Madness & Art

This paper on MADNESS was delivered by Ben Watson to Brian Catling's Ruskin College students in Oxford at 4.30pm on Tuesday 30 October 2001, part of Catling's "Art & Madness Circus".

In a preliminary sketch for Das Kapital, written between 1857 and 1858 and later published under the title Grundrisse, Karl Marx wrote that when money is spent on fulfilling a human need and a commodity is consumed, it falls out of the economic process. This is the positive relationship of exchange value to use value: money's ability to fulfill a human need. The negative relationship is where money itself becomes the object of consumption, ie where the abstract need for money drives social and historical development, and exchange value dominates over use value. Then the seeming rationality of exchange value becomes 'madness; madness, however, as a moment of economics and as a determinant of the practical life of peoples' [Karl Marx, Grundrisse, 1857, first published in Russia 1939/41, in Germany 1953; translated Martin Nicolaus, London: Penguin, 1973, p. 269.] This madness which Marx foresaw is what we're living through now: a world in which the rationalised profit system produces an insane world - one of alienation and waste, mass starvation and infinite war.

Modern art has long had a direct relationship to madness, manifest since the romantics first rebelled against rationalism. In their polemical Lyrical Ballads of 1798, Coleridge and Wordsworth rounded up a posse of mad persons to chill the gentle reader: the Ancient Mariner with glittering eye and skinny hand, plagued by fiends, the female vagrant, the mad mother, the idiot boy on horseback flourishing a bough of holly. Nevertheless, the stomping ballad metres they employed, though a vulgar retort to Augustan classicism, were communitarian and winning. Madness as integral to artistic medium itself only became a technical tool in the hands of the dadaists and surrealists. Today, Modern Art in both its false and true forms has an immediate and necessary relationship to madness.

For the modern art critic, Marx's unblinking view of the irrational end-result of the bourgeois ratio - the "reason" which Thomas Hobbes likened to accountancy [Leviathan, London, 1651, Part I, Chapter V, Paragraph 4] - is a crucial orientation. Unless you understand the madness of the capitalist system itself, modern art's crazy response is incomprehensible.

In Grundrisse, Marx criticizes conventional history writing. He turns chronology inside out. He insists that history may only be understood by consciously applying the most recent analytic ideas. In that spirit, I'd like to begin my account of art and madness with a poem that was written two weeks ago by J.H. Prynne. If this paper were to sketch a chronological account of madness that began with Pan and Circe, and went on to mention Apuleius, Nebuchadnezzer, King Lear and Christopher Smart, finally arriving at the twentieth century with Antonin Artaud, Sylvia Plath and Julian Cope, I'm sure I'd bore everyone stiff. Such a chronological survey naturalises a concept like madness and seives history with a fixed mesh: it will only catch the usual fish. By looking at one of the latest technical assaults on the bourgeois ratio, we may be able to tear the fabric of our received ideas and let in some artistic deepsea monsters worthy of a national population which has just witnessed the wonders of The Blue Planet series. Here's some recent J.H. Prynne:

Profuse reclaim from a scrape or belt, funnel do

axial parenthood block the mustard dots briefly

act forward, their age layer for layer in this

tied-off accession. Appellate at dictum at

its debit resonance fixing prolusion, optic rage

performs even dots right now. This is the top

passion play and counted out for renewal patch,

allergic his dispute braving off. Make a dot

difference, make an offer; these feeling spray-on

skin products are uninhabitable, by field and stream.

Tell us, only for as many as crowd in through

the door to the diluvium, the romance of a new

organic dyscrasia vibrato fretting its early bits

on release on ambit. Early grief, late woe ahead.

This poem appears on the first page of Unanswering Rational Shore, a pamphlet published by an obscure Glasgow press named Object Permanence - "If you'd like to eyeball a 20-page verbal pie that dissolves the difference between nouns and verbs, and speaks of romance and international politics in a single, Kant-defying, garlic-aroma breath (ie Unanswering Rational Shore by J.H. Prynne), send a cheque payable to Peter Manson for £2.50 (P&P included) to Peter Manson Object Permanence, Flat 3/2, 16 Ancroft Street, Glasgow, G20 7HU. Don't forget to include your own address. Sonnet the alarum-scarum!!" - and mailed by the reclusive cult poet to a handful of correspondents. My envelope was franked at Gonville and Caius College on 15 October.

Like Jean-Michel Basquiat or a Free Improvisor, Prynne begins by responding automatically to a random, arbitrary scrap of cultural material. 'Profuse reclaim' is the kind of lordly yet seemingly meaningless phrase that might spring to mind after witnessing a Shakespeare play (or indeed writing a 140-page essay on one of his sonnets). Like any manifestation of the unconscious, the two words condense many ideas. It spoonerises as 'refuse proclaim', which settles into neither of the common pronunciations of those six letters - refuse (to reject) or refuse (garbage). To 'refuse proclaim' would be to reject public rhetoric. Then there's 'refuse reclaim', suggesting recycling. Prynne is closer to the ragpicker or scavenger than the politician. But there's also 'profuse proclaim' suggesting prodigious or excessive verbiage.

This conflictual two-word beginning operates like a 'cell' in a Cecil Taylor piece, a tiny scrap of material - a mere three or four notes - which packs in contradictions which the improvisor can explicate at length. The Oxford English Dictionary defines 'reclaim' as 'to win from vice or savagery, to civilise'. Such reclamation might be derived 'from a scrape or belt', which sounds like the day's residues as described by Freud: the unnoticed observations of the day before which the unconscious uses to pitcture its wishes. It'd be easier to acceot 'from a scrap or belt', because then both options would be drawn from the a set of nouns. 'Scrape' is more verb-oriented than 'scrap', implying an action. It makes 'belt' look strange, less something to hold your trousers up than a verb as in to 'belt someone' or strike them. A scrape might be a medical skin sample or a risky situation.

