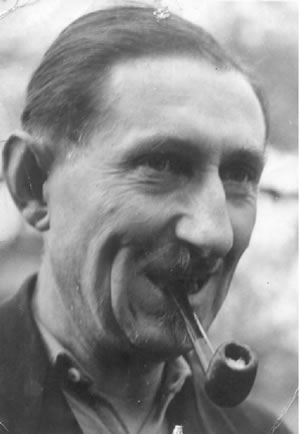

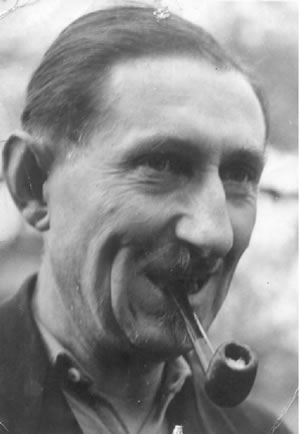

Charlie Lahr photographed by Douglas Glass

1. BEGINNINGS

At times when reading I meet my father Charles Lahr in one of his many guises. Perhaps in 1907 when together with Guy Aldred he trundles a wheelbarrow through London’s streets ‘broad and narrow’. The wheelbarrow is weighted down by a second-hand platen machine, bought for ten shillings borrowed from an acquaintance who has been convinced by Aldred of the necessity for the Bakunin press. My father is aged twenty-two, having been born in Bad Nauheim and named Carl on 27 July, 1885. He is of middle height, his brown hair stands up on his head, his nose and ears are prominent and his green eyes look out in surprise at the drab urban world through which he is passing. He has been in London for two years, but still finds difficult the transition from the villages of the Rhine to an environment in which every sign of growing life has been bulldozed.

My father struggles with the wheelbarrow, while his companion ambles along by his side, talking most of the time, expounding his ideas, waving his arms. But occasionally, when a kerb proves too high, or a hill too steep, he puts out a hand to the barrow as if to pat it on its way. (1)

I have met my father also in a greasy spoon cafe, some time after the First World War. He sits at a wooden table, surrounded by a few cronies, one with a flat, large-brimmed black hat, a second wearing a suit so shiny that it appears polished, a third wrapped about in a long, black mackintosh. They are watched over by a fat man dressed in a greasy off-white apron, who stands behind the wooden counter next to the yellow cakes and curling sandwiches. My father wears a Kaiser moustache, its ends waxed, and as he speaks its points move up and down in a kind of dance. In contrast to his companions he wears a stiff collar, tie and well pressed black suit. He is telling the story of how, before the war, he was followed for several days by two detectives who suspected him of plotting to shoot the Kaiser. This in 1907 when the Kaiser was on a State visit to Britain. A story my father is to tell many times and which is referred to briefly by William J. Fishman in EAST END JEWISH RADICALS 1875-1914.

The years pass and in 1927 we are wandering in a Rhine village. I am at home with my mother. It is August 1927 and I was born earlier in the year, on the 56th Anniversary of the Paris Commune: 18 March.

"For hours she has been struggling to escape, through the dry canal which at one moment opens before her and then closes in upon itself and her, bringing pain in its wake now that the protecting waters have drained away. In her nostrils, and unidentified by her, is the stink of blood, but she accepts it as part of what is, as she has her present journey and all that has gone before, the imprisonment, the sudden forced movements without any apparent origin, the daily changes in her physical condition - all are received by her without thought for she has no earlier experience as a source of reference. Now the canal opens once more and she responds with one final effort, launching herself forward, pushing and pulling with both hands and feet, so that at last she scrambles out of the canal and, with a cry of triumph, into the light.

My father is trudging up the hill to Hof Iben, occupied by his widowed sister-in-law, Anna. The day is cool and our companions, several young writers and an artist all of whom my father has brought from England, shiver and hunch their shoulders. H.E. Bates, Rhys Davies and the artist William Roberts are among this group and later Bates is to write a short story about the difficulties met with in obtaining a bath in these villages. Bates take careful note, for one day he will be an important writer and remark upon this journey in his autobiography The Blossoming World (pubd. Michael Joseph 1971).

