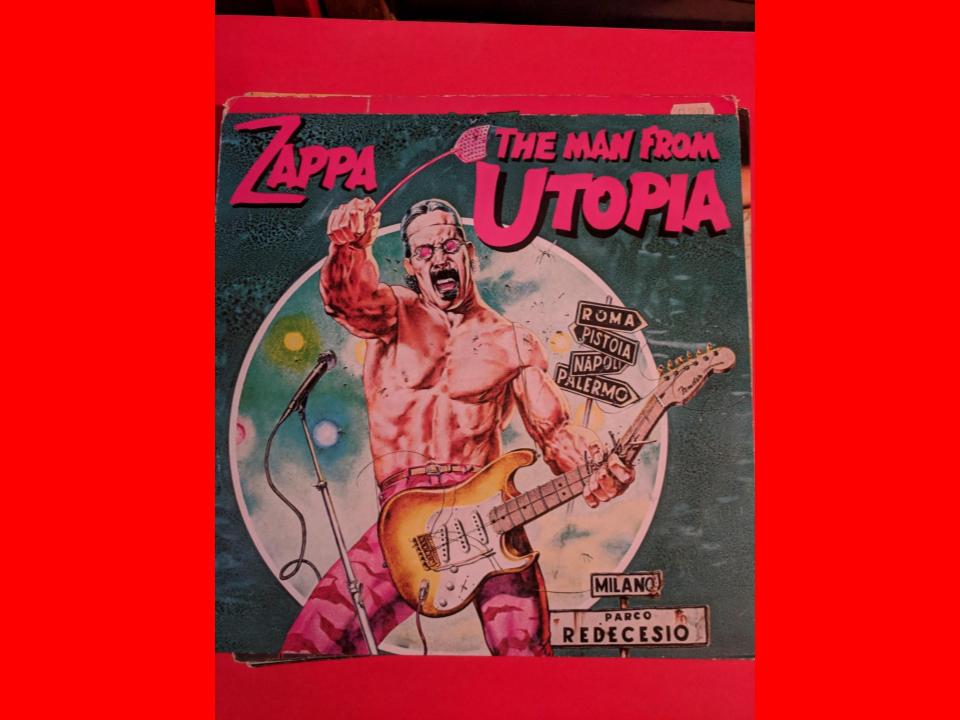

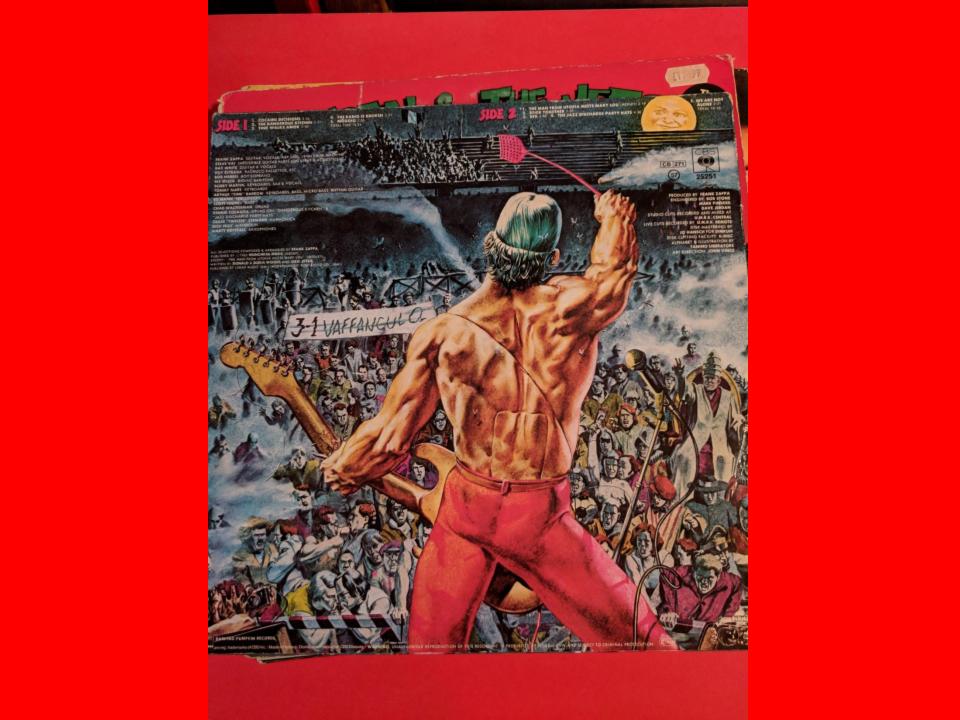

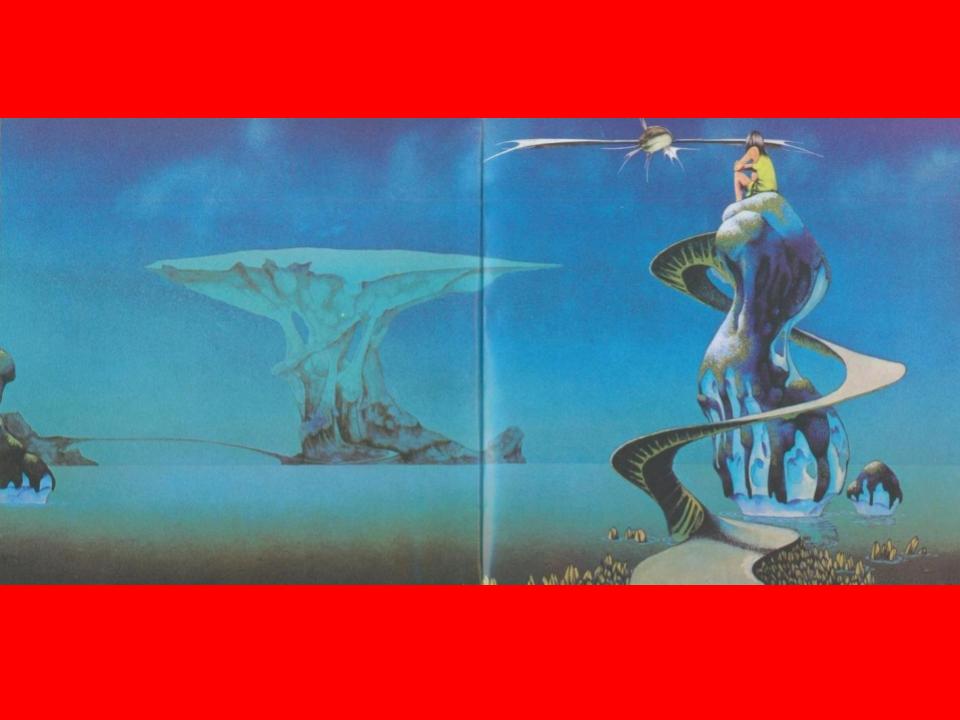

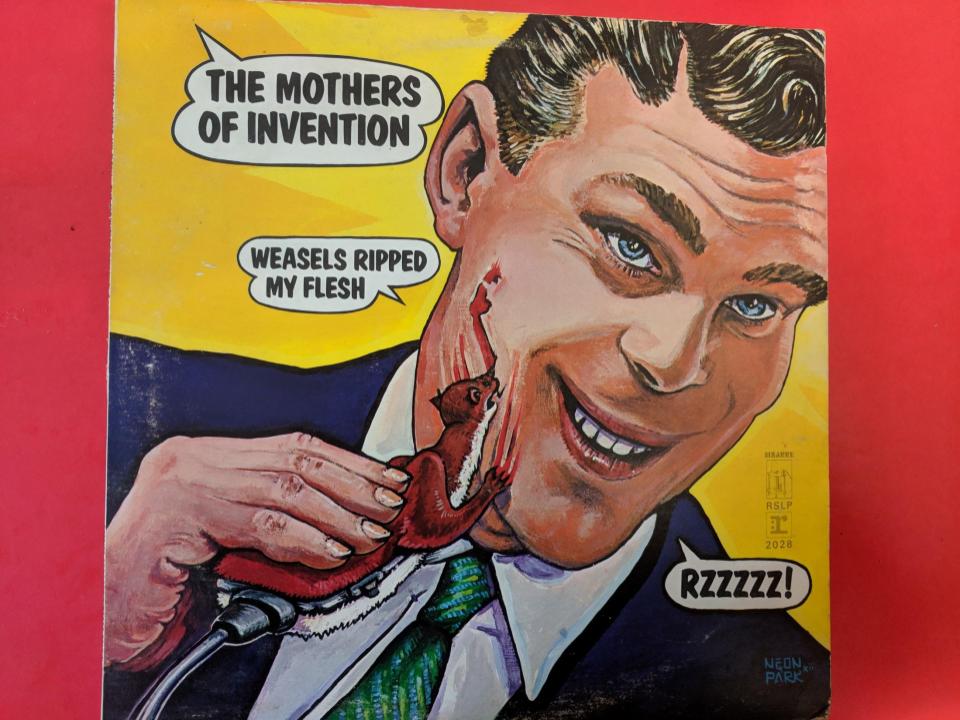

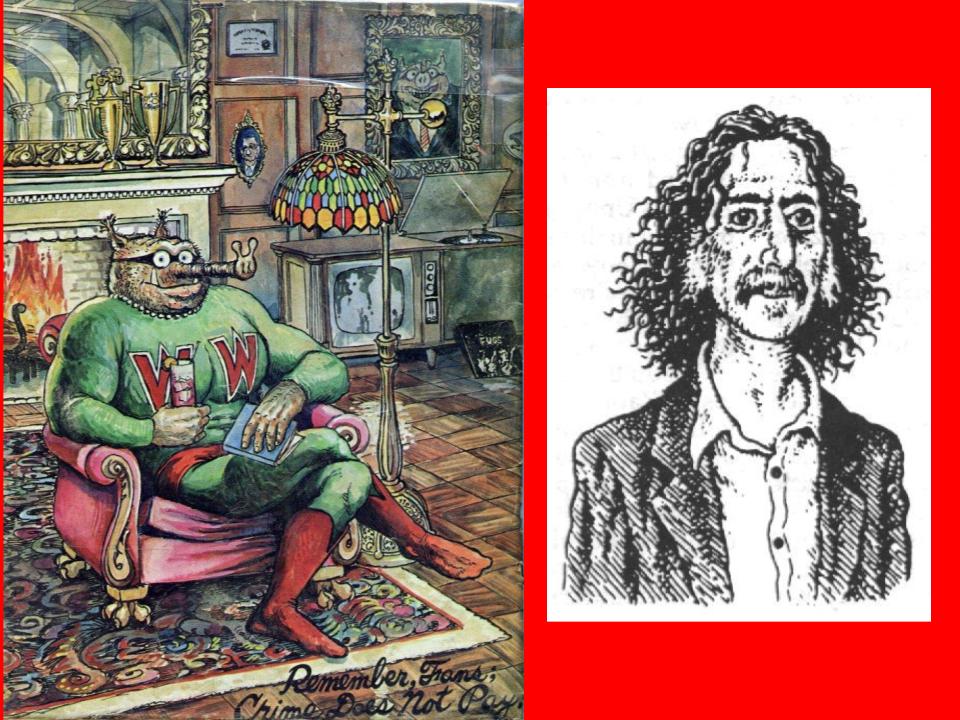

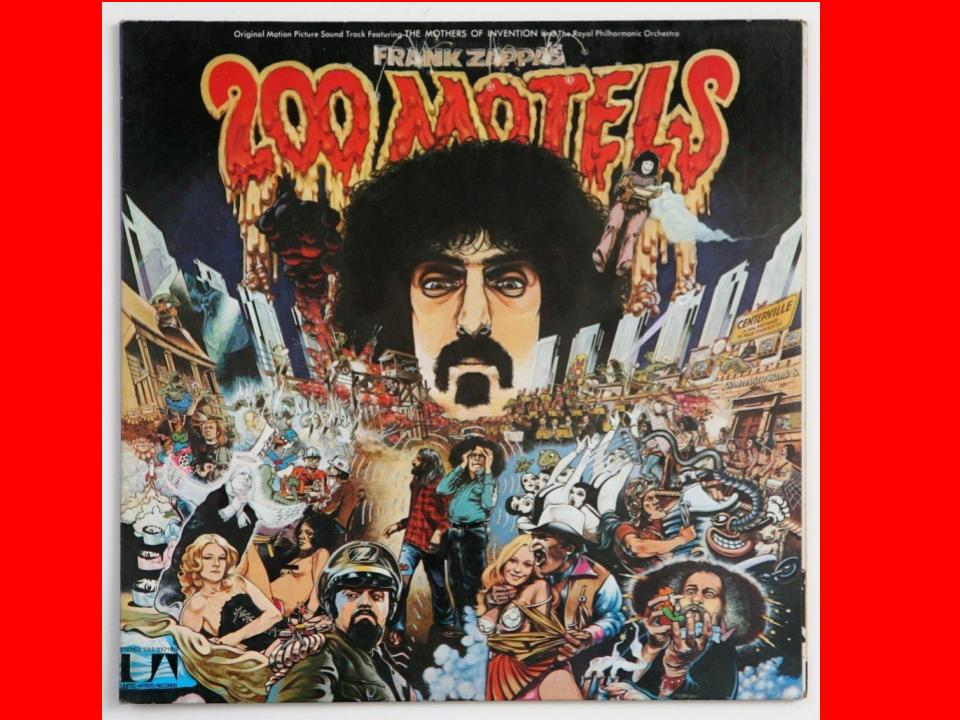

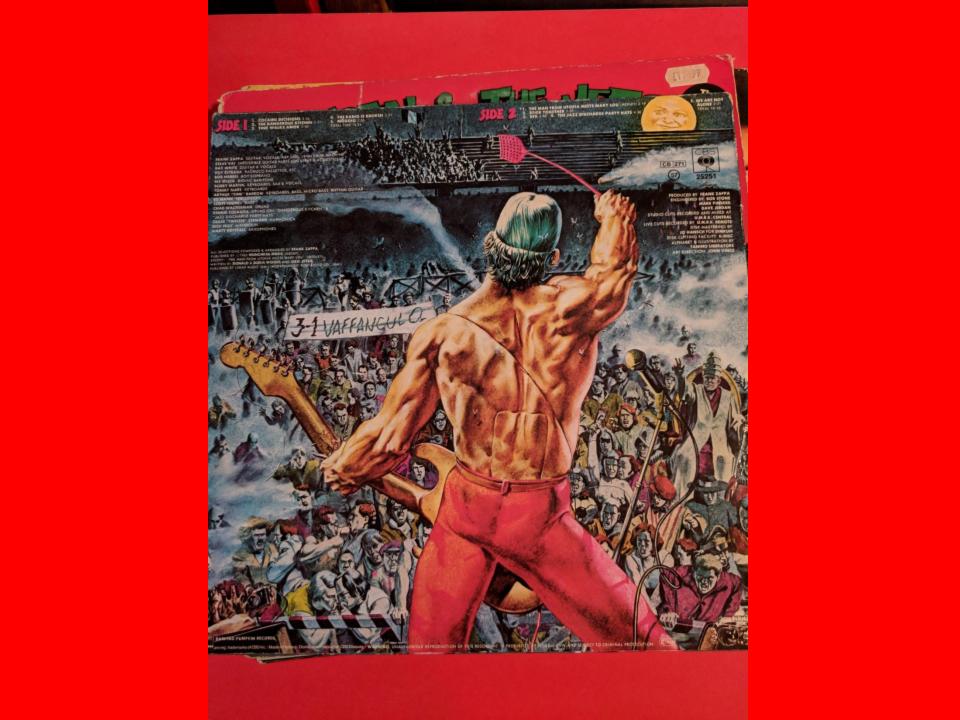

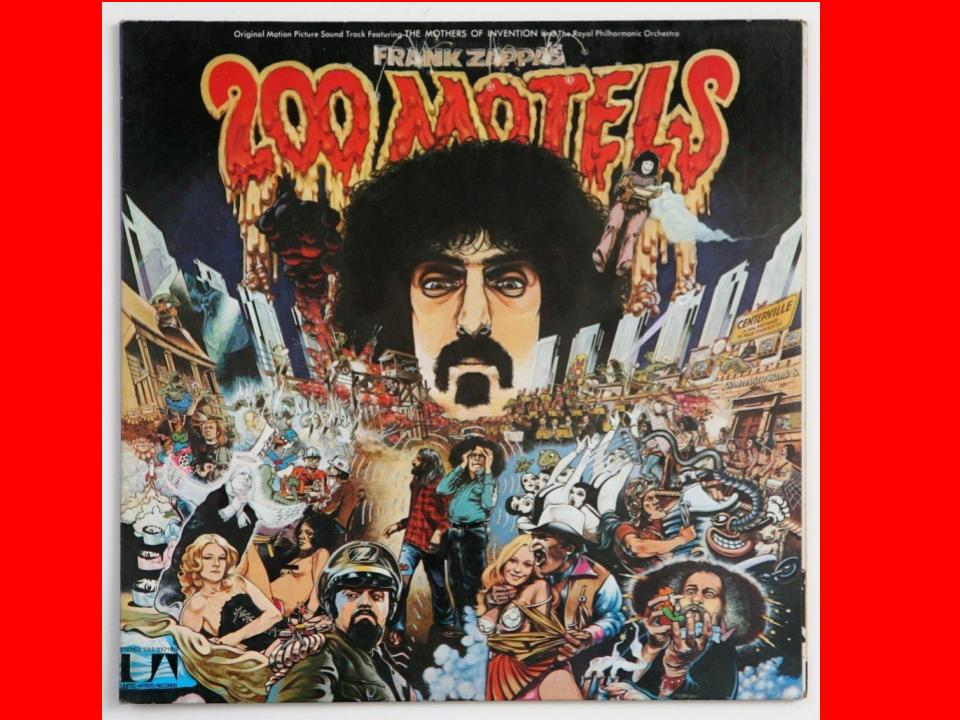

There is much that is comic and cartoonlike about Zappa. Road managers enact gorilla grotesquery on stage. The chaos and send-ups of the low and popular arts is always just a chorus away, as is pricking the pretensions of cultures of distinction. Travesties and cartoonish gags are liberally sprinkled in the song lyrics. Zappa even invented a character – Greggery Peccary – a cartoon character in a cartoon soundtrack, where only the visuals are lacking. And comic strip art can often be found on the album covers. There is a lot of drawing and painting on Zappa’s album covers - unusually perhaps for the rock tradition. Comic-book derived drawings on the album covers were produced by a number of cover illustrators, such as Cal Schenkel, John Williams, Tanino Liberatore and Neon Park. This is not the castles-in-the-sky fantasy drawing of a Roger Dean on Yes albums. Caricature, something biting, sarcastic, is its mainstay. Caricature takes an essential truth about a figure, an event, an object, and manipulates it to squeeze more social truth from it, while diverging from or distorting original surface appearance. Cartoons and comics are deployed for contemplative effect - their deviations from the naturalistic surface of the real are the gaps that make critical or stoned reflection possible.