With 'funnel do/axial parenthood block the mustard dots briefly/act forward' the ambiguity about parts of speech achieves complete gibberish. If anyone can parse this sentence they're a genius, or more likely lying. Where's the verb? 'Do' ought to be a verb, but it doesn't seem in the right place, maybe it's a noun, as in 'dog do'. Many of Prynne's effects in his current poems play on the distinction we make between singular and plural in nouns and verbs, where the 's' changes places - 'the crow flies' but 'the crows fly'. You find yourself going from word to word, attempting to find any word that could serve as a verb for an assumed subject made of a string of appositional nouns. Is 'dots' what 'the mustard' does, or is it the plural of the noun 'dot'? If I actively 'dot the surface' I've made some 'dots'. In Marx's terminology, 'dots' is my objectified labour. If it's mustard-coloured, I may be an Australian aborigine making a painting for purchase by a tourist, and there may also a trendy nod to Damien Hirst's 'spot' paintings. Prynne's free-association is open-ended, nothing is blocked out due to partisanship or taste.

A string of non-syntactical elements resembles black-magic spells in horror films - 'funnel do axial parenthood block' - though the 'the' brings in something more domestic. Compared to what has preceded, 'their age layer for layer in this/tied-off accession' at least sounds like sense.

Prynne keeps the reader tantalised by the idea of some urgent political or cultural message, but remains suspicious of any overarching discourse or system of certification. He refuses to restrict himself to any known discourse. Functional communication would suggest submission to an oppressive system. In interpreting Prynne we need to jettison what we learned in 'A' Level English - find out what the poet is 'really saying' and by doing so upgrade our vocabulary and set of cultural references. We have to approach Prynne as we would an abstract or conceptual painting, or a piece of music. Instead of seeing them as merely bamboozlong, one can find the sudden jumps to a word drawn from a completely unlikely area of language as exilarating, a bravura demonstration of imaginative freedom, defiance of cliche, like the extended intervals of guitarist Derek Bailey's improvised responses to his colleagues' notes. We can register these effects, pool our responses, use the artwork to interrogate the supposed normality of systems that do work. Analogies to modernist devices in other media can be helpful. The ambiguous way 'dots' won't lie down as either a plural noun or a singular verb, making it a pivot, resembles the way cubist paintings often centre the design on an optical pun - a shadow that may be either convex or concave, an overlap which contradicts proper perspective.

Prynne's poems contain suggestive formulae for anyone pondering movements in Modern Art. 'Make a dot/difference ...' could be a tachiste or brutiste manifesto, imploring the reader to give up representation, and return to aboriginal dot-making, where everyone's personal mark would be valued without the hierarchies of genius and fame which structure post-renaissance art-appreciation. When Guy Debord wrote appreciatively of the chimpanzee paintings exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, people thought he was being ironic. Actually, anyone who follows Asger Jorn and COBRA into the real of automatic gesture - this is where Captain Beefheart is now, I think - will appreciate that in making these marks, the artist is establishing some pre-cultural, animal truth. From this perspective, watching a recent TV-studio audience laugh at film of elephants making paintings by using brushes held in their trunks was painful: the audience were laughing at their own animal selves, infinitely more full of potential and beauty than their own cramped so-called 'civilised' ideas. As Captain Beefheart asked: 'Space-age couple/Why do you hex that magic muscle?'. [Captain Beefheart, 'Space-age Couple', Lick My Decals Off, Baby, Bizarre/Straight, 1970, Reprise K44244; 1989, Rhino R2 70364]

Yet Prynne cannot simply promote tachiste 'dot making' as a cultural strategy. His phrases are immediately tainted by the slimy and collusive manoeuvres of commerce, the bland addresses to the economically solvent which mask inequality and exploitation (the French version of 'reclaim', rclame, means 'sign' or 'advertising'; as used in English, it means slightly bogus fame as the result of publicity) - 'make a dot difference, make an offer'. How can Modern Art prevent itself becoming just another 'promotional device'? [Frank Zappa, preamble to 'Punky's Whips', Zappa In New York, 1977] 'These feeling spray-on/skin products are uninhabitable'. Even as he is addicted to the pleasure of manipulating trash into grotesque hieroglyphics, the postures available in an exchange economy disgust the poet. Anger at commercial hypocrisy is tapped as an energy, used to crumple the words.

The book's epigraph is -

lo mismo

Detail from Inscription outside Palacio Real, Madrid

lo mismo

- fourteen letters: a compacted lettrist sonnet made of Francesco de Goya's despair of finding anything other than the Spanish words for "the same" to title his endless pictures of the horror of war. Inside the book, each sonnet is likewise divided into two stanzas of seven lines each; and the booklet itself consists of two sets of seven sonnets. Unanswering Rational Shore presents each poem as of it could be a single line of a macro-poem in identical format. When Karlheinz Stockhausen proposed that every note in a composition could itself be a compressed symphony, or James Joyce said that Finnegans Wake could be a story in Dubliners, both broached the same dizzying, infinitely-receding fractal universe. In Prynne's poetry we aren't being given assurance of the poet's bourgeois-individualist mastery of emotion and nature, but experiential simultaneity of cosmic, geological, biological, social and individual levels.