The way is long and surrounded by fields of grape vines, the ripening grapes to be harvested in September. Hof Iben stands on the summit and is a building the colour of sandstone. My father stops a little way before it to tell our companions that here once stood the gates against which his brother, Fritz, bruised and bloody, his earth-stained hands covering his blonde head, was trampled by the horse and crossed by the wheels of the cart. And we see Fritz as a small boy in Bad Nauheim coming upon Elizabeth, Empress of Austria, who is living there incognito. As she walks through the village Fritz approaches her "Good morning, Your Majesty" he says politely, giving a little bow. The Empress is nonplussed. "You must not call me that!" she tells him. He stamps his foot. "Yes, I must" and holds out his hand to receive a small coin. This happening again and again.

Fritz, the brother who was said to have stolen Hof Iben from his thirteen siblings following their parents’ deaths. Buying out his brothers and sisters with money which during the inflationary period following the First World War had no value. But my father does not concern himself with this, for he is a man without desire for property or possessions.

Anna, the sister-in-law, a plain dumpy young women dressed in a dark shapeless garment and wearing her mousy hair screwed back into a bun, waits at the door. The small blonde boy Werner clinging to her skirts. Somewhere in the background is a camp in Gillingham, Dorset for Second World War German prisoners. And further away hovers the war memorial on which Werner is to execute himself by hanging. First smoking a cigar which he places on the left side of the horizontal stone cross in the cemetery.

In some confusion Anna kisses my father and glances slyly at his companions about whose crazy demands for constant hot water and regular baths she has been informed by local gossip.

Charlie Lahr photographed

by Douglas Glass

Sadly, I am unlikely to meet between the covers of books my mother, Esther Lahr, nee Argeband, known as Archer, born on 10 December 1897 at 32 Stanhope Street in the Sub-district of Regent’s Park.

"There’s a number of mentions of your father in books" says my mad cousin Cecil (whose name I mentally translate into ‘Gabriel’) "but your mother hardly gets a mention and never more than the fact that she was Charlie’s wife." "It’s because she’s a woman" I explain and Cecil is satisfied.

However, I have met my mother once during the First World War, speaking from a platform in Victoria Park in the East End, her red curly hair acting as a beacon to draw the crowds around her, to the warmth of her anger at ruling classes which send their youth to kill each other. Her bright blue eyes flash and she grasps the top of the stand which because of her small stature puts her into the position of a child peering over a wall. This glimpse of my mother was given me by Ken Weller in DON’T BE A SOLDIER published by Journeyman 1985.

Time passes and yet in itself is static. It is we who pass through time and use as signposts our inventions of seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years, so as to place our temporary existence in context and to mark our physical decay. And we invent also high days and holidays as extra markers to reassure ourselves that our journey is worthwhile. Behind us the discarded past builds up into an ever-increasing mountain of decay and this rubbish heap is known by us as history. As was first perceived by Walter Benjamin who on breaking his journey to glance behind saw clearly for the first time a wasting, withering, rotting pile. And as he stood observing, the heap spilled forward to encompass him and mark his grave. As it will for all of us.

And yet we find these signposts consoling. Therefore, I boast of my accidental connection to the Paris Commune on a day when in the Mother’s Home, 396 Commercial Road, in the District of Stepney, I am born. My tiny mother heavily pregnant is accompanied to the Home by my grandmother, Rachel Argeband (nee Wanderman), through the East End streets, past the terraces of one-storey houses whose front doors open directly onto a room; through the grey, deserted streets and the market place, empty except for a few forgotten cabbage leaves and specky apples left to rot in the gutter, across the Commercial Road where my grandmother is to be killed by a lorry in 1938 while returning home from the synagogue. But on this day she looks away, intent upon the coming birth and refuses to see herself lying stilly in the roadway, the killer lorry now stationary, while a curious group of sightseers observe her dying body. Instead, she hurries my labouring mother onwards, my mother, with pride, carrying all before her.