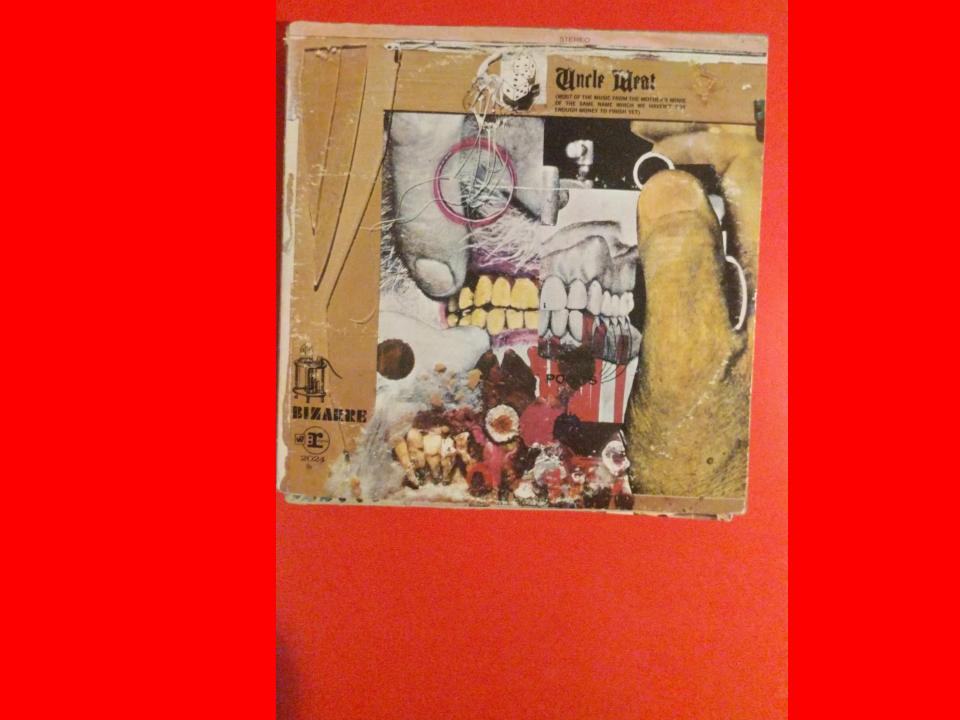

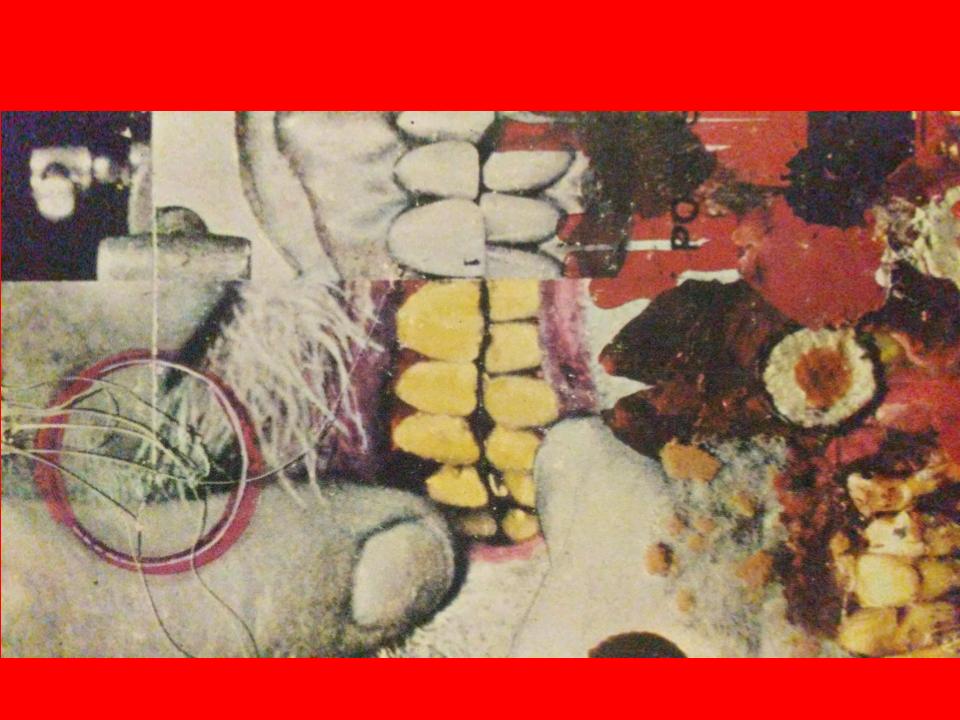

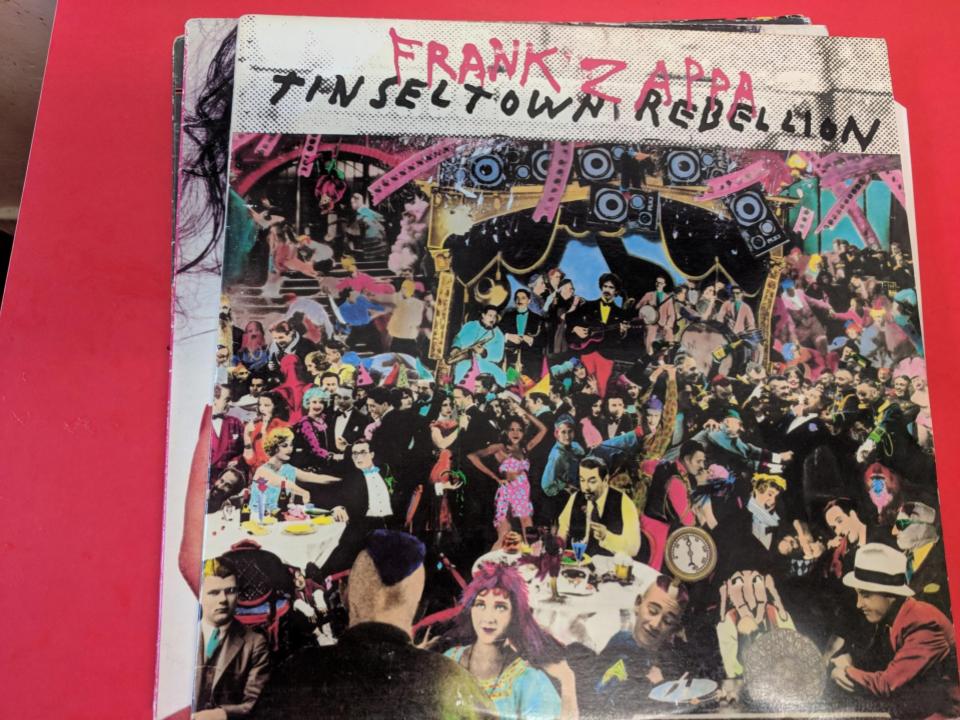

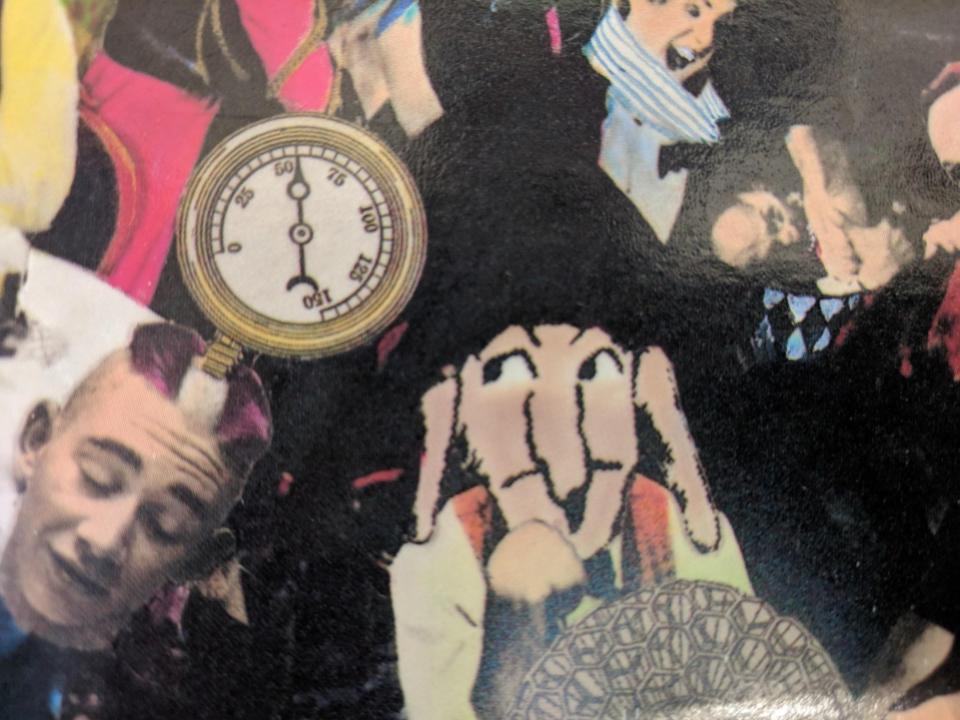

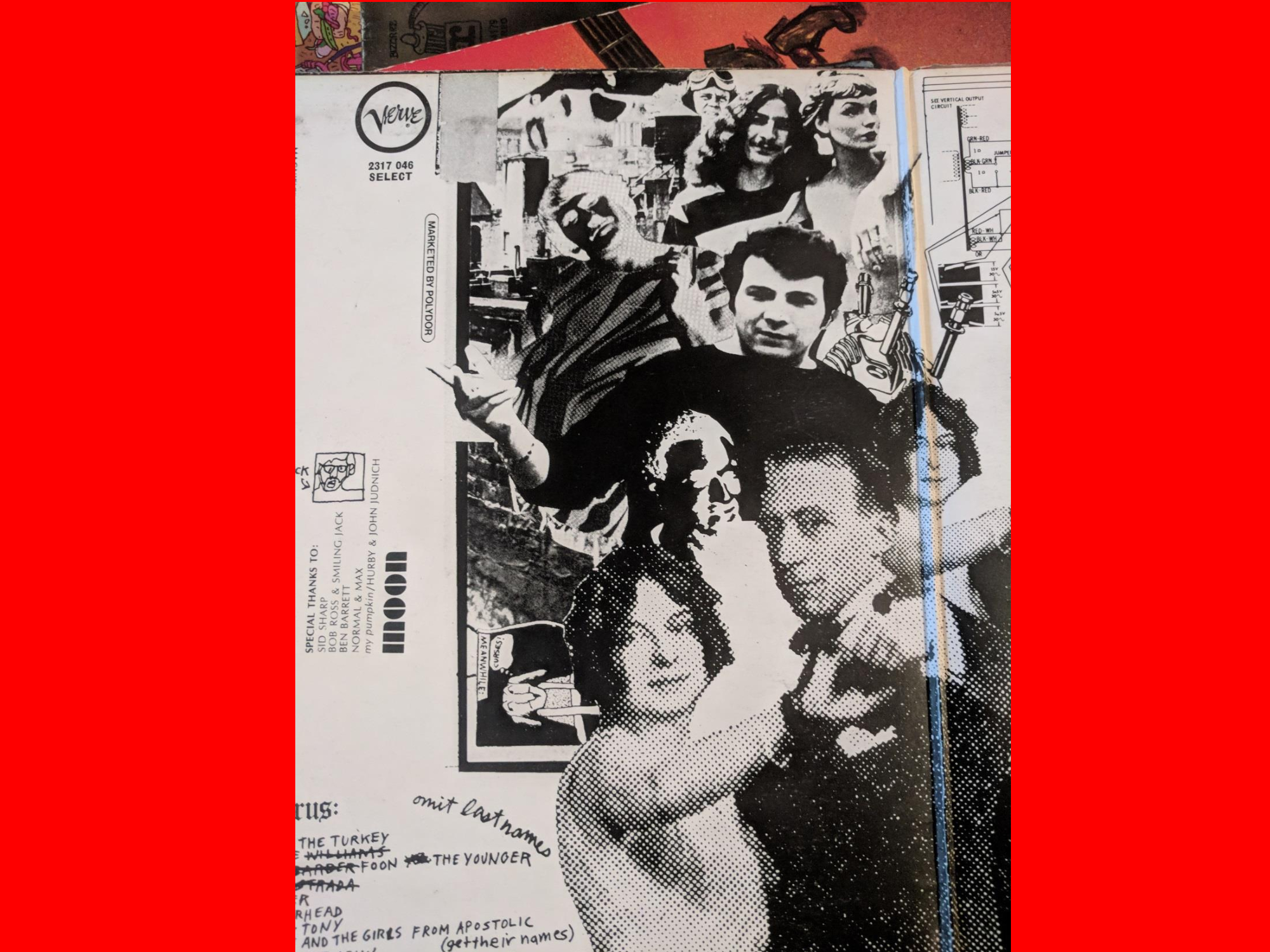

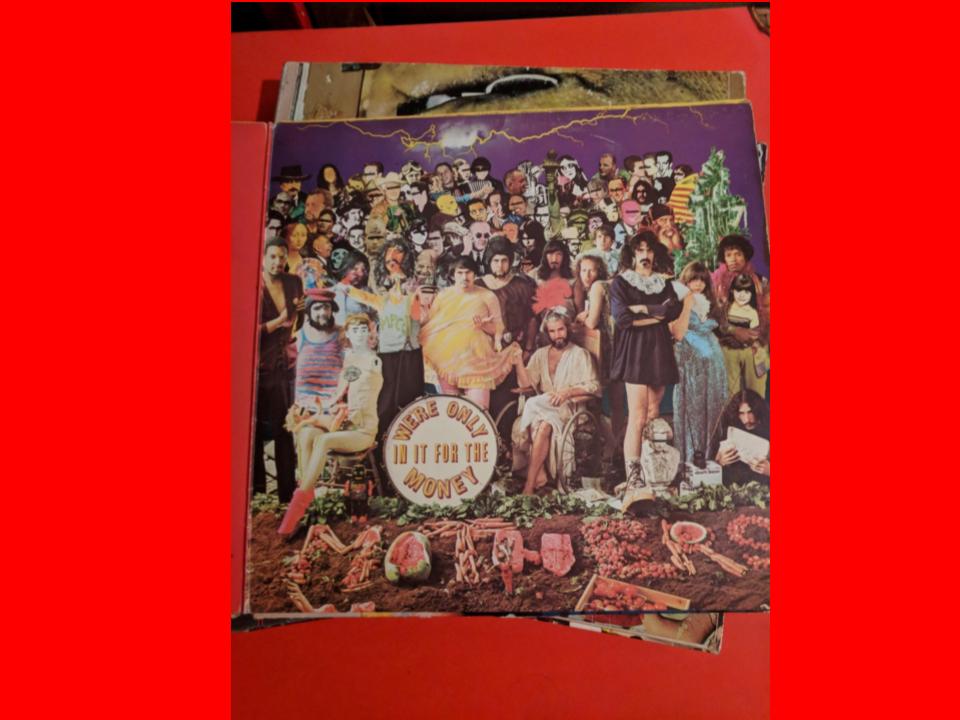

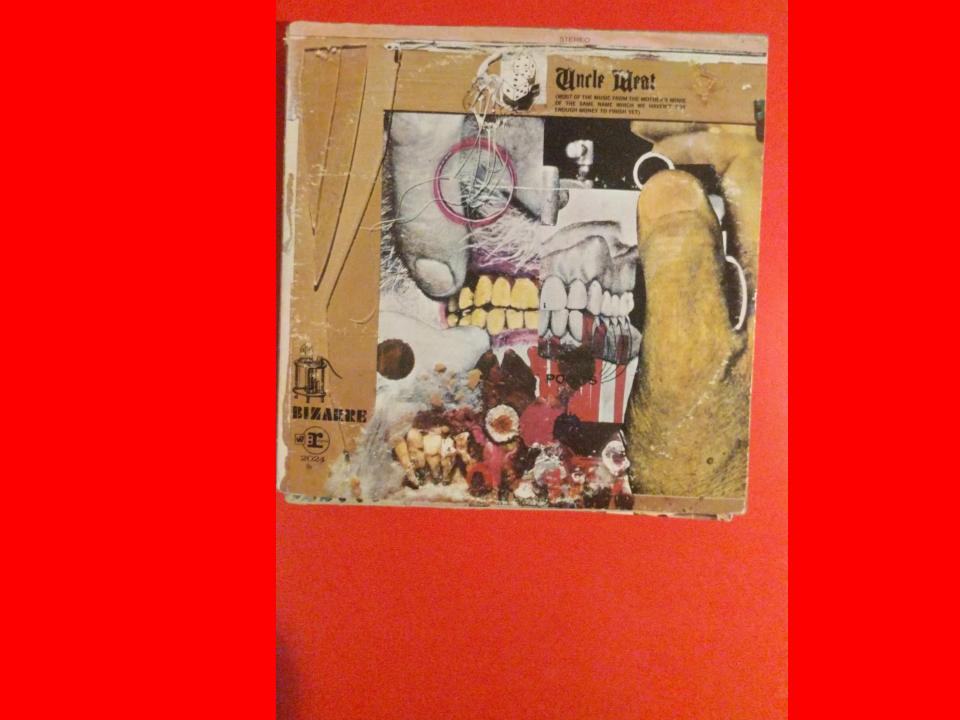

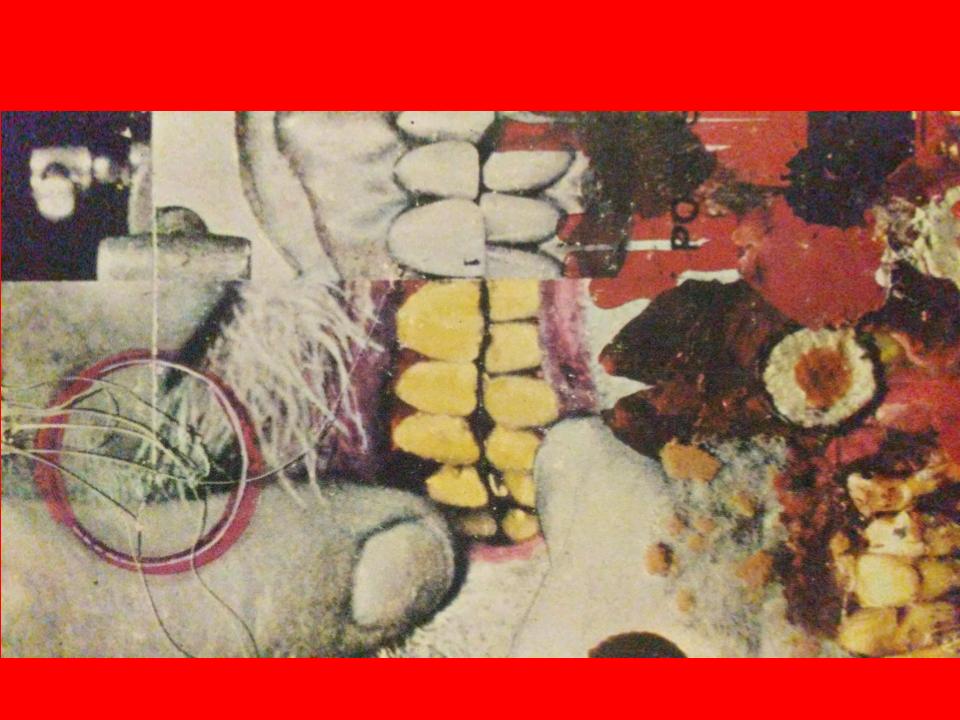

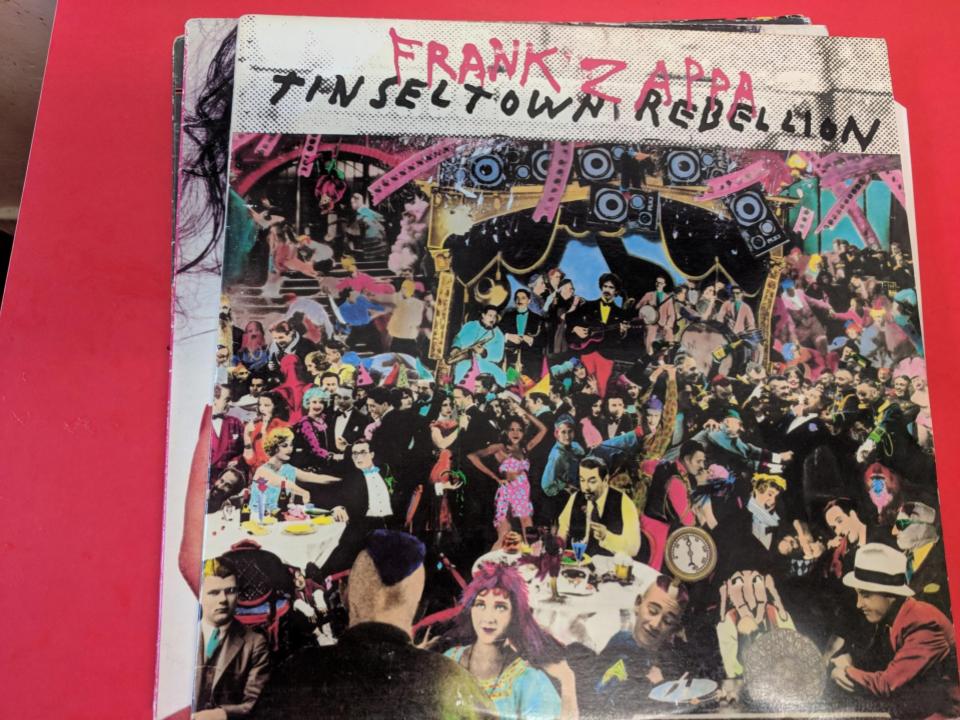

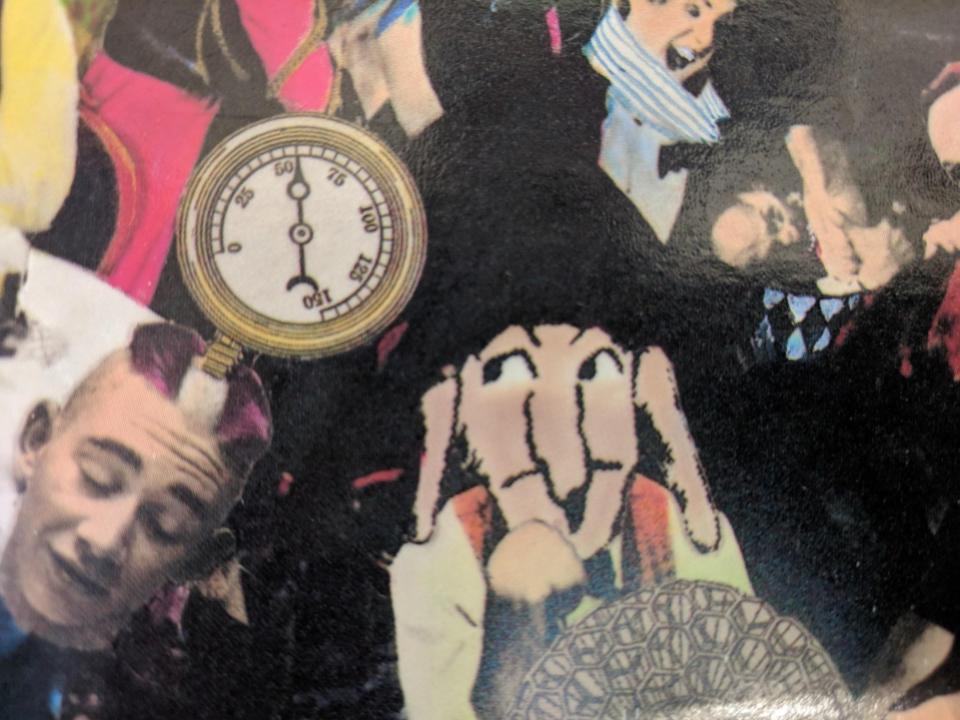

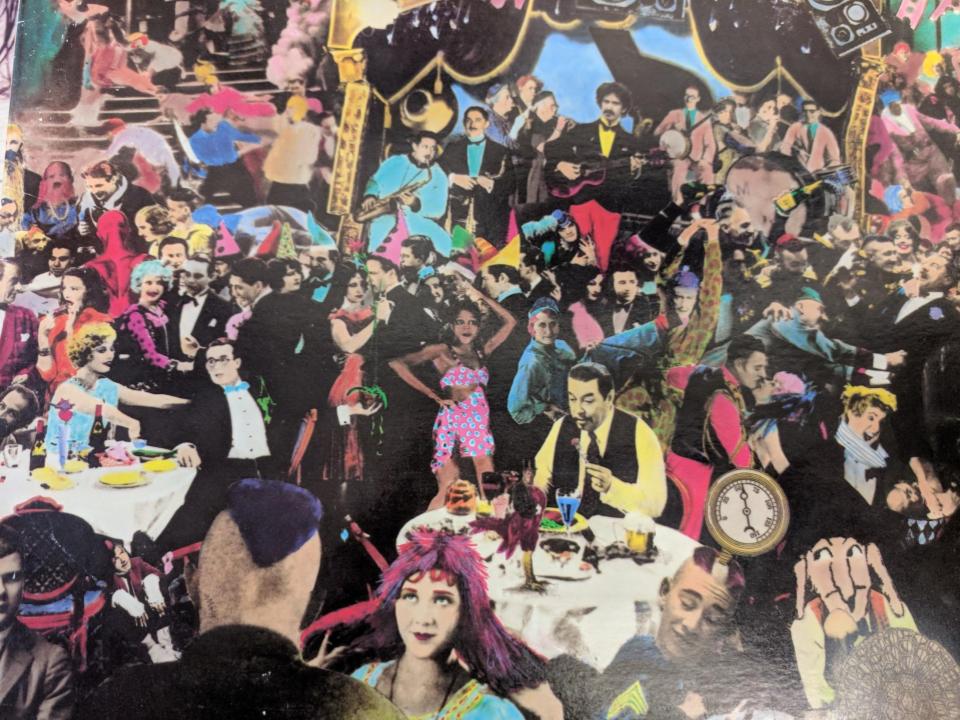

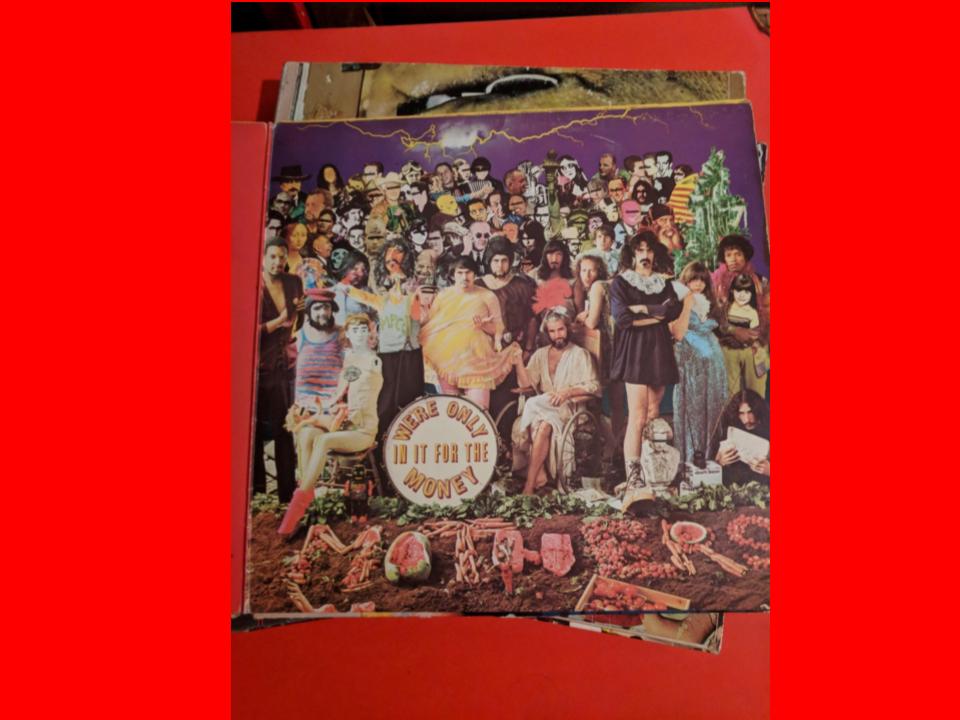

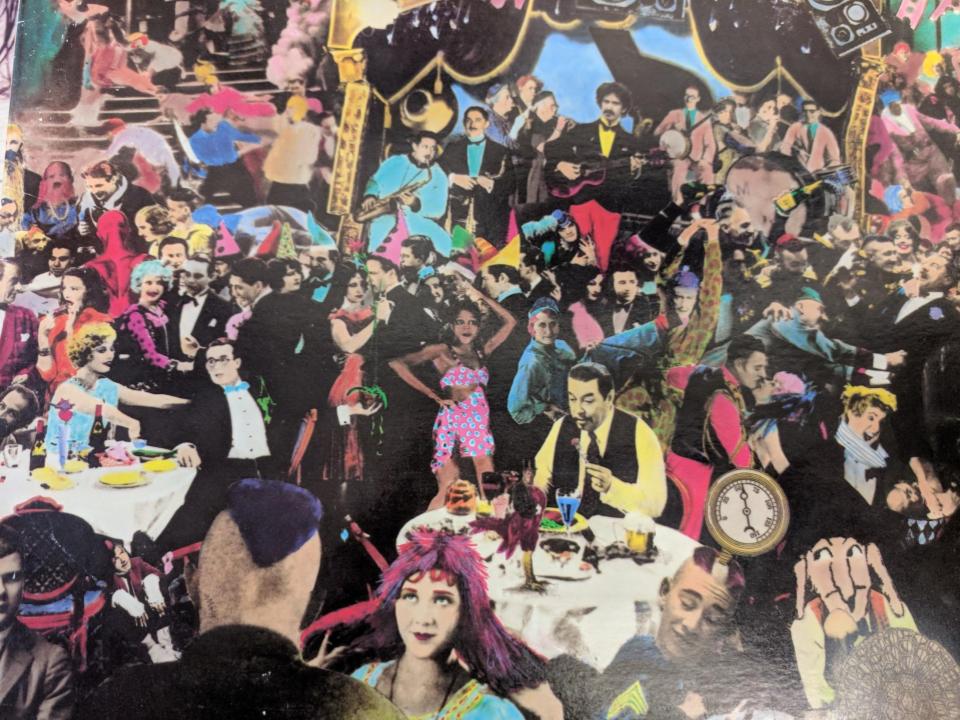

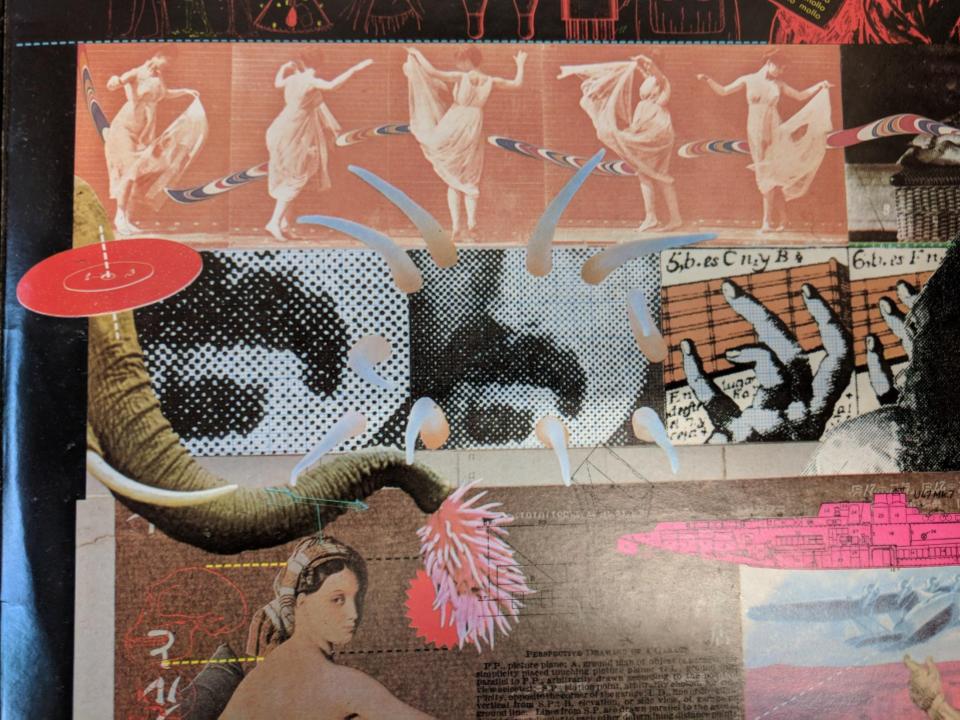

Also frequently appearing on Zappa’s covers are photomontages or collages, which are intrinsically forms that deform the apparent self-evidence of things. Cal Schenkel’s first cover, a parody of the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper, titled We’re Only In It For The Money, from 1967, was a combination of live photo shoot, plaster models and collage. Cruising with Ruben & the Jets laid car parts over people’s heads. Uncle Meat from 1969 collaged teeth, hairs and dental paraphernalia found in Schenkel’s studio, which used to be a dentist’s. Burnt Weeney Sandwich from 1970 was an assemblage of metal and fake flesh. Tinsel Town Rebellion, from 1981, was a collage made of cut up old film stills with densely entwined, colourised bodies like in a Jack Smith movie – it also included a dogface plonked over the head of actress Bebe Daniels in a shot from the 1920 film The Dancin' Fool.