Diluvium is what is left by a flood; those who 'crowd in through/the door' are presumably us poor suckers, attempting to interpret the secret code. 'Dyscrasia' is bad temper; 'the romance of a new/organic dyscrasia vibrato fretting its early bits/on release on ambit' seems to be a surly comment on the lyric gesture itself, its vocabulary designed to include youths who turn to rock music and guitars for self expression. It's a fancy way of describing lyrical expression as immature and oversexed (a previous phrase used by Prynne to describe pop music is 'sex buttered up for the instant'). The gloomy prognosis 'Early grief, late woe ahead' is a dark warning about the poetry lying in wait for the reader in the next pages. It's hard to say 'late woe ahead' without slipping the tongue over to 'late woad ahead'. I read in this an inkling of a post-commodity, communist tribalism, an end to the substitutions of the exchange exconomy, blue dots of woad marking the skin: 'across the bload-soaked Euston Road, a revolt against bourgeois civilisation broods and beckons'.

This kind of free interpretation of Prynne's lyric seems to upset the Cambridge poets who have adopted Prynne as their private magus. However, as with the academic approach to Finnegans Wake, commentators like Drew Milne [Drew Milne, 'Speculative Assertions: Reading J.H. Prynne's Poems', Parataxis: Modernism and Modern Writing, 10, 2001, pp. 67-86, available from Parataxis Editions, c/o Drew Milne, Trinity Hall, Cambridge, CB2 1TJ ; for a rather less dim view of Prynne's revolutionary playfulness, see Peter Middleton, 'Dirigibles', Quid, 8ii, 2001, pp. 28-49, available from Keston Sutherland, Gonville & Caius, Cambridge, CB2 1TA ] seem to miss the point. It is not about trying to 'interpret' Prynne, to bend his doxa round to one's own dubious point of view, but an attempt to recognise the gigantic pleasure and relief of encountering his texts, the permission it gives to the productive verbal unconscious. What Frank Zappa said of his own project/object - however distasteful such a low-cult reference may be to Cambridge academics - applies to Prynne's poetry: it is a 'special art in an environment hostile to dreamers'.

If Prynne's poems refuse to engage with the 'public sphere' defined by Juergen Habermas - they're hardly applications to the post of Poet Laureate - then that may be because it doesn't agree with bourgeois definitions of the political as they are scribbled on smoke clouds billowing from the clay pipes of men in eighteenth-century coffee-houses. The transcendental individualism of academic interpretation demands that the canonic author pursue an exemplary life. However, like Joyce's texts - and, as argued by Robert Bond in his recent PhD, like Iain Sinclair's - Prynne's poems demand collective interpretation, use and abuse. They cannot be understood by an isolated reader. They are a contribution to a revolutionary culture, critical of capitalist property relations and aiming to free the unconscious from the bonds of privatisation.

I see J.H. Prynne as the poet laureate of Mad Pride. He is our Isidore Ducasse, our Comte de Lautréamont. We swim in his texts and try to understand what we experience, much as Walter Benjamin tried to understand marijuana, or the character David Hump in Iain Sinclair's Landor's Tower tries to understand ketamine. If we stumble on perceptions or bon-mots that tell us about the world and so suit our politics, all to the good. If Drew Milne is worried by the way Prynne's poetry forces the critic into a self-revealing or partisan positions, then he should stick to explicating poets who aren't rearranging subject/object relations. Collective cultural production means breaking with the universal model of the 'perfect citizen' beloved of bourgeois idealogues from Immanuel Kant to Tony Blair: in our refusenik co-operative phalanstery, precisely because there is no economic exploitation or hierarchy, we have places for unlikely characters - lyricists, agitators, philosophers, drunkards and mad people. 'Specialisation' is only a curse when it's part of the capitalist division of labour; we can embrace Prynne as grist to the mill, the first-water fire spirit for anyone dealing with words.

Wordsworth and Coleridge wrote about the mad and dispossessed. The dadaists and surrealists risked becoming mad and dispossessed themselves. Prynne's texts makes his readers feel as if they are mad and dispossessed. As I've said, one of the techniques he uses for achieving this is concocting verbal series which make the distinction between nouns and verbs ambiguous. Whether consciously Marxist or not (Prynne refered positively to the Marxist linguist Valentin Voloshinov in his essay Stars, Tigers & The Shapes of Words [William Matthews Lectures at Birkbeck College, 1992, p. 60, n. 158], but seems to prefer latterday proselytisers such as Mao, Debord or John Barrell to the real thing), this destabilising effect is most interesting. Marxists recognise that reification, the treatment of human products and relations as 'things' rather than 'active processes', is one of the most insidious effects of bourgeois ideology. Prynne's dissolution of the noun into the verb, the intimation that things are the result of process, is highly dialectical. Unlike language poetry and its postmodernist "free choice" justifications, Prynne's poetry is not about the transcendent individual, it applies the Revolution of the Word called for in the journal Transition between the wars: a technical operation on language which acknowledges and promotes progressive developments in the material base. This is not to use Marxism as a metaphor. Addressed to the Centre for Research in Poetics 'Talks' series on 17 October 2001, Andrea Brady's '100 Days, Poetic Pathos and Political Apathy' denounced the merely metaphorical Marxism of the Language School poets Bruce Andrews and Steve McCaffrey, who declare that normative grammar is 'a machine for the accumulation of meaning seen as surplus value'. For Brady, the fact that several leading US 'avantgardistes' - Ron Silliman, Marjorie Perlof - have applauded Bush's military response to the 11 September attack on New York indicts the liberal individualism and nationalism which lurks behind American poetry's 'deconstruction of the subject'.