Rachel Argeband

Elsewhere, and far away, in Shanghai, Execution squads stalk through the town, for 1927 is the year of the Chinese Civil War, or as Harold Isaac’s calls it THE TRAGEDY OF THE CHINESE REVOLUTION and so, during the month of my birth, the newspapers exhibit pages of photographs of events ‘as they unfolded’. 2,000 British troops sent out to Shanghai to defend British financial interests, while the terror rages, let loose by the garrison commander General Li-Pao-Chang, the police of the International Settlement and the French concession. The Executioner himself bears a broad-sword and is surrounded by soldiers. Those who are wise run for cover, but not all are so quick, especially at the beginning before it is understood that such things can happen. The squad watches sharply for those distributing or holding up a leaflet to read, or to identify a striker or student, whereupon such a one is seized and marched to a street corner. Forced to bend over by soldiers he is neatly decapitated by the Executioner who has raised the sword high to bring it down to slice through the exposed neck of the victim. Then, triumphantly, the head, caught up with its expression in death of terror, or disbelief, is placed upon a sharp pointed bamboo and paraded to the next scene of execution. There are rumours in Shanghai that the terror will soon end for General Chiang Kai-Shek of the Nationalist armies, supported by the Communist Party, is no more than twenty-five miles away. But cunningly, he does not come. He waits until General Li has destroyed all left-wing political opposition, trade unionists, socialists and communists.

Then, when I am eight days old and lying peacefully asleep, Chiang enters the town to proclaim victory. Chiang rewarding Li by making him Commander of the 8th Division of the Nationalist Army.

In the meantime, my mother lies on a hard labour bed, oblivious to the noise around her of the clatter and bangs of hospital procedure and the screams and groans of fellow inmates. She is there by courtesy of donations collected by appeals for finances in the national press and from wealthy benefactors intent upon absolution with the added advantage of tax relief. It is in this manner that the working population is reduced to beggary. However, largesse stopping short of all but the plainest of fare, the lockshen soup, gefullter fish and latkas are provided by my grandmother Rachel, who makes a daily pilgrimage to our bedside.

Here I should record that Rupert Croft-Cooke, author of a number of books among which is The Last Spring

(pubd. by Putnam 1964) in which he writes of my father and his coterie, at the time of my birth wrote for me an eight page Natal Ode, published by E. Archer. Verses which start with the poet’s remark:

‘A child is born, unborn before’

As Archibald Y Campbell sings,

I find the lines not only poor

but little information brings,

Since even for the sake of rhymes

Kids are not born a dozen times....

And so I am born into a world of cruelty, compromise, murder, mayhem, megalomania, paranoia, politics as power, tactics as betrayal. But the dustbins of history are not yet full and may yet be emptied and scattered, for as Walter Benjamin writes, revolution interrupts and breaks up the heap, providing for human kind a new beginning.

I find it interesting that the debris of those past years before my birth stand out more sharply in my mind than the detritus collected immediately afterwards. For the latter form a disordered crazy paving of memory. For instance, I am in my father’s arms. We are in a street and it is dusk. He shows me his cut and bloody thumb, holding it up for my inspection. Then, I am lying on a hard bed in a white room. I am alone and perhaps I scream or cry out, for suddenly women dressed in white bustle towards me. They speak to one another and not to me, but I am given a wrist-watch to hold. then I again I am alone. I run my fingers over the glass on the face of the watch and the hard metallic back and throw it away across the room with as much force as I can muster. (2)

I am in a garden where there is a square of grass around which I pedal a small tricycle, concentrating furiously to complete the square, pushing down hard on each rising pedal for it is imperative that each journey be finished. Perhaps even then I suffered from compulsions.

I am in a garden and faces hang above me over a garden gate. Children older than myself. I know that they want to walk me up the road, but I am frightened that they will take me away and I will never return to my mother.