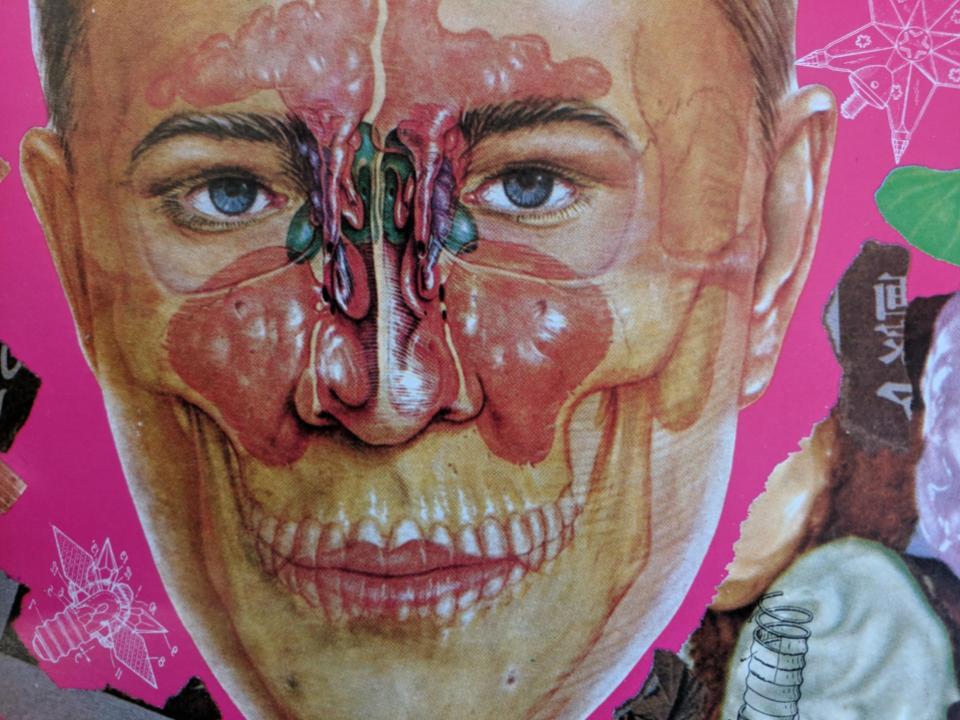

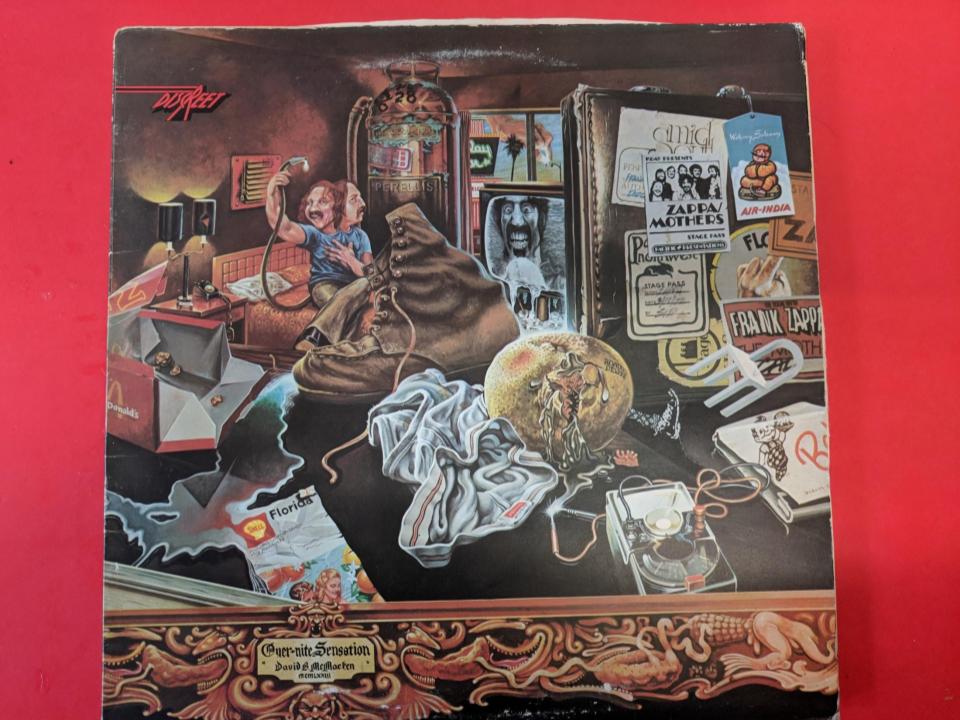

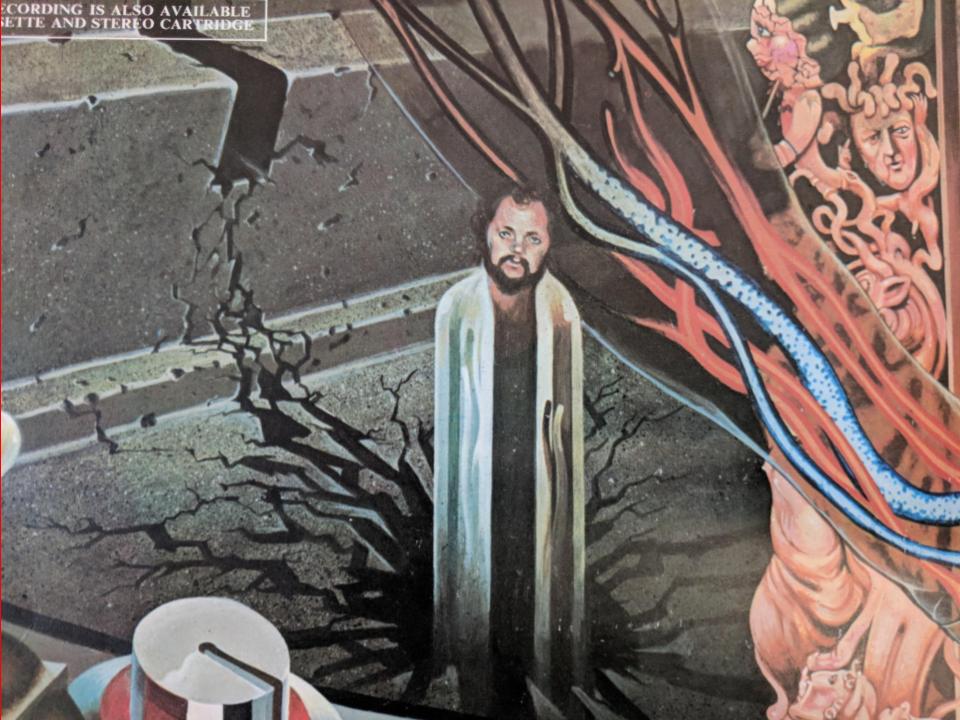

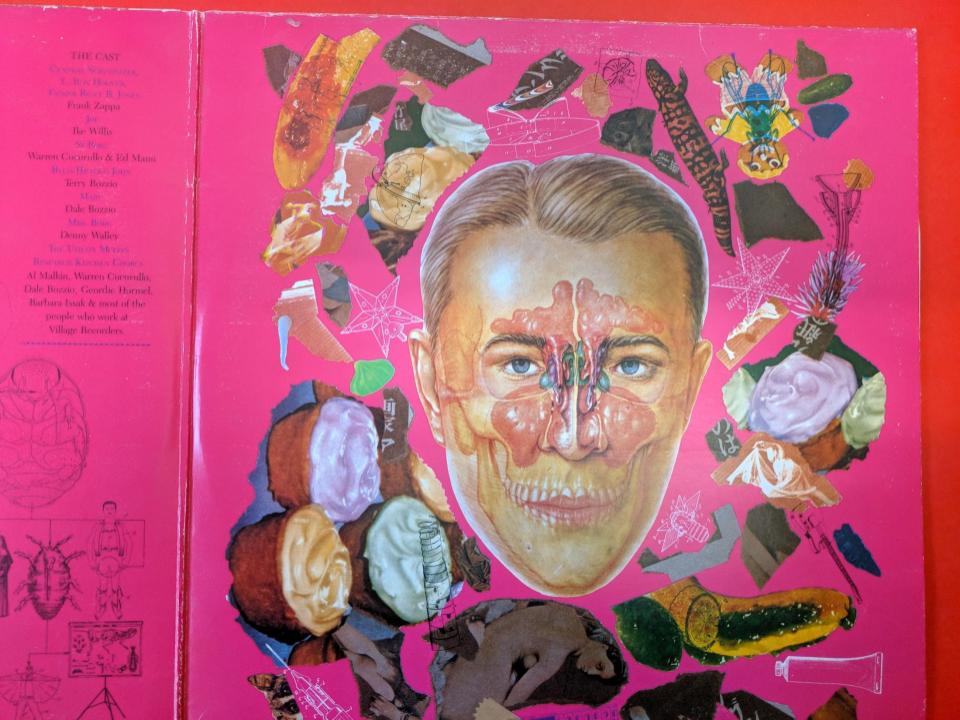

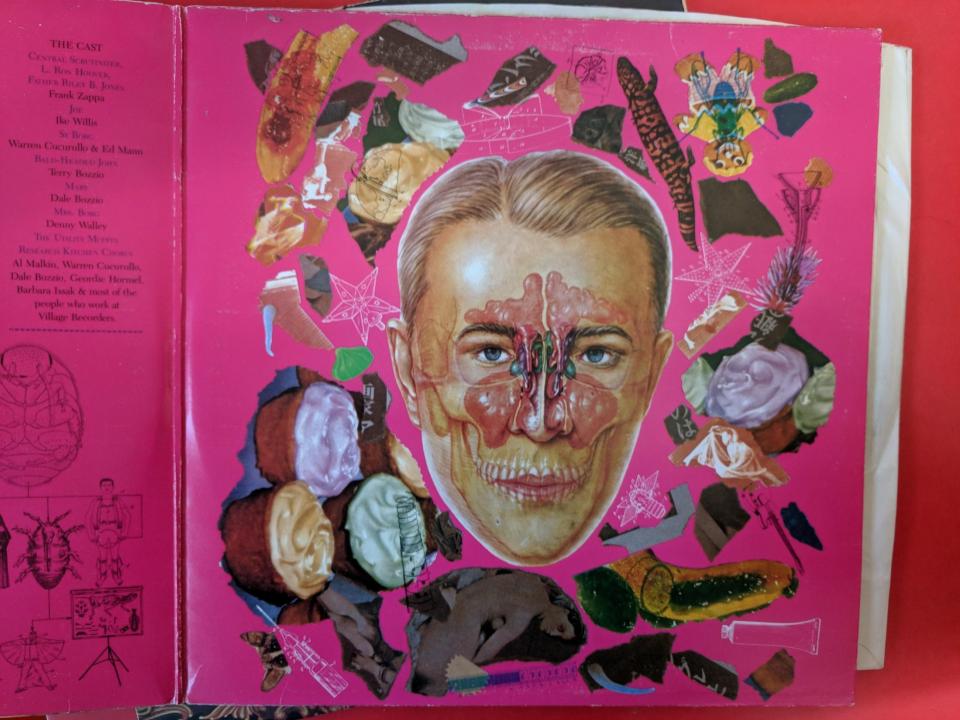

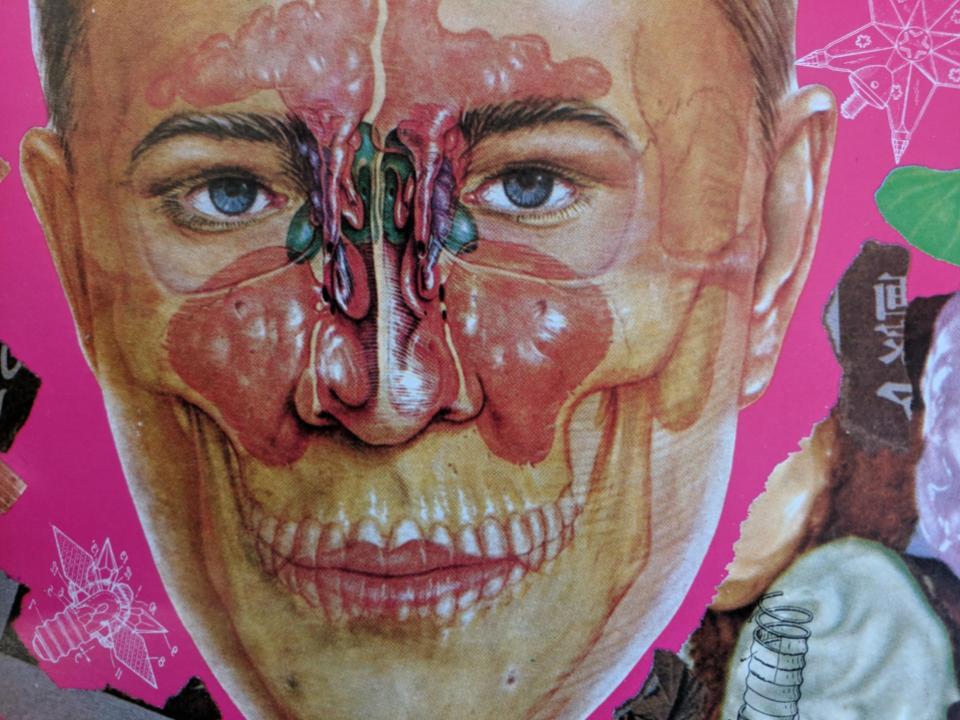

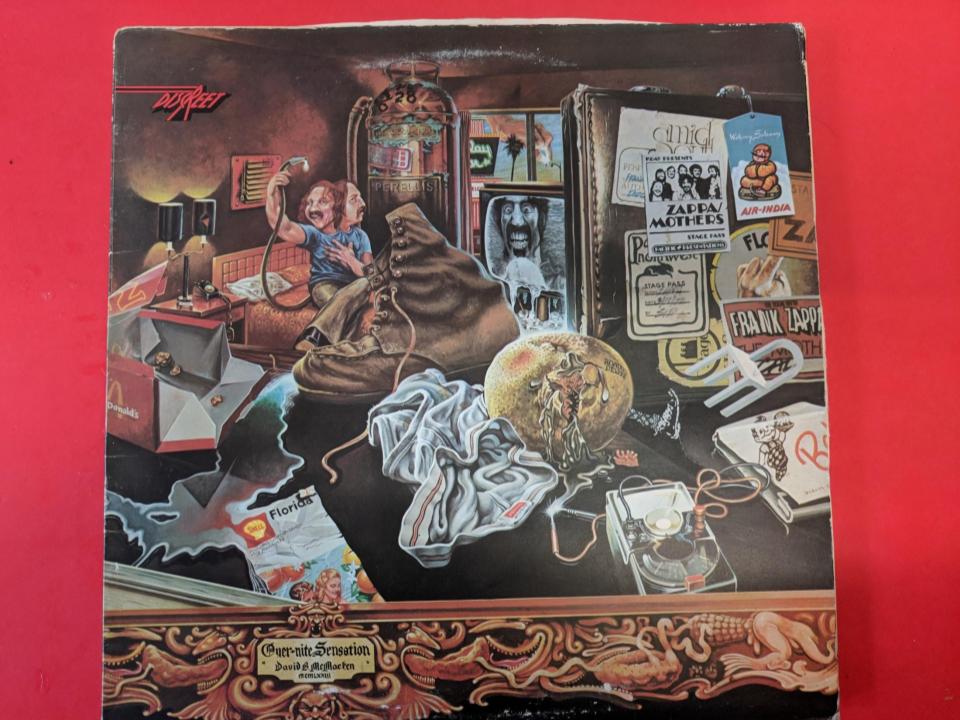

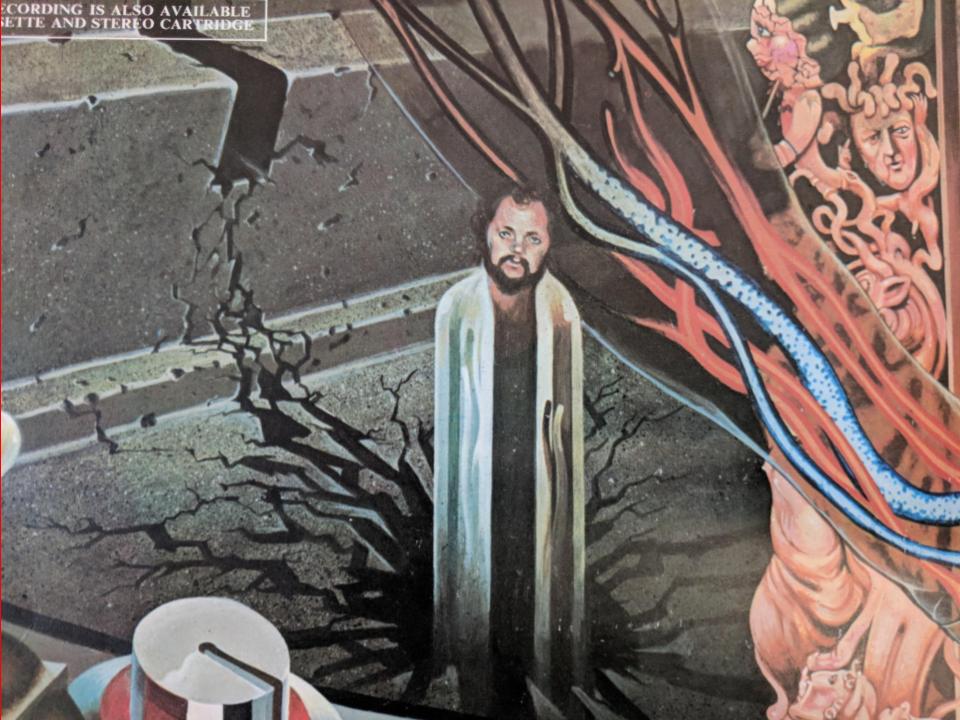

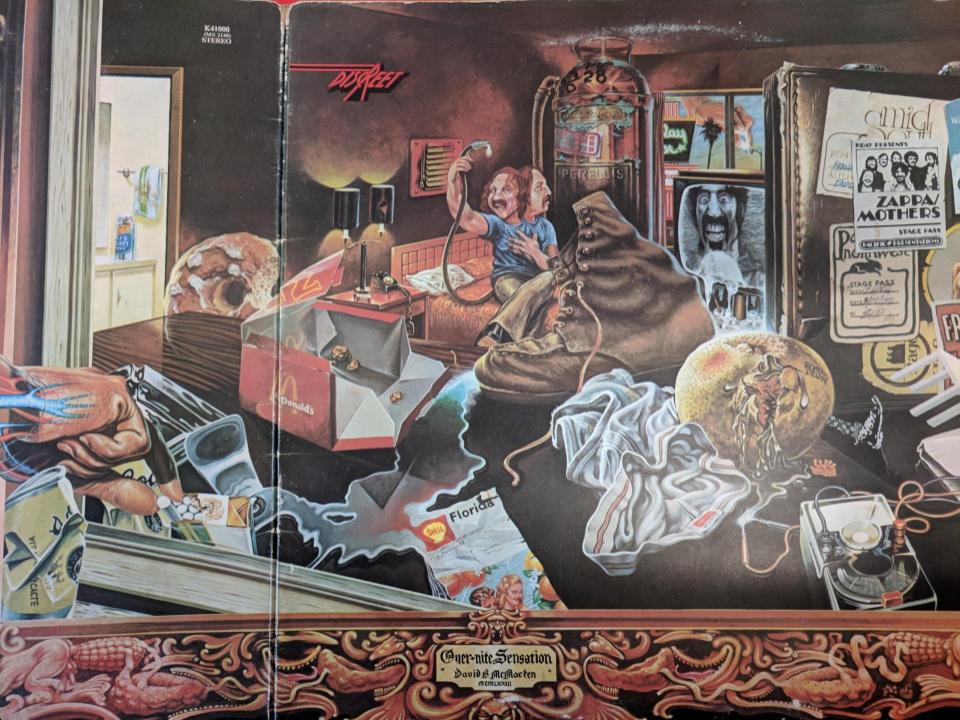

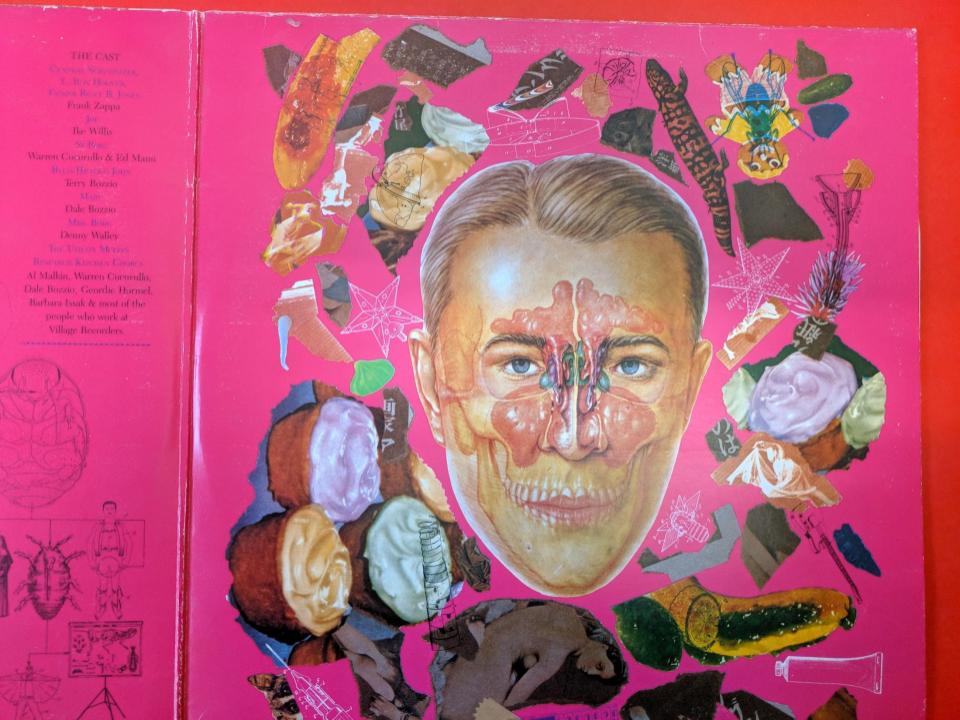

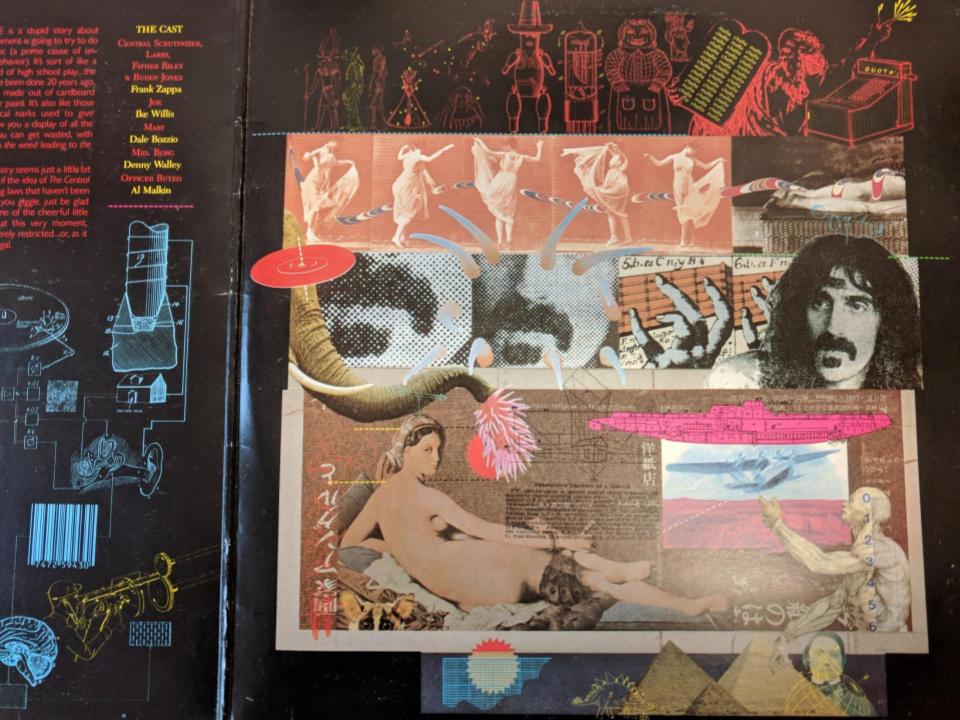

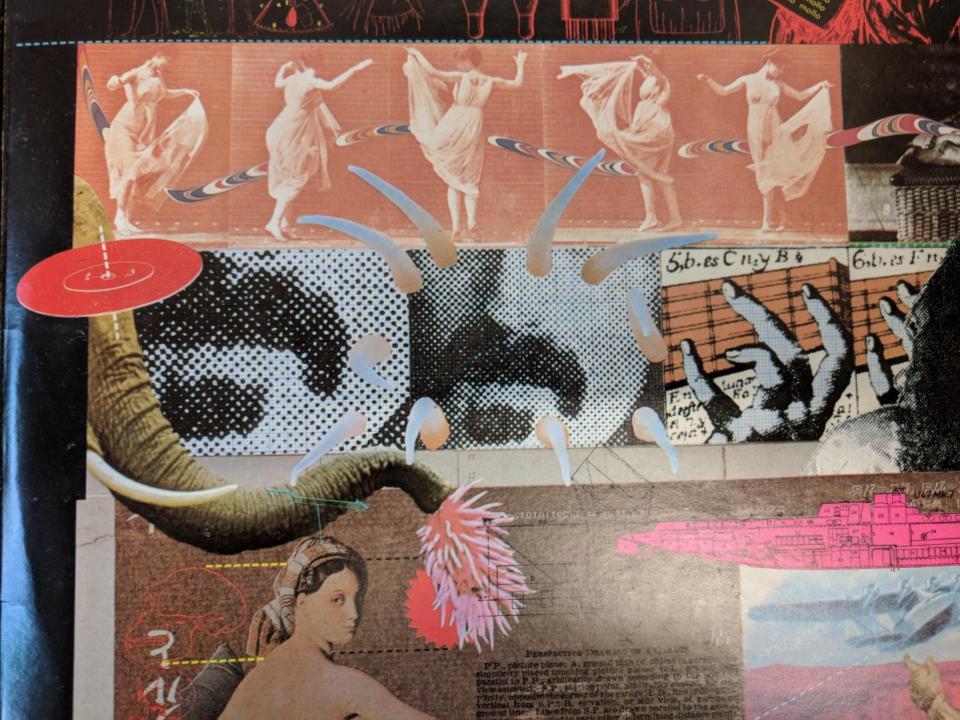

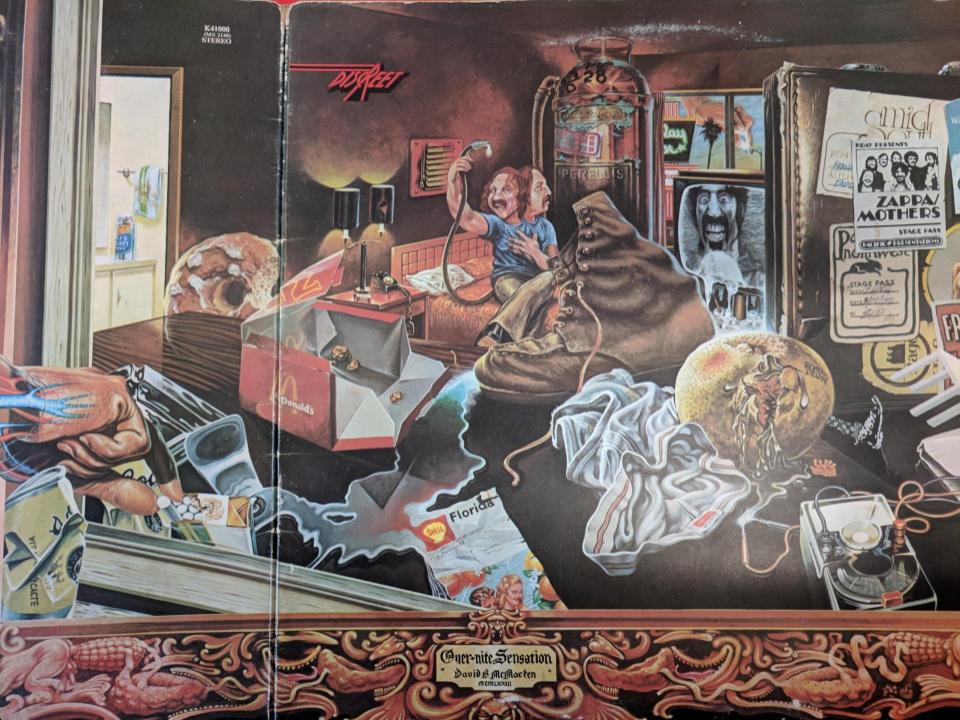

Photomontage and collage are arts of association, producing suggestive links across the surface of an image. Such a principle is, of course, one more widely at work in Zappa’s oeuvre, and known as conceptual continuity. Photomontage and collage crack things apart and then draw them together in a different order, according to new or non-logic. For example, the liner notes of the second volume of Joe’s Garage, by John Williams in 1987, shows a man’s head as it appears to the world and it simultaneously shows the physical aspects beneath the surface, the teeth under the lips, the bloody innards behind the nose. There is the outline of a skull. Bone and blood push to the fore. What is within is revealed, made obvious. Depth is revealed behind the surface. The face is altered through aesthetic procedures in order to make manifest to viewers something about the materiality of the self. It makes visible the invisible workings of the body, the sinuses and nasal passages, in particular, that is, the substructure, which is what is essentially mammalian, the routes through which pass air to breathe and from which waste is ejected and unwanted invaders barred. The collage deals with the processes of life itself, the life beneath the mask of civilization – for those intimate with Zappa’s early biography the relevance of sinuses and their correct functioning will be clear: a sufferer of sinusitis as a child, and treated by radium pellets shoved up the nose. One of Zappa’s favourite childhood toys was, after all, a gasmask, with its filter removed and its plastic tube supplying the wearer with the ‘unfiltered air of the environment’. Such exposure prefigures Zappa’s interest in sucking in the raw data of our world, a practice of excessive and seemingly indiscriminate digesting and recombining