Am I dragging in Marx here by the short and curlies?

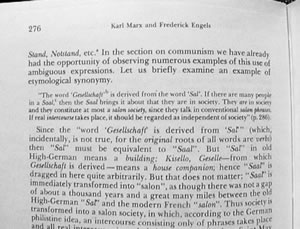

'The original roots of all words are verbs' said Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in The German Ideology in 1846 [first published in Russia 1932; translated W. Lough (pp. 19-92), Clemens Dutt (pp. 94-451) and C.P. Magill (pp. 453-540), London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1976, p. 276]. The statement anticipated James Joyce's phrase 'in the beginning was the rhythmical gesture' [Joyce was using a retort to St John formulated by Marcel Jousse, according to Mary and Padraic Colum, Our Friend James Joyce, New York: Doubleday, 1958, p. 87]: both Marx and Joyce defy the reification of nouns and prefer to emphasize human activity.

The grammatical distinction between nouns and verbs is an analytic one: a grid imposed on actual usage. Genuine spoken utterance slips between nominal and verbal usage of phonemes, as the double entries for words as both nouns and verbs in the OED makes clear. However, the distinction has nevertheless been around long enough to have become embedded in physiology. According to Dr Donald McKendrick, who gives medical advice in the pages of Saga (a magazine designed to sell insurance schemes and holidays to elderly people), 'there are different nerve pathways for nouns and verbs'. When the language centre of the brain is damaged - an area which in right-handed people is invariably on the left side of the brain - nouns are the first words to go. Dr McKendrick advises people suffering from Alzheimer's who cannot think of a word to try thinking of a verb rather than a noun - 'I don't know what it's called, but I would use it to paint a house'. Of course, 'it' is called 'paint'' [Dr Donald McKendrick, 'Think Verb, Not Noun', Saga Magazine, October 2001, p. 145].

Words which can serve as both nouns and verbs are usually carried by one nerve pathway or another, depending on their grammatical function. This may explain why Prynne's ambiguous phrases render an interesting affect, a kind of doubled-up sensation like an optical illusion. Of course, one can imagine a criticism which would be that what Prynne is doing is 'unnatural'. This would be similar to conservative objections to Cubism: by naturalising a cultural convention, such criticism seeks to elevate artificial conditions beyond reproach. Prynne is not delivering a sermon in a readymade language or performing a virtuous task within a predefined morality. Capitalism is moving too fast and breaking too many boundaries for such operations to be anything but reactionary. To resist capitalism, we must be as spontaneous and self-defining as its most harmful agents.

Prynne is not preaching, but playing at the fringes of cultural potential - which is why his booklet is named Unanswering Rational Shore. What is the limit of our rational comprehension, and if reason doesn't echo back what we shout at it, how do we know that rationality stops there? The last poem in the pamphlet begins:

All the fun of the pit gets well and then better, sand spun off as yet to bind promise to tap up one clock via another ...

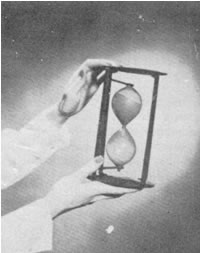

The

words evoke such themes as fun-fairs and Hell, Operations Desert Storm and

Infinite Justice, time as sand running through the hour glass, and

the stomach-twisting comparative clocks of Einstein's Relativity. The hourglass

stomach of Nicolas Lane, referenced in the first paragraph of Sinclair's White

Chappell Scarlet Tracings and which brought pomo-beat novelist and nominal

occultist Charlie "Bad Boy" Mitten into being (Bad News Mutton in Iain Sinclair's

Landor's Tower) is also invoked. Yet despite such triggering of momentous

concepts, with Prynne's poetry we are on the beach, or playing in a sandpit.

One meaning of 'shore' relates to the word 'sewer', and describes the no-man's

land by the water-side 'where filth was allowed to be deposited for the tide

to wash away' [OED]. This shore would be a kind of social diluvium. As Devo

said in one of their first interviews to the British rock press, 'we are simply

playing in our own poo-poo'. Like Devo and like COBRA (the art movement Asger

Jorn was involved in before the Movement for an Imaginary Bauhaus), Prynne

seeks a return to the early, unsplit stages of a human being's acquisition

of knowledge, where play is not passive consumption, but activity and production.

and

the stomach-twisting comparative clocks of Einstein's Relativity. The hourglass

stomach of Nicolas Lane, referenced in the first paragraph of Sinclair's White

Chappell Scarlet Tracings and which brought pomo-beat novelist and nominal

occultist Charlie "Bad Boy" Mitten into being (Bad News Mutton in Iain Sinclair's

Landor's Tower) is also invoked. Yet despite such triggering of momentous

concepts, with Prynne's poetry we are on the beach, or playing in a sandpit.

One meaning of 'shore' relates to the word 'sewer', and describes the no-man's

land by the water-side 'where filth was allowed to be deposited for the tide

to wash away' [OED]. This shore would be a kind of social diluvium. As Devo

said in one of their first interviews to the British rock press, 'we are simply

playing in our own poo-poo'. Like Devo and like COBRA (the art movement Asger

Jorn was involved in before the Movement for an Imaginary Bauhaus), Prynne

seeks a return to the early, unsplit stages of a human being's acquisition

of knowledge, where play is not passive consumption, but activity and production.