I am in a room and my baby sister is lying in a pram. I stand on tip-toes to place near to her head a sea-shell, so that she too may listen to the sound of the sea. My mother comes into the room and is angry. I am guilty. Guilt guilt, mea culpa, the predominant emotion of my childhood.

My father and I are in a park. On the ground and covering the path in front of me are brown, fallen leaves. Stiffly, I stand still. I cannot pass over them. "Come on" urges my father "they’re only dead!" I cry out in terror.

I am in a house empty of furniture. I walk up the stairs, to spy through an open door a floor fascinating in its gleaming darkness. My mother calls to me, but I run onto the floor to fall and be stained by its blackness. Of course, it is no accident that I remember this fall onto the darkened floor at 9 Wilton Road - the domicile of my childhood - for its black stain which then covered my hands, limbs and dress, subsequently, under the tutelage of the nuns, penetrated into my soul which throughout my childhood I see as a black sole-shaped image occupying my body.

However, these are my earliest memories and I have held on to them for more than half of a century, although I must have forgotten events of much greater moment. Perhaps these recordings have persisted because they form the very basis of my memory and so take up what space they please. It is the memories which follow that have been forced to fit in where they can and have become increasingly compacted over the years.

The house at 9 Wilton Road is detached and the first house to be built in that road. It was built and occupied by a Master Builder, W. Piddington Esq., who had also badly designed it. He lived there, until his death , with two spinster daughters who waited upon his every want, but as soon as they were free, happily they sold up and fled. In later years the builder had become blind and so when we moved into the house the garden was a jungle. Of course, at times the blind Builder had forgotten that the neatly laid out lawn, the carefully cultivated shrubs and the straight rows of border plants were overcome and lost beneath bramble, bracken, waist-high grass, tangled weeds and self-seeded trees, for in his mind’s eye he saw still his neat suburban paradise. Then, he would step out into its rank disorder, stumbling and cursing and hitting out with his white stick at the vegetation which he could feel, but not see. His two daughters shrieking at him from the doorway "be careful! Be careful!"

My father soon tamed the savage growth and planted rows of cabbages, potatoes, tomatoes, beans, peas, fruit bushes and trees, and other edibles for having come from peasant stock he saw this as the appropriate use for a piece of ground. However, my mother led him to compromise by introducing borders of flowers and allowing my sister and me a very small piece of grass on which to play, although it was never adequate and I longed for a lawn large enough for me to practice the long-jump, at which I rather fancied my chances. But, for the most part, admonitions not to step on beans, potatoes, tomatoes and so on interrupt my childhood.

Now, many years later, the wilderness has reclaimed that garden and once again the blind man stumbles through its maze thrashing about him with his white stick, but his daughters no longer call to him, while the shade of my father grits his teeth at such waste of land.

When she first moves into 9 Wilton Road, Muswell Hill, London, N10 my mother is happy for she has arrived at an important milestone on her way up the heap. An indicator which shows her and my father as the proud possessors of a mortgage for a 3-bedroomed house, all mod cons, in a delectable suburb. Certainly a progression from whence she had come - the East End with its crowded tenements and its concreted-over fields and verdure.

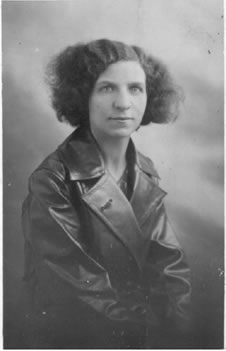

Esther Lahr, 1920s

My mother’s life had begun long, long ago, before she was born, when the persecuted Jews fled from Russia and Poland in response to edicts, pogroms and expulsions which made them set sail in whatever craft was available. Sometimes a scene in my mind’s eye shows me people waiting patiently on a dock, watching the black, uninviting water and tossing ships. The men dressed in broad-brimmed black hats and the women in shawls which cover their bewigged heads. Their faces are pale and they clutch at each other for support. The children, their eyes big and round, hang on to their mother’s skirts.