of all the contents of the universe, which is also what manifests itself in the messy chaos of the album covers, as in, for example, 1973’s Over-Nite Sensation, with its painting by Dave MacMacken, depicting numerous details from the tour bus, underpants, sexually abused grapefruit, the foot of the sound mixer of the Beach Boys, Herb Cohen disguised as a radio tube, an artwork from a Holiday Inn bolted to the wall, amongst other salient details.

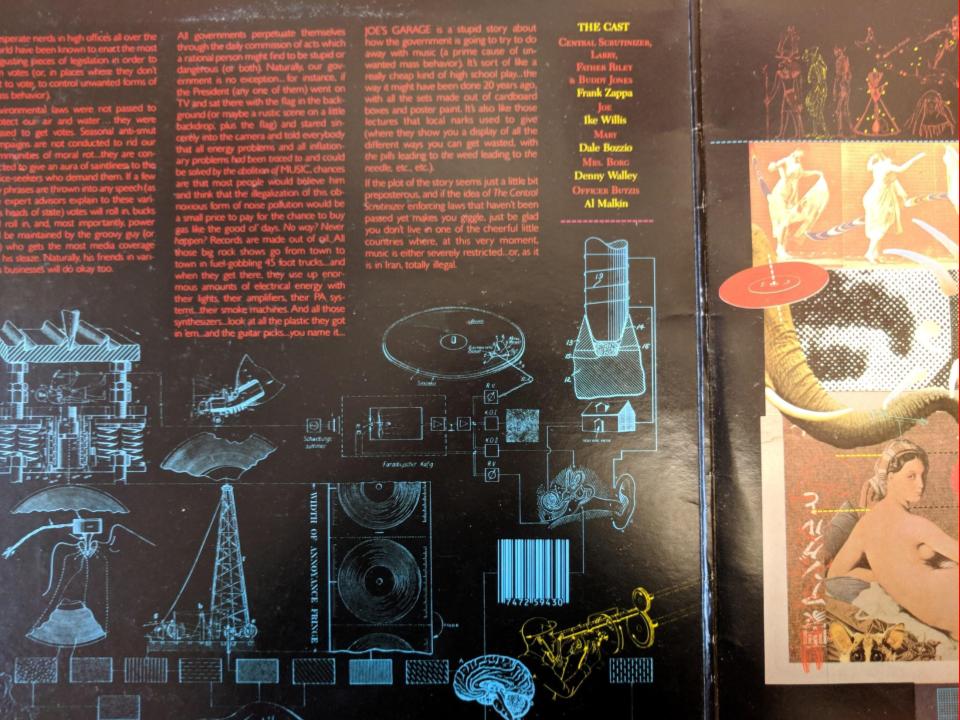

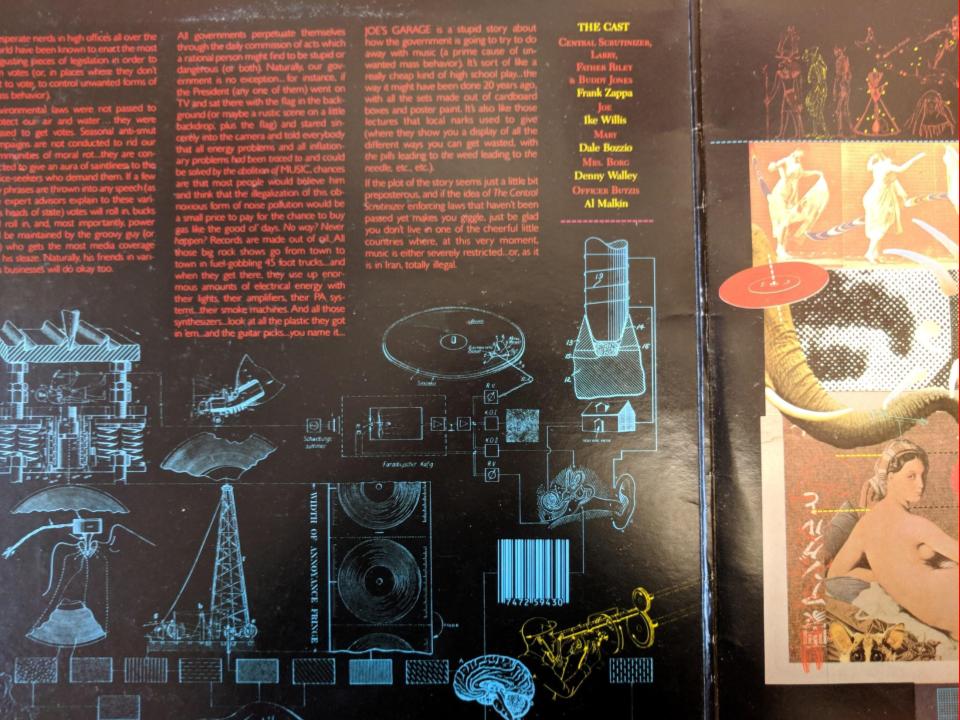

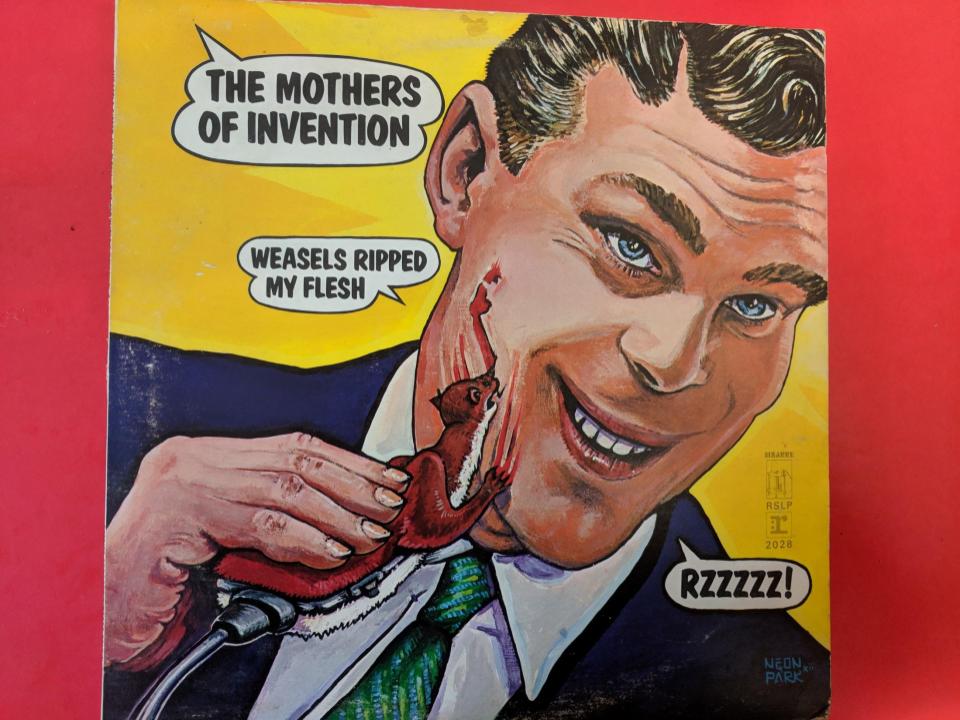

The image on the inside cover of Joe’s Garage compares to that on Weasels Ripped My Flesh from 1970 by Neon Park – again a straight-looking head taken apparently from a 1950s men’s pulp magazine, slick-looking, clean-cut, is under assault by an electric razor that is a weasel. A surface is disrupted to show what is underneath. The coherence of the flesh’s surface is torn, the blood beneath seeping out. It appears as an analogy for the violence that underpins civilization, as interpreted along the lines of Adorno and Horkheimer’s claim in Dialectic of Enlightenment, that the nature abused in the process of civilization will turn on that perfidious part of nature called man, until eventually, the whole elaborate machinery of modern industrial society is nature bent on ripping itself to pieces. The image inside Joe’s Garage, volume 2, does not portray nature’s self-annihilation. Rather it shows life processes, depicting how human life is sustained by its ‘backers’, the items strewn around the head: muffins, a banana, sex or perhaps a mother figure. There are hints here of our lower selves, insects, reptiles and some references to human cultural aspiration in the form of a tube of paint and some curious diagrams. The lyrics of Joe’s Garage imagine a world in which all this self-activity, low and dirty as much of it might be, is repressed, and music is banned, because it is ‘a prime cause of unwanted mass behavior’, with a ‘Central Scrutinizer’, a totalitarian busybody suspending democracy and ‘enforcing laws that haven’t been passed yet’. Joe’s Garage thematises the ersatz products of this nightmare society: canned music, disco-dumbness and MTV videos, ersatz philosophy in the form of a religious cult and ersatz mechanical and inter-species sex.