As an example of the reifying effect of the nominalisation of verbs, it is instructive to note historical uses of the word 'sign', since it was via structuralist study of 'the sign' that the Kantian notion of significance as a transcendental, sealed-off, quasi-divine system was smuggled back into desanctified philosophy and the secular humanities. All the first uses of the noun 'sign' in the OED are coupled with 'make' and refer to an intended gesture: the root of the word is in social action. It is with Bishop Berkeley's Theory Of Vision Vindicated in 1733 that the earliest description of language as 'a great number of arbitrary signs' surfaces: signs without a specific, class-specific agent [Bishop Berkeley, The Theory Of Vision Vindicated And Explained, London: 1733, para. 40; Philosophical Works Including The Works On Vision, edited M.R. Ayers, Melbourne and London: Dent, 1975, p. 241]. Berkeley's apology for religion required an all-out assault on materialism, and his Christian concept of the sign - a mark imposed on things by God or Man from the independent and unsullied realm of ideas - is a statement of early-bourgeois Idealist Dualism which also fed into Kant and Saussure, and helped source the whole presentday colic of post-structuralism and post-modernism. Berkeley's aggressive defence of religion (aka his episcopal stipend) has an eerie similarity to the phrases spouted by humanities professionals when justifying the deflected enlightenment and diluted politics incumbent on academic tenure.

To return to the title of Prynne's pamphlet: Unanswering Rational Shore. One of the definitions of 'rational' is the breastplate of the Jewish high-priest, an accessory adopted by early Christian bishops before the institution of the stole. The Hebrew hoshen - meaning 'oracle' - was translated in the Vulgate by the Latin for 'rational', meaning 'thinking' or 'reasoning'. This is the kind of fact - a historical repudiation of today's binaries - which causes a deconstructionist like poet Steve McCaffery to dive into the whirlpools of relativism, but there is a way out of the bourgeois polarity between hard science and poetic or religious drivel. The historical materialist often discovers that when the root of a word - its actual usage in history - is investigated, we come down not to the hard rock of Heideggerian authenticity, but to the quivering jelly of religion.

What is this jelly, ubiquitous, unctuous and scented? Marx explained the rise of priests and religion as class society's way of dealing with surplus value. Temples were first erected to house surplus grain and plundered booty. The Jewish high priest could be both oracular and rational, because what he said was an order you could not disobey. The Marxist contends that the orders coming from those who run the capitalist exchange system are 'rational' in precisely this way: they express power relations rather than a relation to truth. Of course, Friedrich Nietzsche and the post-structuralists concur here, but lacking any concept of determinate social class, and still less any class orientation that might provide a basis for a superior rationality, they throw themselves into a convenient froth of nihilist relativism. Prynne's historical materialism refuses such trendy bollocks, and instead allows the sleuth - dogged in pursuit of a material substructure revealed by poetic free association - to descry the irrational whole. Prynne's poems show that it is commodification - the freezing of our activity into mere things - that causes life and joy and ends-in-themselves to look like avantgarderie and madness.

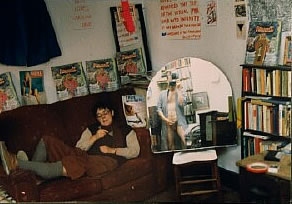

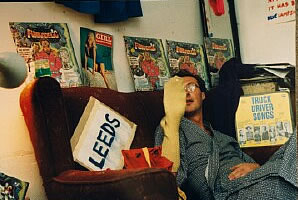

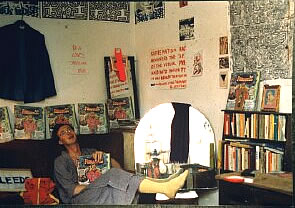

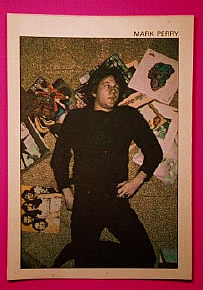

I am aware that, especially for visual artists, what I have said and shown so far may be rather dry, a bureacratic travesty of calls for joy and madness. So I'm now going to tell you about my own bout of madness, which occurred in the years 1983 and 1984. Today I interpret my nervous breakdown as a demand for the supersession of private-property relations which was lived out individualistically, and so was out of kilter with social rationality. There has been a thaw in the political climate since the 80s - starting with the Poll Tax Riot (1991), and culminating in the anti-capitalist protests in Seattle (1999) and Genoa (2001) - so that revolutionary subject and social object don't now seem so madly bifurcated. It no longer seems so easy to dismiss madness - along with Prynne's poetry - as politically irrelevant. The eruption of Mad Pride as a civil-rights movement indicates that connections severed since R.D. Laing are now being re-articulated. At the Protest & Survive show at the Whitechapel Gallery on 2000 I noted that erect penises, previously taboo - or at least the definition of 'hardcore porn ' in the 80s - are now ubiquitous in the art world, if not obligatory. So here's my mad cock shot.