But perhaps, because human beings are so resilient, the picture should be one of bustling activity, shouting and arguing, persons with waving arms running back and forth yelling instructions and admonitions at one another and at playing children who chase each other and ignore their parents’ commands. However, whatever it was like, my mother was born out of this turmoil to be a first generation Englishwoman.

It must be remembered that early immigrants from Eastern Europe, heirs to the Anarcho-Communist tradition, fought for an improving quality of life. Fought against the sweater, the slum landlord and against discrimination. Throwing off also the restrictions of a culture brought from a foreign land. And for my mother, this culminated in a detached three-bedroomed house in Muswell Hill which, on her part, was a compromise for in the absence of the overthrow of existing society and the building of the new, she must accept a substitute and settle for what was, ‘bettering herself’ in the only recognised manner.

But this did not prevent her in later years, when she no longer worked in the bookshop which was hers, but which had become my father’s, from lamenting her isolation in this dull, conventional suburb. By then she was marooned, largely by poverty, at the edge of which we coped for the next few years because by the end of 1929, in common with business generally, the book trade slumped. Later, it might have recovered, but in my father’s unbusinesslike hands this became more and more unlikely.

When my mother was overcome by the pain of living she screamed against the four walls between which she was trapped and her voice bounded off each wall and hit us, her children, buffeting us into corners, driving us from room to room. My father is never there to be caught in her desperate anger for he is a man who comes home for an evening meal only and to sleep.

Sometimes my mother, as if in memory of the former occupant, the Builder, blindfolds herself with a dark band as the only way to escape; protesting all the while that she is only resting her eyes. I sit on the edge of a chair, watching and listening to her, the tears running down my face, for I am convinced that this temporary blindness is permanent and that her maiming is mine also. I weep and wail and my mother becomes angry and declares that she wants to die. At this I shake with fright and terrified that I will lose her, I invent a headache or stomach-ache so that I do not go to school. Then, all day long I watch over her waiting for her mood to lighten and for us to be once again happy.

But those are the bad times and when we first move into 9 Wilton Road its sunless rooms are filled by a rosy glow and the house itself is enclosed in a rainbow. But is only a month later, in October 1929, that the recession whirls like a tornado around the globe, whipping up and obliterating numerous small and large businesses and investors. There had been a harbinger in the previous year when in May 1928 panic selling had hit Wall Street, but this had been regarded as no more than a hiccup. Other harbingers during that year bore no direct reference to the coming slump, but they joined the heap of history and bided their time, for events have a habit of forming themselves into a pattern, into a gestalt.

In China, where confusion had so marked the year of my birth, the Kuomintang has murdered at least 140,000 dissidents during a terror which laid waste the countryside.

In the USSR in January 1928 Stalin exiled all key opposition figures. Leon Trotsky exiled to Alma-Ata on the Russian Chinese frontier.

On 27 August Britain signs a Treaty renouncing war to which representatives of fifteen countries meeting in the French Foreign Ministry append their signatures. Amidst cheers, the first to sign, is Gustav Stresemann, the German foreign Minister.

Almost a year later, on 9 June, two days after my sister’s birth in 1929, it is decided, under a plan named for an American Banker, Owen Young, that the German reparations debt for the First World War, paid to the allies and chiefly to America, will not be cleared until 1988. The Stalheim (soldiers’ private army) hold demonstrations to pressurise the Reichstag against this plan.

Perhaps, even then, the figure of my father hovered at Potters Bar, some time in the years 1936-38, holding the hands of two small girls. We are standing at the edge of a large crowd of German veterans from World War I, veterans now living in the UK. From somewhere above us comes the voice of the speaker at this Remembrance Ceremony, the Nazi Herr Von Ribbentrop, German Ambassador to England. "Für die, die für’s Vaterland gefallen sind" he thunders (for those who have fallen for the Fatherland) "und for die, die Sie ermordet haben!" shouts back my brave father (and for those you have murdered!) Hiding in the shadows are the death and destruction of the Second World War, the Holocaust and the threat of nuclear annihilation.