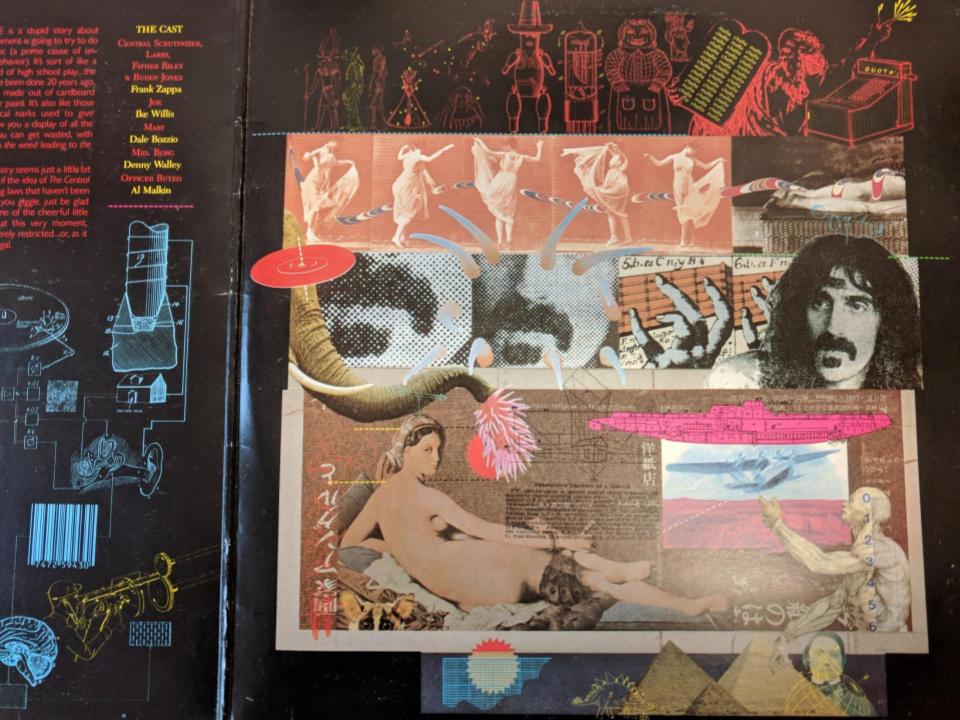

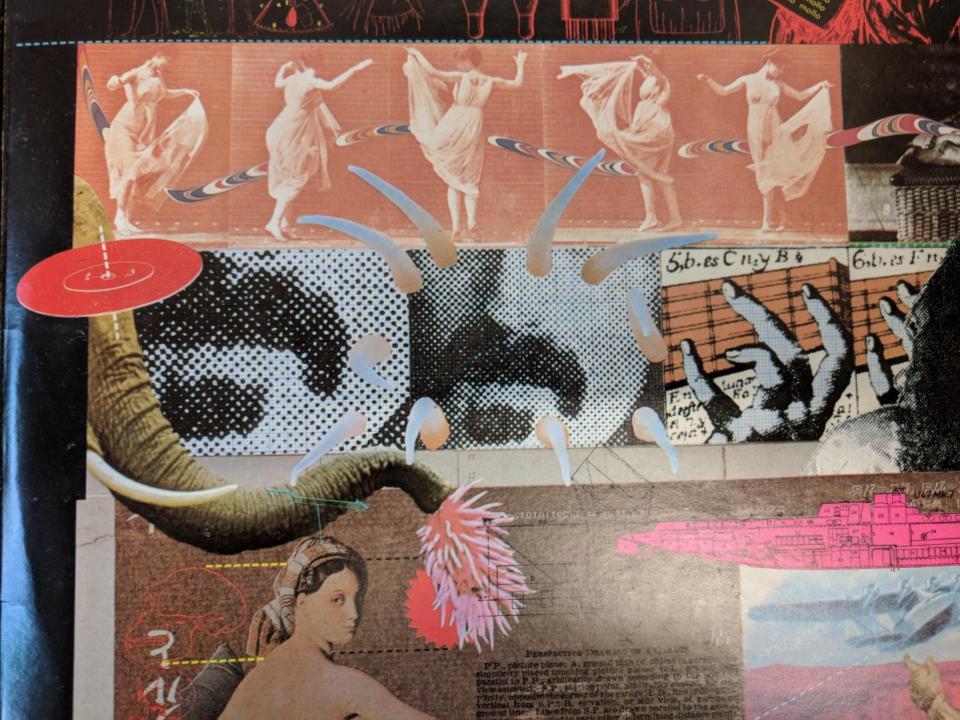

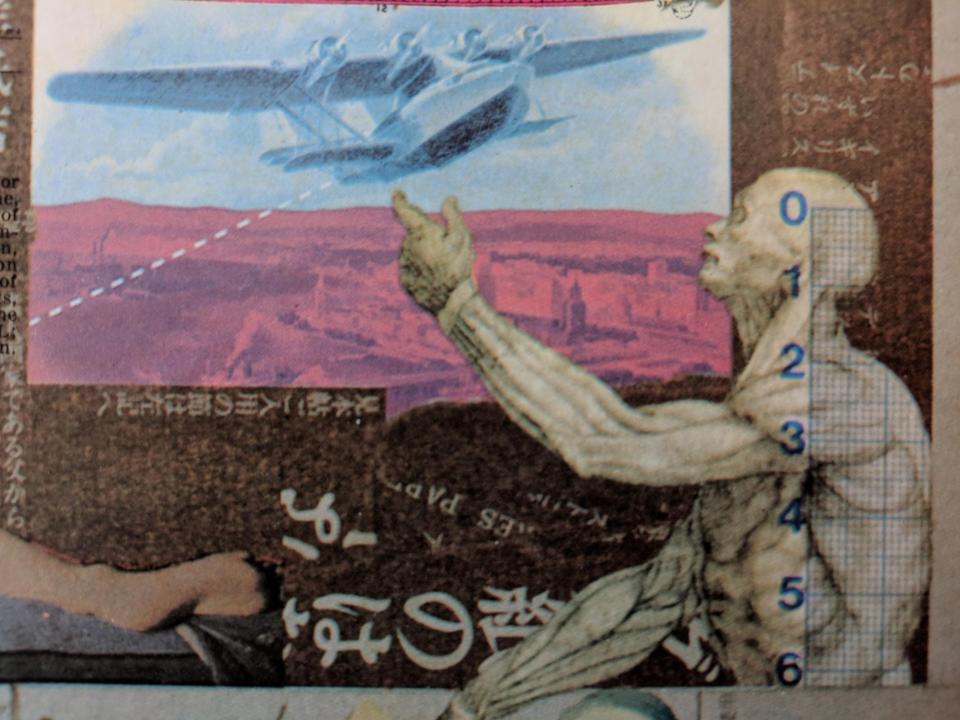

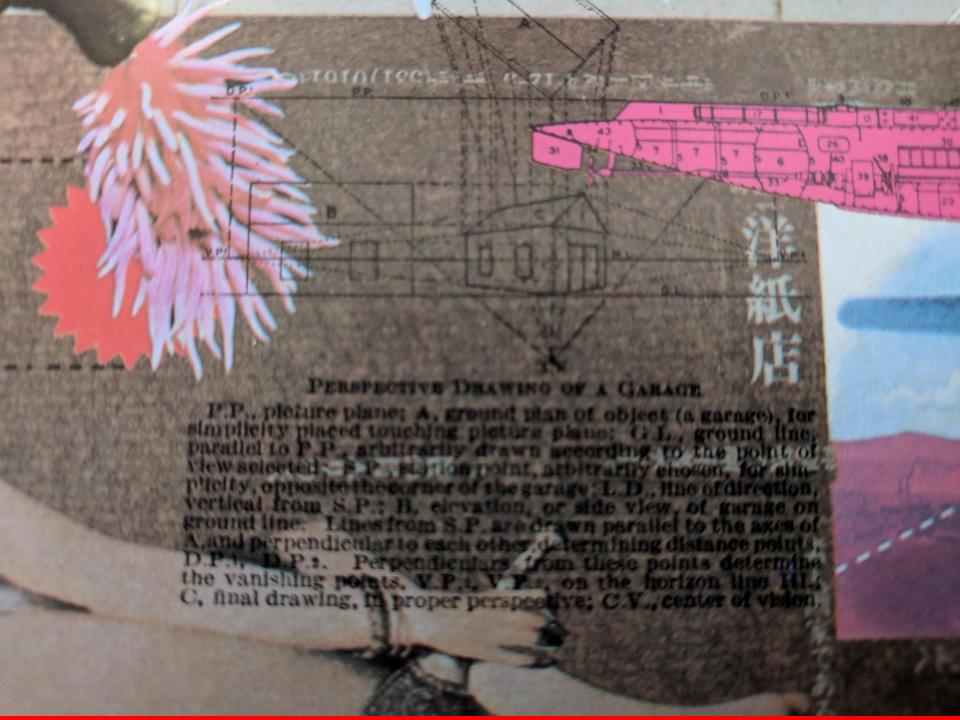

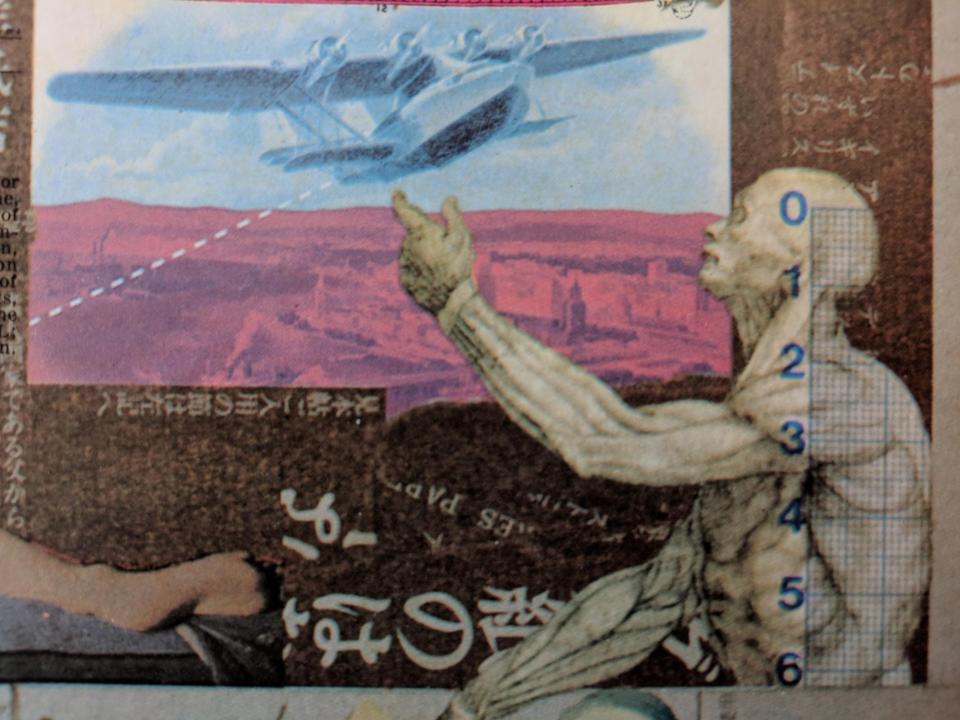

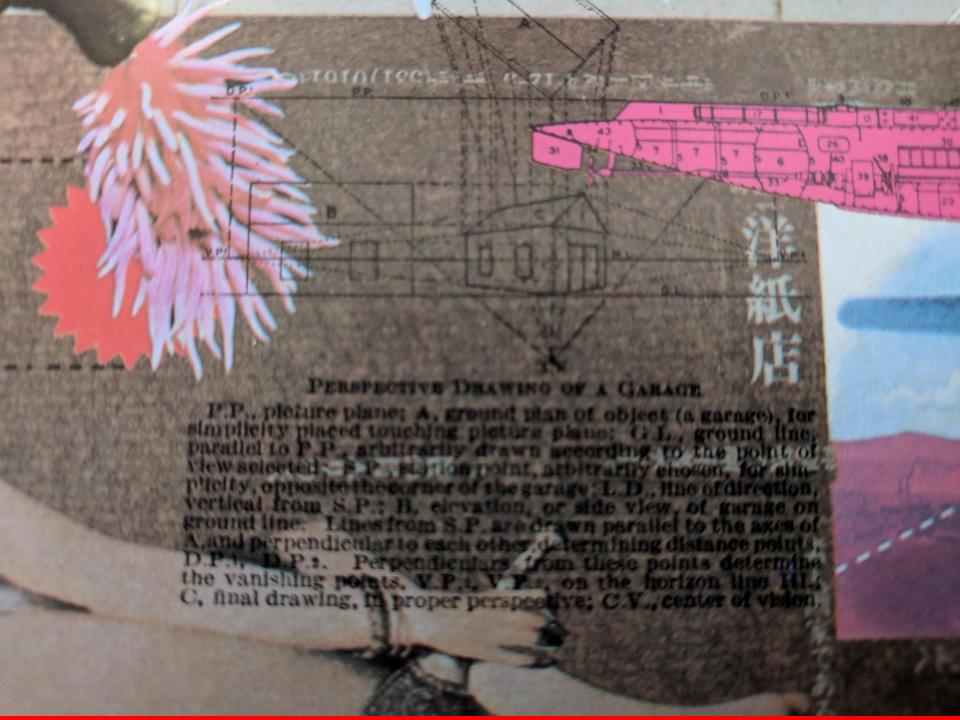

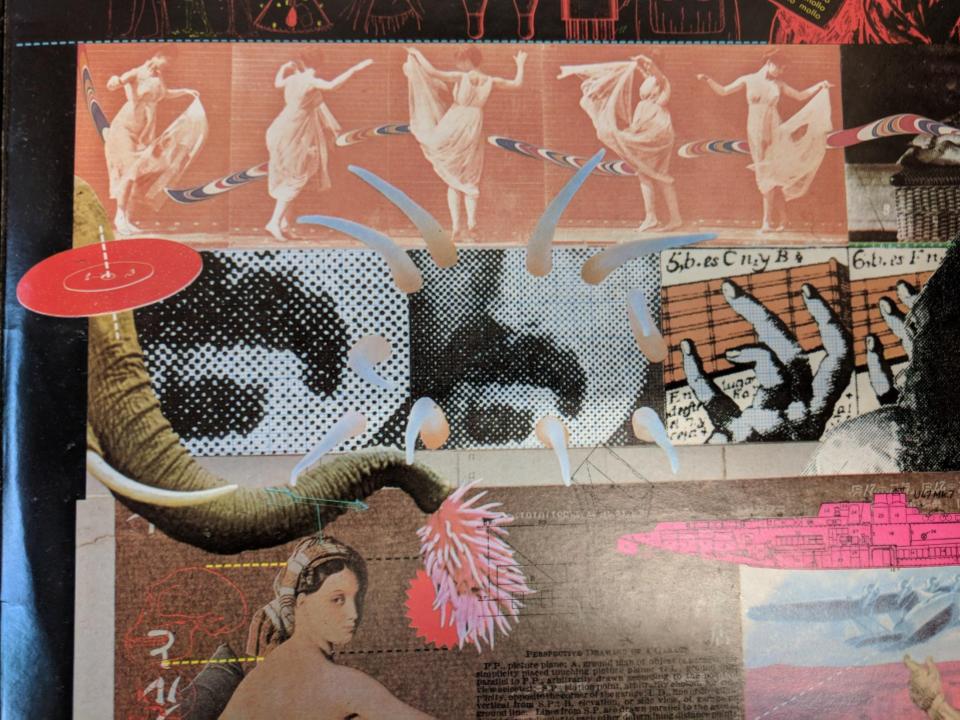

The liner notes to the first volume of Joe’s Garage presents a bewildering photo-collage. It combines images of a female body, a flayed male body, a male head (which is Zappa’s) and instructional or analytical diagrams. Here we see the theme of surface – bodily surface, including close-ups of that body surface, accompanied by the themes of drawing and labelling – that is to say, items are presented as mediated through the artist’s hand and labelled, in an effort to make them available to knowledge, science or guided interpretation. In fact, it might be said that the flayed body is like one of the diagrams, as it shows what is beneath the surface, in an echo of the skull-head on volume 2. Exposing human musculature was originally meant to provide knowledge of the body for aspiring medical men and artists alike in the Renaissance. Such drawing is a means to discovery, an analytical re-inscribing of things, motivated by similar impulses as photomontage, which was an effort to undermine the apparent truthfulness of photography, as light rays from objects’ surfaces strike silvered paper. Photomontage or collage of this sort does not aim to provide a single perspective view of the world and its contents. Rather it produces dense pools of illuminating light across a variegated field. It is more interested in showing interrelations, in expressing how things mean and mean differently in the context of other things. There is a drawing of a garage on the cover for Joe’s Garage volume 2. It is clipped from a book on perspectival drawing. The drawing and its caption explain how to produce the illusion of perspective in a drawing of a garage. Such illusioning, the basic tools of conventional art since the Renaissance, is not what the rest of the album cover undertakes. In fact the juxtaposition of different drawing styles makes for a critique of representation and a historicizing of its forms. Perspectivalism, while the basis of conventional realism, appears here as the most distant from reality, the most fake. Against its mathematical dissection of space, made into a geometric ideal, the surrounding images exist in a fracturing of space that produces something like a temporal analysis of the spatial: the cover is laid out such that the viewer is encouraged to read it as a series of images such as would appear on a film strip. The cover appears to be composed of a series of frames, some of which run together to produce mini-sequences, a photographic series of a dancing woman, a shifting close up of Zappa’s moustache that cuts to (his) fingers playing a chord on the guitar, and then pans back to reveal his face.