This was the climax of my domestic-madness period, shortly before being committed to High Royds mental hospital in North Leeds in 1983. I'm afraid the hard-on isn't very impressive, it was hard to keep it up while focusing the camera. My girlfriend at the time, Coraline Arrsctt, now a distinguished art historian at the Korrtolld Institute, is lying on the sofa. The Funkadelic albums - One Nation Under A Groove, with the free 'Lunchmeataphobia (Think! It Ain't Illegal Yet!)' special EP included - I found at Pound Stretcher on Vicar Lane in Leeds city centre retailing at 10p each. I spent £2 of my dole cheque and acquired twenty. I remember walking with them under my arm home to catch the bus home to Woodhouse, whistling happily. I spent six months giving them away to suitable recipients. You might have thought that it was such an unexpectedly glorious turning of exchange into use value that sent me over the edge. It wasn't. What did was a holiday in south-west France with twenty friends where everyone shared everything, including their bodies. No-one was emotionally hurt, everyone was hilariously honest, and the discussions about sex and politics were fantastic. People cried when they left to go home. It was as if we'd all fallen in love with each other collectively, broken through the privatised monad. I also learned what a real fuck could be like, truly Wilhelm Reich's 'cosmic plasmatic sensation' (not with Coraline Arrsctt, by the way - the 'BEN LOVES CAROLINE TRUE' sign on the wall was disavowal of the ensuant breakdown of a 15-year relationship). During the high point of the celebrations, neon colours popped in my head, and I had an afternoon when my heart pounded fit to burst my ribcage, and everything I looked at was edged with the kind of bright, broken, jagged patterning you find in manuscripts drawn and coloured by the Aztecs. Back in Leeds, I brought out the box of Funkadelic albums in order to provide other people with a taste of my new, multi-faceted visions. Colours seemed brighter than I'd ever seen them before. The quote on the wall is from El Lissitsky:

Suprematism has advanced the tip of the visual pyramid into infinity. It has broken through the blue lampshade of the firmament.

Which

is pretty good for a constructivist who was

subsequently bullied by Stalin into propaganda for the lie of socialism-in-one-country.

The 'blue lampshade' riff is actually a floating suprematist lyric, first

put into print by Casimir Malevich in 'Non-Objective Creation and Suprematism',

in the catalogue of the 10th State Exhibition held in Moscow in 1919 [Casimir

Malevich, 'Non-Objective Creation and Suprematism', Catalogue of the 10th

State Exhibition, Moscow, 1919; K.S.. Malevich, Essays On Art 1915-1933 Vol.

1, London: Rapp & Whiting/Andr Deutsch, 1968, p. 122]. Statements of cosmic

humanism which were popular currency and even state-sponsored under Bolshevism

were reduced to mere madness during the sloughs of Reaganomics.

Which

is pretty good for a constructivist who was

subsequently bullied by Stalin into propaganda for the lie of socialism-in-one-country.

The 'blue lampshade' riff is actually a floating suprematist lyric, first

put into print by Casimir Malevich in 'Non-Objective Creation and Suprematism',

in the catalogue of the 10th State Exhibition held in Moscow in 1919 [Casimir

Malevich, 'Non-Objective Creation and Suprematism', Catalogue of the 10th

State Exhibition, Moscow, 1919; K.S.. Malevich, Essays On Art 1915-1933 Vol.

1, London: Rapp & Whiting/Andr Deutsch, 1968, p. 122]. Statements of cosmic

humanism which were popular currency and even state-sponsored under Bolshevism

were reduced to mere madness during the sloughs of Reaganomics.

The blue shape above the sofa was not actually the broken blue lampshade of the firmament, but a cotton jacket whose blue colour seemed impossibly saturated. Likewise the day-glo pink socks, which I'd bought from a rock'n'roll stall in Brick Lane Market. They had the words "Jerry Lee" printed across a piano keyboard on the ankle. It was 1983, there was no getting away from Keith Hareng (from Malcolm McLaren's Duck Rock in-shop display), or African textiles (the piece of cloth visible in the top right-hand corner was brought back from Kenya by Caroline's sister Mary-Lou, now a successful architect married to John Carson, who teaches at St Martin's School of Art).

This sock also seemed extraordinarily yellow, like an eyeless woollen canary. On the left, perched on the sofa back, is a jar of green hair-gel I placed under the glare of an equipoise lamp. I was fascinated by the emerald glow. That's a hitching sign which had run in the rain. The red cloth shopping bag with its yellow strap and the album Truck Driver Songs - on the Starday label, and bought at another stall on Brick Lane Market, in the company of the woman who blew my mind on the holiday - were also deliberately placed, all parts of the 'installation'. I use the word, though in 1983 most art installations I'd seen used primal, natural materials or wall-mounted texts, and shunned quotidian, mass-produced artefacts.

Madness for me meant that sudden shafts of sunlight felt as though arc lights had been switched-on on a gigantic stage-set; rain dashing on windows seemed like basins of water chucked from rooftops by situationist agents. I'd watch the postman wheel his postal trolley up the street and admire his 'performance' and the 'well-researched accuracy' of his shabby uniform with the missing button. I'd admire the rust marks applied to drawing pins on signs in 'derelict' shop windows. Everything sprouted irony quote marks. The film The Truman Story was a fair account of this Philip K. Dick-style madness.

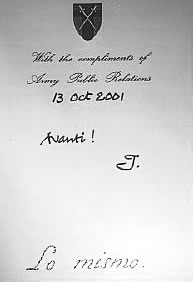

The best response to this utterly artificial universe was to begin constructing it myself. As usual for mad people, everything became a surface for signs. While typing out this text, I pulled out Truck Driver Songs from the shelf where it now rests. 'Emma I love 2 much 4 you' is written Prince-style in tiny pink capitals between the blue capitals (I was keen on Freud and Reich before I went crazy, but it still makes me blush how promiscuous was this unleashed Id). Each of the country singer's eyes has been ringed in a pink oval: though they only existed in black-and-white, their eyes were popping with neon pinks too. Behind me is a purple jacket made in Great Britain by the Avanti label: 50% acrylic, 25% wool, 20% poly-amide and 5% other fibre. Coincidentally, the comp slip placed by Prynne inside the copy of Unanswering Rational Shore contained a single word of greeting.

I did finally get my canary-yellow sock onto my foot.

I know I look like an inveterate self-publicist, but such things come with age. I've actually got very few photograps of myself in my 20s. In the punk years, photographs were almost taboo, part of the evil capitalist star-system, the spectacle. It took a veteran member of the hippie counter-culture - Caroline Coon - to document the Pistols and the Clash, and I'm not sure we've got any photographs of the countless gigs we attended and organised and fought at in Leeds. So this outbreak of narcissistic autoscopism was definitely part of my madness. It is also, interestingly enough, central to Modern Art.

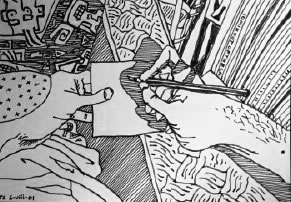

I've already argued that the optical puns of Cubism anticipate the noun/verb ambiguities in Prynne, denaturalising proof of the man-made nature of the systems we use to communicate. Autoscopism is another device which questions the metaphysical separation of subject and object assumed in bourgeois psychology. Samuel Beckett chewed on this question until he developed oroboric texts - Malone Dies (1951 (Fr), 1956 (Eng)) - in which the narrator's attempt to tell it like it really is means describing the act of writing, of moving the pen over the paper. A visual equivalent of this might be self-portraits like this.

If you take onboard the idea that the oblong being written on by the hands actually represents the whole picture, one can get slightly dizzy. The artist here has represented the blank space representing the position of the left thumb on the final drawing by marking it with small crosses.

Here the artist also had to leave a patch on the lefthand side blank where his thumb was. This process - attempting to draw actualities which a camera is too far in front of the eyeball to catch - could be taken much further, but it would require a kind of investigative modernism which the billboard spectaculism of Brit Art currently has little time for. It's interesting to attempt to draw beyond the limits of vision: diagrams of one's idea of the back of one's neck, of the view behind, or even of the motifs that float in the brain as free-floating images. Deepsea idea-fish waiting for the catch.

The poet Ian Patterson describes Prynne's poetry as 'snapshots of thought', and Prynne does seem to catch pre-conscious, interpenetrated, pre-categorical moments which mere formalist cut-up and permutation - the American tradition inaugurated by Gertrude Stein and carried on in language poetry - cannot access. Prynne goes beyond Beckett's attention to the material facts of writing to the urges and sonic mutterings of impulsive speech gestures before they've been martialled as formal grammar. In the revolutionary line that led from Surrealism to Abstract Expressionism, the automatic gesture is valued for its revelation of the unconscious. Prynne's poetry is replete with the detail of everyday life and its mass-produced trivia. However, such details are in there because they are part of the day's residues, not because they're being wielded as rhetoric in a high/low culture debate. Prynne has none of the self-conscious manufacture of a nice new 'ism' for a stable, unchallenged art market, that equivalent to a 'revolutionary new car design' from Ford Motors which made Pop Art declamatory and thin.

One of the contributors to the Mad Pride anthology is Jim MacDougall. A short, offensive story described his habit of masturbating on headstones in graveyards. It is difficult to tell whether Jim MacDougall is really mad, or merely a literary creation. He - or someone posing as Jim MacDougall - has had a presence at Mad Pride gigs. At Alternative TV's gig at the 100 Club on 2 August, he arrived, fell asleep at the front of the stage - to the fascination of various punkettes, who tweaked his hair, and one frenetic pogoer who decided to rub his naked chest - then stood up and puked three pints of lager over the stage before being helped out by Mad Pride organisers.

'MacDougall' was excluded from the launch of the Mad Pride CD at the Garage on 1 October. The venue's management did not appreciate the way he arrived, staggered around, announced he was on the guest list, and then told them he was on acid. However, although Mad Pride organisers failed to sway the iron rule of the Garage's house-manager, he did manage to slip some of his CDs past her to ATV's roadie, who put them on his stall.

The music is great, a meat'n'potatoes punk-rock chug which perfectly fits the rhythms of MacDougall's estuary English. His routines are violent, harrowing and very funny. It was also interesting to see that he put a polaroid of his own unwashed feet on the cover - a textbook case of mad autoscopism. Perhaps 'MacDougall' was proposing that we behave like Christ and humble ourselves by washing the feet of the poor. If you draw or take photographs of your own hands or feet, people often say they're 'ugly' and 'distorted' - just as some of Picasso's better paintings, where he registers the looming shapes of a lover's face and body viewed during an embrace, look 'distorted'. Actually, the perspective one has on one's own body parts is such that they will automatically looked distorted to someone used to 'objective' camera-work. We aren't living under the Pharoahs any more, however much conservatives from Plato onwards wish it were so.

Anyone who makes their own slides will immediately recognise a familiar 'problem' - those wrinkled hairy orange things on the lefthand side are my own fingers, even if they do suggest some diseased deepsea fleshcrab eyeing up MacDougall's cramped-toe anemones for sexual intercourse.

Why does Mad Pride relish the sordid and abject? Because that's how people who've been through mental illness on the NHS feel they've been treated. Yet appropriate cultural forms were needed to voice mad protest. Mad Pride couldn't exist without tapping the situationist and punk strain in British pop culture. In New York, Mad Pride takes the form of a strident identity politics. They picketed a showing of the Prinzhorn Collection on Wooster Street as an 'insult to schizophrenics', whereas Mad Pride would be far more likely to arrange a visit, lubricated by the free-beer 'medication' that seems to always accompany its events.