If the filmic referent is not convincing, perhaps it is more persuasive to argue that it, like other Zappa covers, borrows its aesthetic outlines from comic strips. The comic strip, like much popular culture, absorbed and refracted the energies of the dynamic capitalism that spawned it. It is a format that became synonymous with US culture, and it developed in various directions, from tales of scruffy ragamuffins and primitives to superheroes and, in the 1960s, it developed a countercultural, underground branch, without which Freak Culture, such as from Crumb and Gilbert Shelton, was unimaginable and from which Zappa’s cover artworks emerge. While comic strips assaulted the pretensions of high art, the arts of distinction, they also generated, through fan cultures, their own communities of experts, who enjoyed their self-referentialism, reflexivity, their intertextuality, their mind-expanding conundrums.

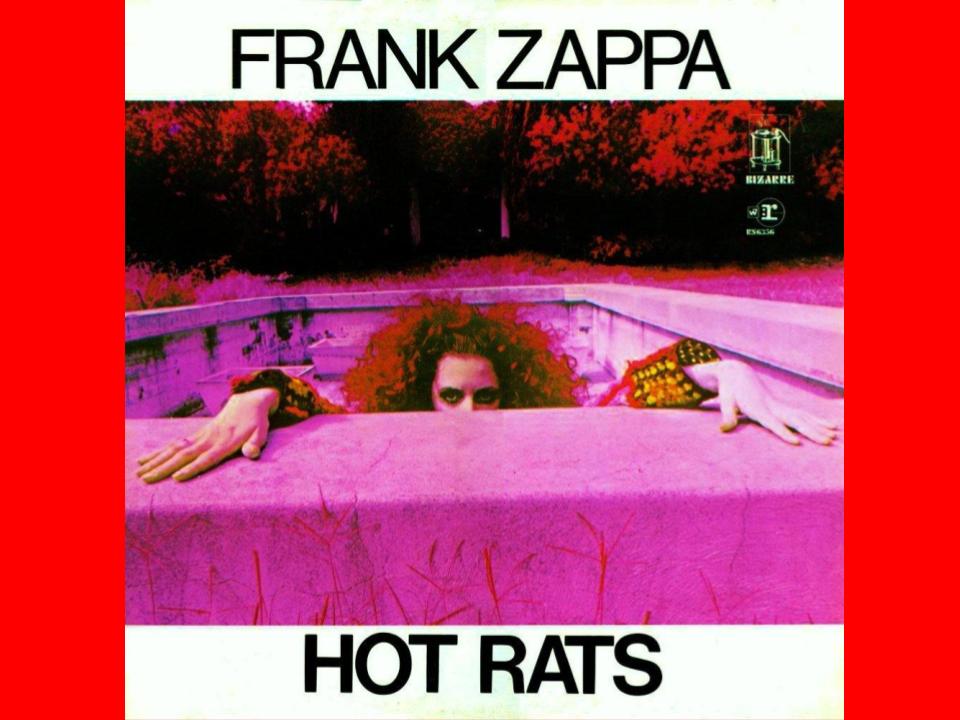

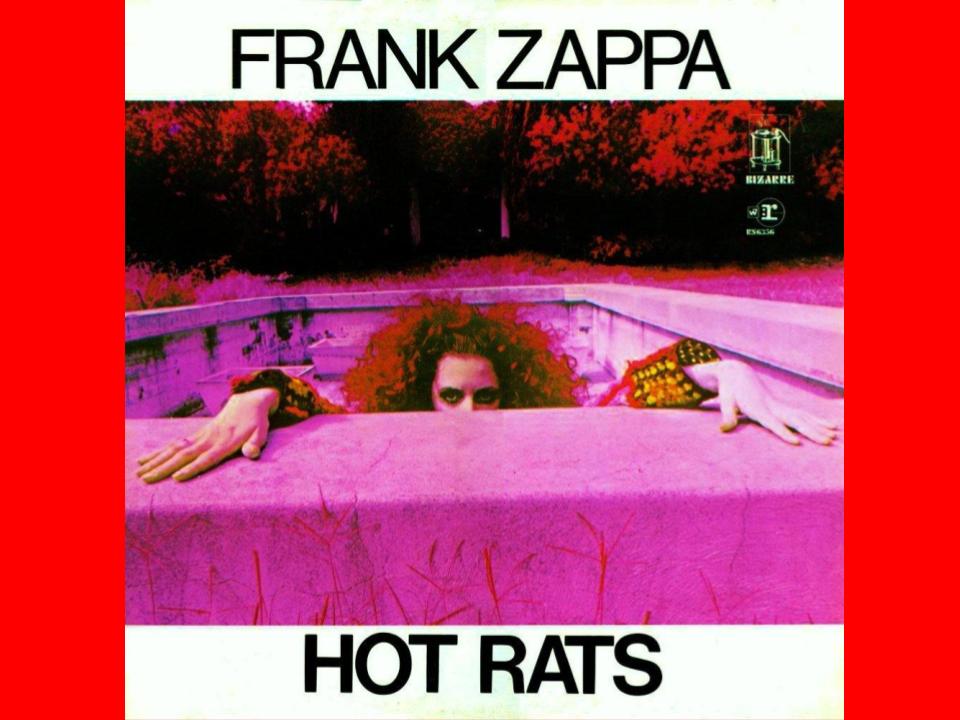

Zappa’s covers are authentic products of US popular modernity, brash, chaotic, multi-layered, trashy and ambitious. They are dada brut. The album covers query the conventions of representation, specifically rock representation, as it crystallized in the 1970s and onwards, in much the same way as dada visual practices queried art conventions as they gelled in the late teens and 1920s. As well as collage and photomontage, there are plenty of photographs on Zappa album covers. These are frequently distorted by photo-specific techniques, turned into drawings, solarised or treated in some way. The recuperated version of such visual culture is, of course, the solarised or psychedelically tinted image, which is an effort to emulate drug visions. But Zappa, unlike the drugged up hippies, did not get ‘off his head’ or ‘off his face’. He stuck resolutely with some sort of head and face, a nosy, curious one.

The dog and the dog’s nose appear in various ways on the covers throughout Zappa’s career, signs of something primitive, instinctual, doggone dirty in Rock ‘n’ Roll. And if we think specifically of recorded music, it becomes clear that the dog was there at the start. Nipper on the logo of various labels, Berliner Gramophone, Deutsche Grammophon; RCA Victor, His Master's Voice, EMI and so on.