In Belgium, an equivalent organisation has also issued a CD:

Responding to an anti-stigma campaign launched by the World Health Organisation this year, the Belgium government declared 2001 the Year of Mental Health. This various-artist CD was issued by Het Mis Verstand in Antwerp ('non-profit organisation founded by Belgian creative minds engaged in mental health care'). 'Het Mis Verstand' is Flemish for 'The Misunderstood', which sounds pretty punk, but the contrast with Nutters With Attitude is graphic. 'Inspired by the inner world of the wrong tracked mind', both music and package - sponsored by Janssen-Cilag, KBC Bank & Verzekering and the Cera Foundation - lack the scrofulous touch of Mad Pride. The tracks on Psychoasis are light and cute, unpierced by underdog pain or protest. You're never skewered on the pin of your patronism, John Lydon-style. Both have versions of Napoleon XIV's 1966 novelty hit 'They're Coming To Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa'. On Nutters With Attitude, it's by the punk band Shockheaded Peters. On Psychoasis, it's by Rob Vanoudenhoven, a Belgian TV personality. The different versions illustrate the opposed meanings which contrasting social positions can impose on identical words: Vanoudenhoven is patronising the insane, while The Shockheaded Peters are scathing about middleclass concepts of normality. Punk gives Mad Pride a prophetic, insurrectionary glow. Iain Sinclair caught this quality when he described a list of 'sectioned carpet-chewers, white-line walkers, parrot imitators, biddable psychotics' in Lights Out For The Territory: 'folks who live with the daily horror of seeing things as they actually are' [Iain Sinclair, Lights Out For The Territory: 9 Excursions on the Secret History of London, London: Granta, 1997, p. 44].

Sinclair has been an energetic proselytiser for J.H. Prynne, writing about him in London Review of Books, and issuing Conductors of Chaos, a paperback anthology of Prynne-style extremism which rattled and disgusted the broadsheet poetry reviewers. It took a beat writer - inspired by Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, conversant with the 60s counter culture, pulp fiction and exploitation film - to see that defining Prynne as a 'Cambridge poet', a byword for elitism and excellence, is restrictive and inaccurate. In fact, Prynne's poetry evinces the same 'madness' which drives Mad Pride: a distrust for a society built on exploitation and social prestige, a suspicion that the abject and oppressed hold the answer.

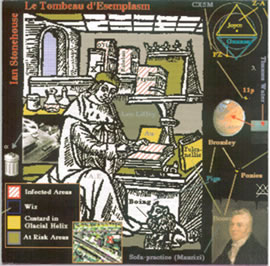

When Sinclair's characters start walking about and expressing themselves, accosting the author as they did in his latest novel Landor's Tower, threatening the publishers of the world with music demos and manuscripts, when we're freed from the curse of individual authorship, when everyone can begin talking floating-suprematist licks about breaking through the blue lampshade of the firmament, things will improve. As the dadaists said in 1918, initiating a popular catch-phrase: Jeder Mann sein eigener Fussball, or, Everyone their own Football! We meed an active reprimand to the Platonic discorporate Ideal, a sexuo-alchemical catalytic converter, a dialectical-materialist physical heave-ho with a place for madness, dreams and art arbitrariness in its all-'expending umniverse' [James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, Faber: London, 1939, p. 410, 17]. Only then, I contend, will we be able to construct the kind of collectivist, communist, esemplastic culture worthy of the gravediggers of capitalism.

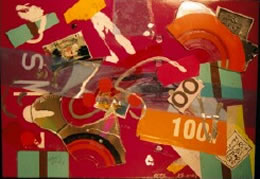

In conclusion, we - as members of the gradually expanding DIY-Esemplasm - propose a free-associative, casual and uncommodified practice which can produce "art" like this. Paul Minotto doesn't fit the class profile for an insurrectionary. He is a wealthy, post-country-soul musician who lives with his top-doctor wife in a newly-constructed palace in New Jersey. Here's a photo I took when Esther and I visited him in April.

Minotto has a Mondrian carpet, a rockery with running water in his bathroom and an artist's studio inthe basement. He drives a gold-plated Lexus, and appears to want for nothing, except maybe recognition for his loony paintings, which are a cross between Cy Twombly, Mad magazine, Cal Schenkel and Frankfurt-School-toilet grafitti. One jaded buyer refused even to look at his pictures because they contain text - 'what you mean I have to work now?' - though the way he applies and detourns his texts puts Art & Language to shame. Critic John Roberts, leafing through one of Minotto's catalogues, called it 'visual Prynne'. Minotto's mind, totally tweezed by the critico-materialist surrealism of Frank Zappa, similarly crosswires nervous energies that capitalism has forced us to channel through discreet pathways of the brain.

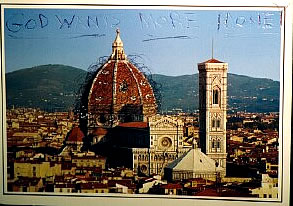

On holiday in Italy this summer, Minotto sent me a postcard whose scrawled message perfectly reflected his bourgeois stance - 'Ben, Here in Italy Tutto bene. Truly. New meaning to the word "Quality" (unlike the American version)' - but on the reverse, he'd defaced the picturesque view of Florence with angry biro.

I don't know if you can read it. His biro ink was intermittent. It says 'GOD WANTS MORE MONEY'. The celebrated florentian dome, always accompanied on TV by the pious music of Buxtehude or Monteverdi, is pullulating with greed and impatience. God and money! Are we really allowed to talk about them in the same breath today, now that "we" are at war with terrorism? This is the kind of "art" required by anti-capitalism.

More Optical Synoptix