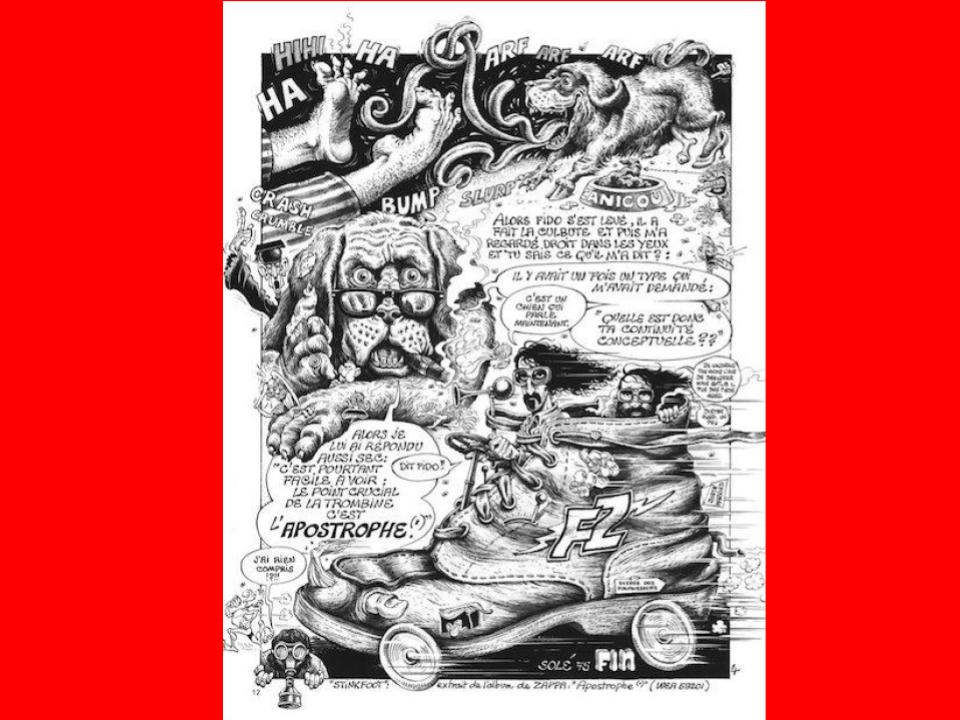

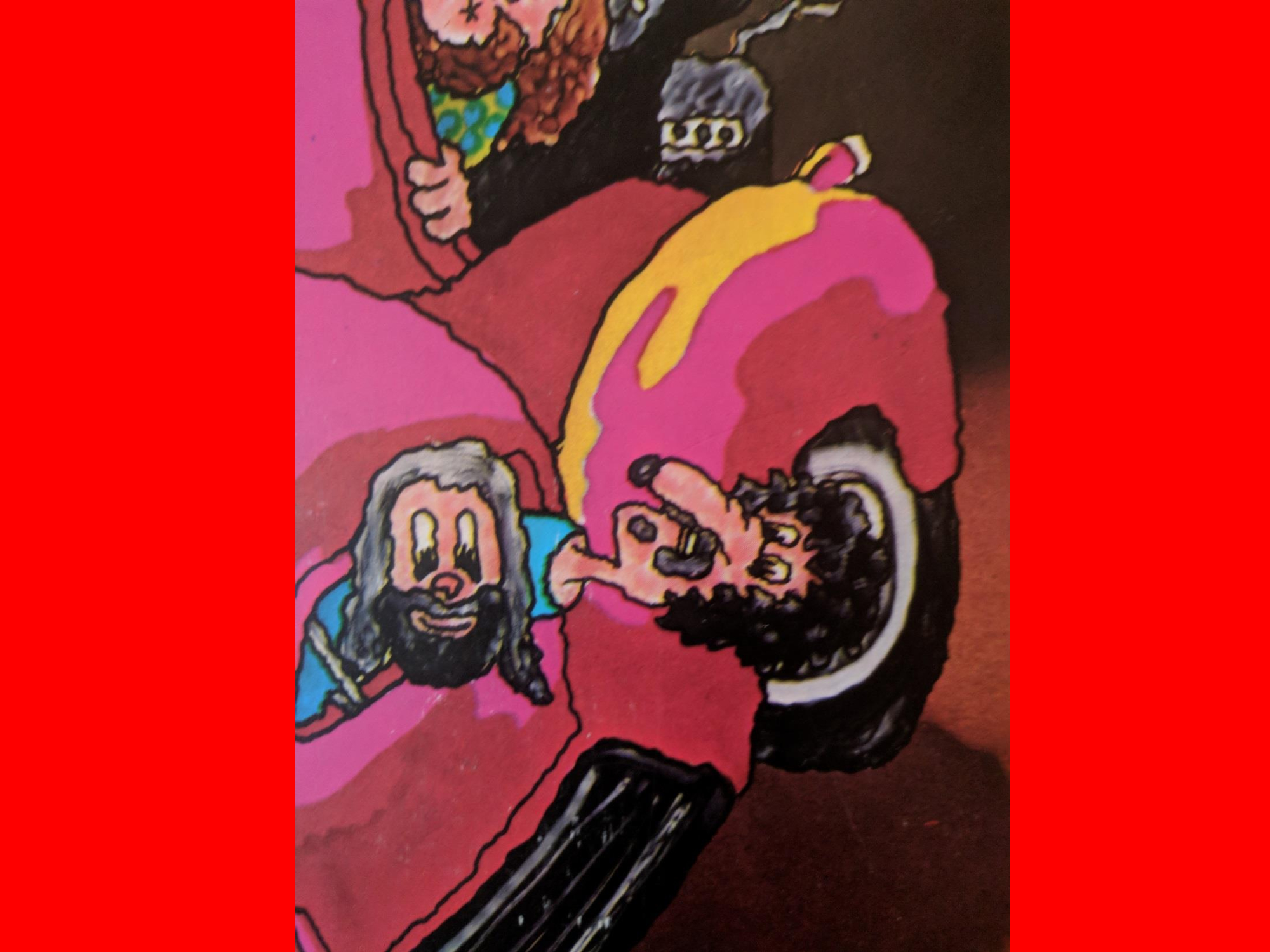

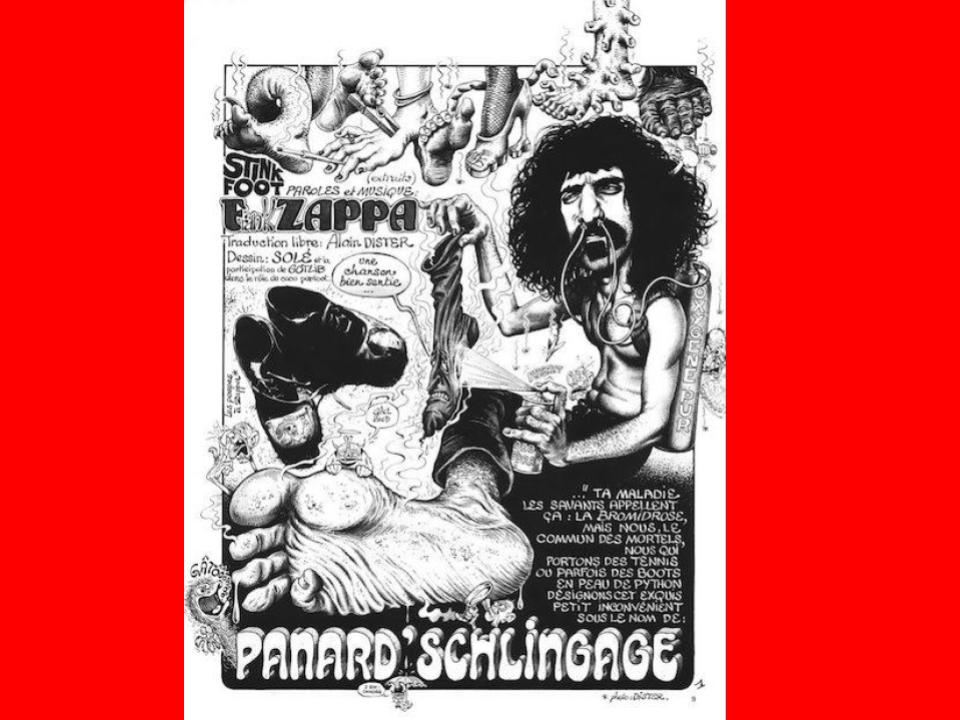

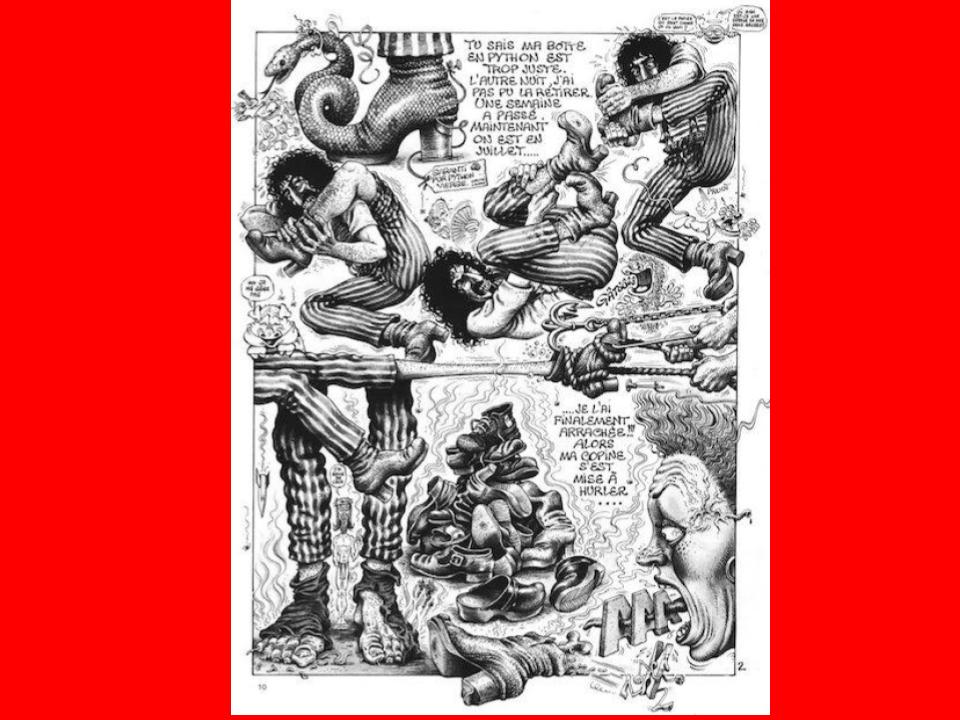

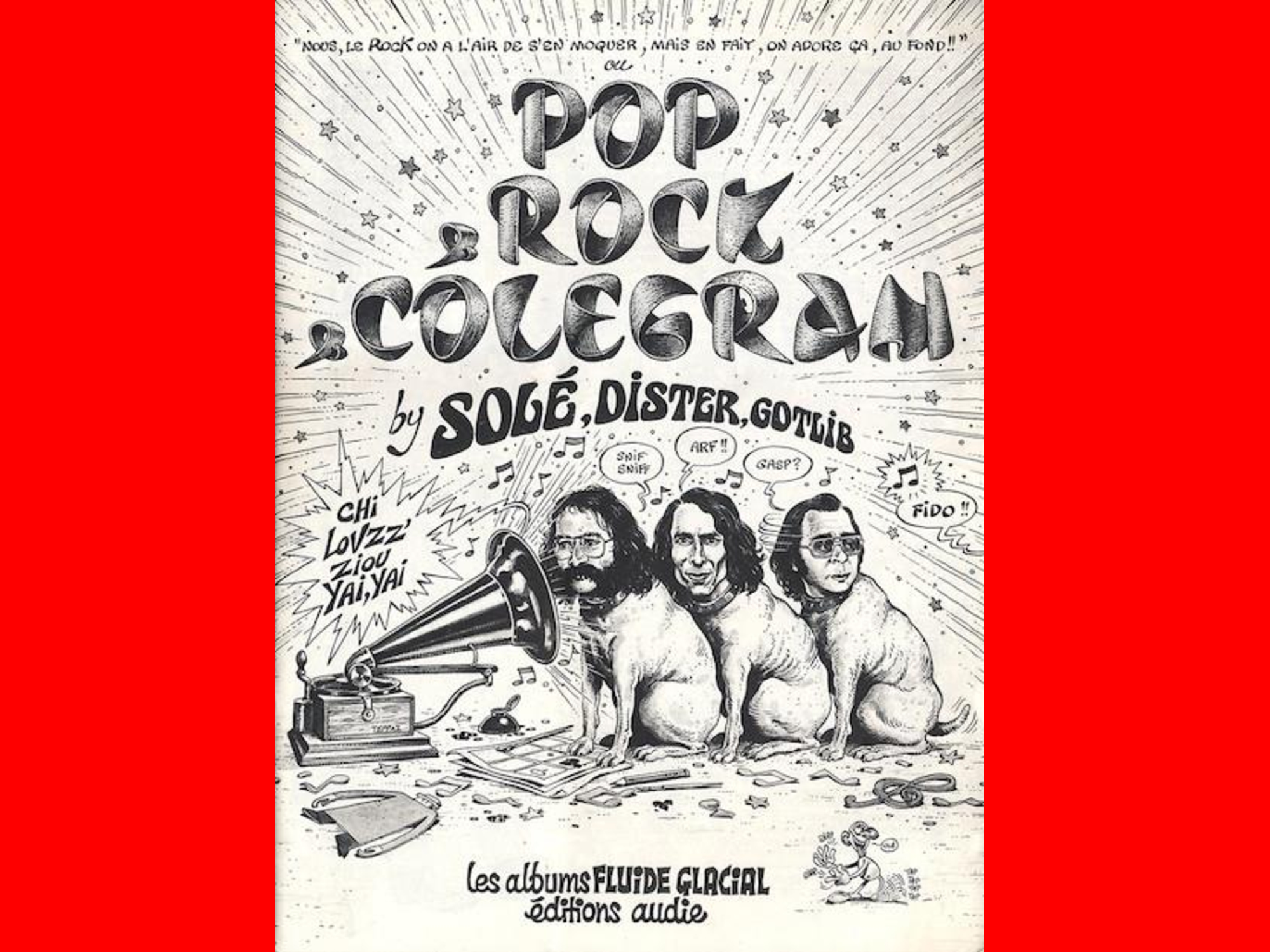

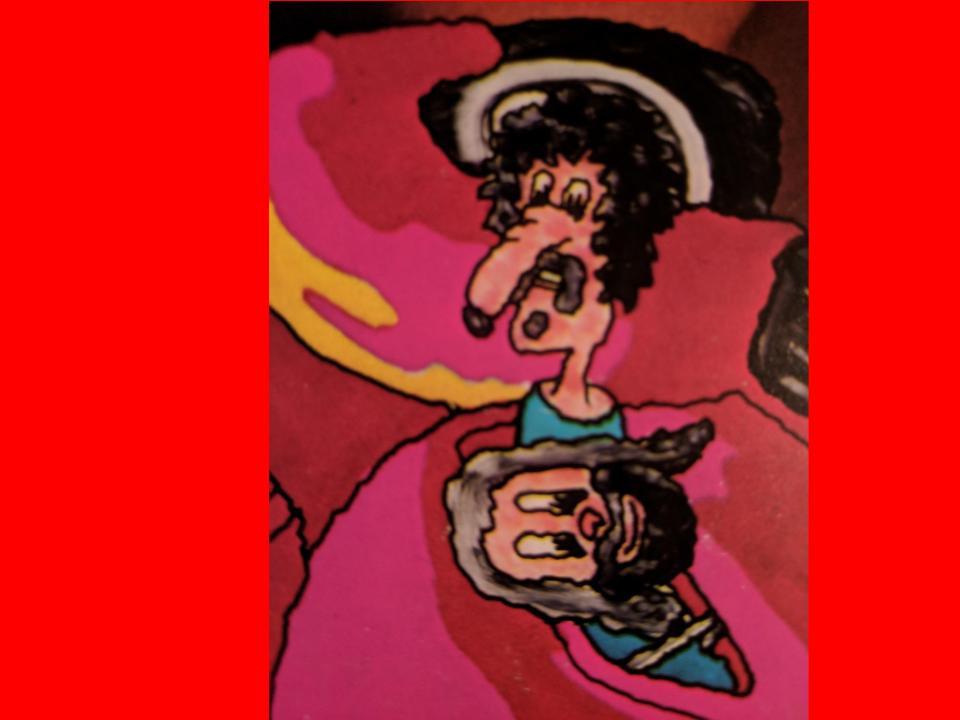

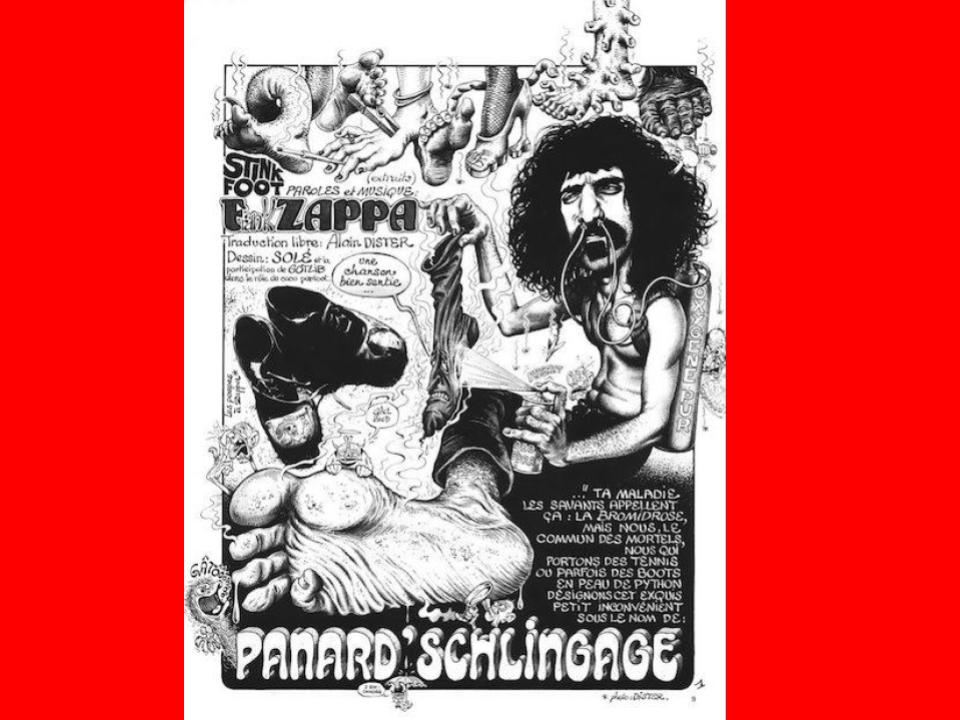

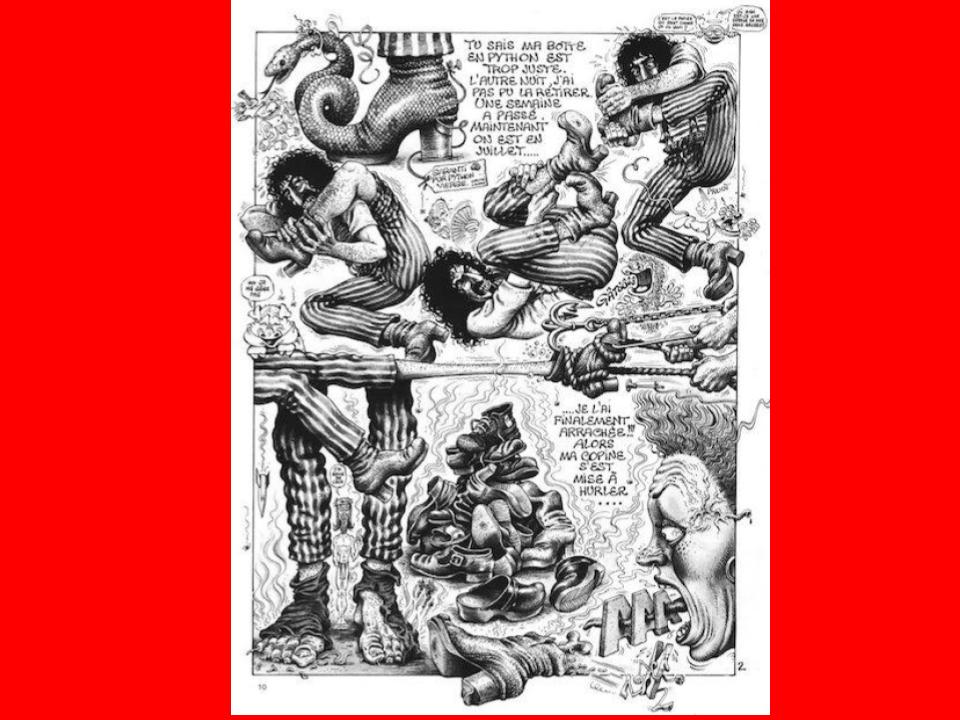

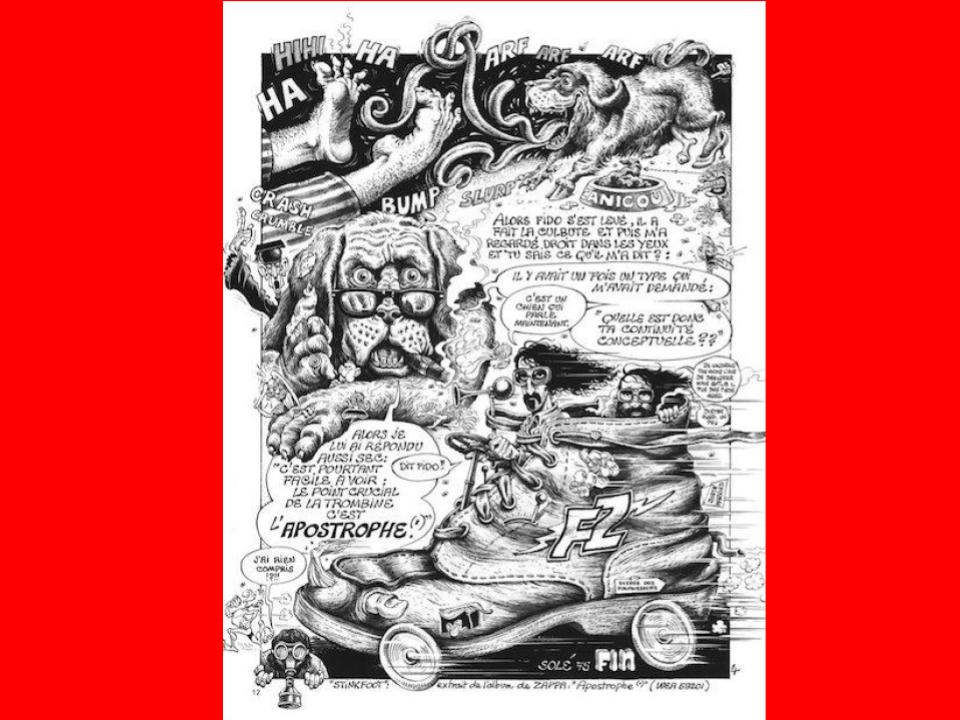

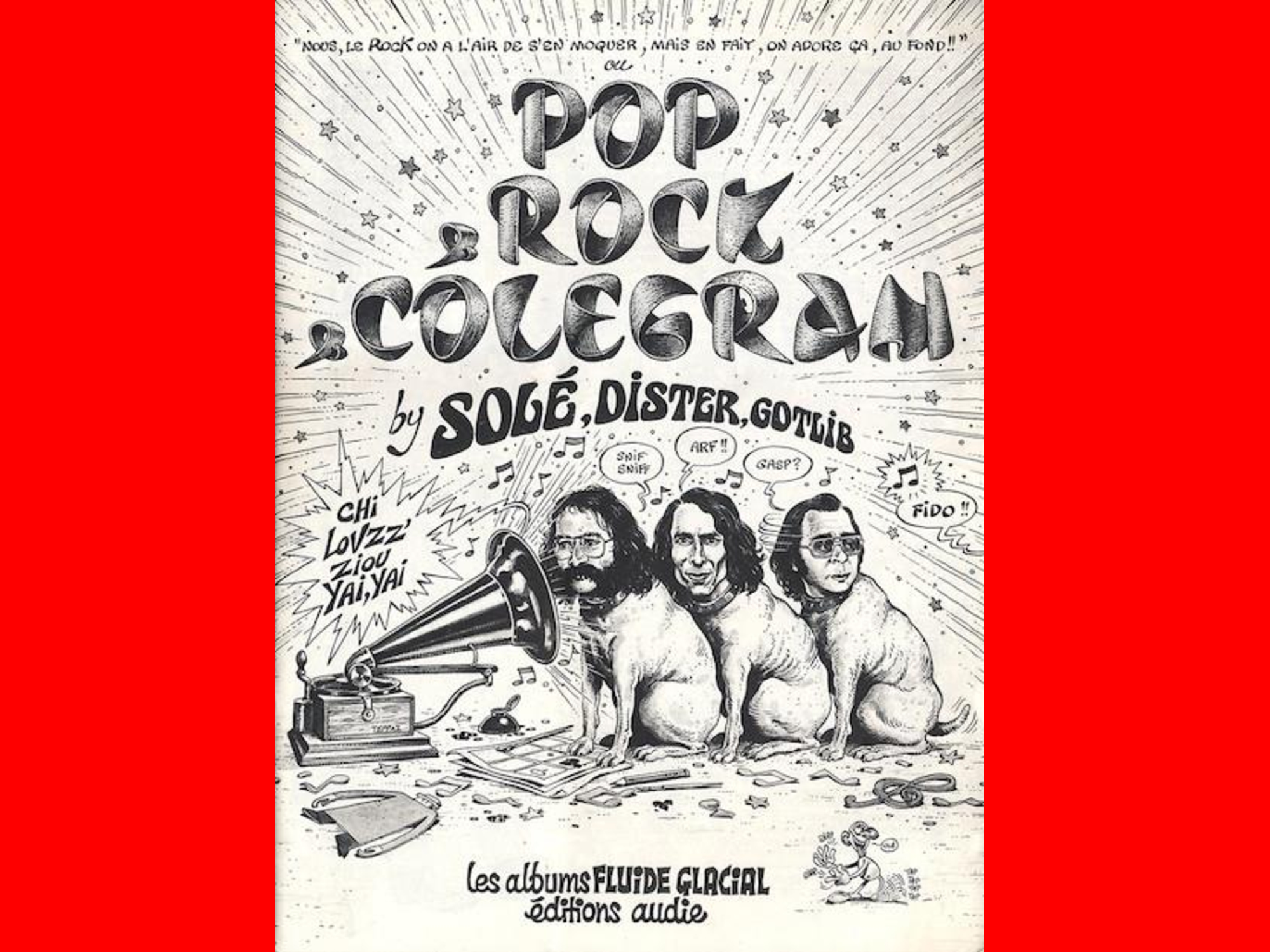

This dog’s curious expression, cocked head, is seen as a sign of fidelity, of the truthfulness of the recorded sound to its original. The counterculture of the 1970s infused the gramophone dog with another meaning. There are some comics from France, published in Fluide Glacial, from 1975-1978, by illustrators Marcel Gotlieb (or Gotlib) and Jean Solé, who illustrated songs from popular bands such as The Beatles, Roxy Music, Pink Floyd and Zappa. Here is their version of Zappa’s ‘Stink-Foot’, translated by Alain Dister. And here is their self-representation, as a series of Nippers, sat before the gramophone, listening to The Beatles, but, rather than obedient, faithful and engaged, they appear fully libidinal, distracted, with the tail of the one at the back erect, pulsing and expressive: arf, sniff, gasp.

This dog’s curious expression, cocked head, is seen as a sign of fidelity, of the truthfulness of the recorded sound to its original. The counterculture of the 1970s infused the gramophone dog with another meaning. There are some comics from France, published in Fluide Glacial, from 1975-1978, by illustrators Marcel Gotlieb (or Gotlib) and Jean Solé, who illustrated songs from popular bands such as The Beatles, Roxy Music, Pink Floyd and Zappa. Here is their version of Zappa’s ‘Stink-Foot’, translated by Alain Dister. And here is their self-representation, as a series of Nippers, sat before the gramophone, listening to The Beatles, but, rather than obedient, faithful and engaged, they appear fully libidinal, distracted, with the tail of the one at the back erect, pulsing and expressive: arf, sniff, gasp.

Back to Zappology

Get you back Home

This dog’s curious expression, cocked head, is seen as a sign of fidelity, of the truthfulness of the recorded sound to its original. The counterculture of the 1970s infused the gramophone dog with another meaning. There are some comics from France, published in Fluide Glacial, from 1975-1978, by illustrators Marcel Gotlieb (or Gotlib) and Jean Solé, who illustrated songs from popular bands such as The Beatles, Roxy Music, Pink Floyd and Zappa. Here is their version of Zappa’s ‘Stink-Foot’, translated by Alain Dister. And here is their self-representation, as a series of Nippers, sat before the gramophone, listening to The Beatles, but, rather than obedient, faithful and engaged, they appear fully libidinal, distracted, with the tail of the one at the back erect, pulsing and expressive: arf, sniff, gasp.