Of course, the recession of 1929 announced by panic and riot on Wall Street, police dispersing hysterical investors, should not have taken my mother by surprise, for had she not made an assiduous study of Marxist economics? Was she not fully conversant with its theory of capitalism’s cycles, culminating every few years in commercial crisis? Or did she, as an ex-pupil of a Board school, where learning by rote was the order of the day, see Marxism as merely another lesson which remained firmly between the covers of a text-book? Or did she hope, as we all do, that disaster is something that happens to other people?

My mother found her changed circumstances especially galling, because when she had first moved into 9 Wilton Road, she had boasted to her family of the bookshop’s success. My grandmother, my mother’s available siblings and various other members of the extended family, had been invited to view and praise this suburban house. "Look at me!" my mother’s deportment said "I am not the shlemiel you thought! In spite of what you call my mad socialist ideas and a gentile husband! I’ve got a pretty little house and two well-kept children, even if they are only girls."

There is no record of what my grandmother Rachel said, but she arrived at this non-kosher household carrying her own food and her own pots and pans, the latter tied together on a string and slung about her neck. As for my Aunt Becky, she was peeved, yet proud, of these symbols of her sister’s success, but she murmured to her husband and to other family members "We know they’re both meshigeneh, so let’s hope they can pay for all this!".

And yet, and yet, and yet. Perhaps even then in those tidy rooms with their bookshelves and prints upon the walls, could be spied the ghosts of our future tenants who for some years rented the three upstairs rooms, while my parents, sister and I crowd into the rest of the house.

However, at the time of the first visit to the house, my mother must have regretted that her father had died on 30 January, 1926 and so never saw the house, nor her children, for of all her family he was the person she most wanted to please and impress. It was my grandfather, Samuel Argeband, whom I never knew, who inculcated in my mother a love of learning. Whereas my grandmother was not literate, my grandfather had been educated in his native Poland, both at school and, as a male, at the Shul. Therefore, he was able to translate this knowledge into learning to speak, read and write good English, and so help his children with their school work. Esther, as the youngest, coming in for much of his attention:

Esther as teenager

In those days, Esther flew on winged feet along the streets of the seaside town, the smell of ozone in her dainty nostrils. At about the same time and at another place, my father-to-be Carl, sniffs also at the sea as he leans over the side of a ship bringing him to England. No passport, no papers, for as he was in the future to say often ‘two world wars for freedom and freedom lost!’ But, my mother-to-be skims over the pavements oblivious of Carl’s ship tossing on the water, passing sailors sipping their pints outside street corner pubs and doing her best to avoid knocking into women carrying shopping baskets, some of whom pause for a moment to wonder why a small ginger-haired girl is running like the clappers.

"Dad" she shouts, running through the open front door of the Portsmouth house. The father, a thickset man of medium height whose drooping moustache gives his face a melancholy aspect, rises from his chair with an effort. "What now!" he mutters, but puts on his father face for his pretty, bright, youngest child as Esther opens the living-room door. The Father has been sitting all morning in a large, shabby armchair, drawing life into his lungs, while his wife works at their market stall, for he is struggling with asthma, bronchitis and emphysema. Since moving away from London smogs and giving up barbering (on my mother’s birth certificate his occupation is given as ‘Master Hairdresser’) his health has improved, but he continues to suffer occasional attacks. Now he stoops forward to catch his breath. "Stop, Esther" he wheezes, "don’t be so noisy". She stands still, her eyes wide. "Dad", she says earnestly, "my teacher says we’re to find out the countries of the British Empire. All of them. She’s going to ask us this afternoon, can we look in the book?" ‘The Book’ is an old encyclopaedia picked up from a junk stall. The Father smiles proudly at this daughter who thirsts so for knowledge, and takes down a thick tome from a shelf built into a recess. Then, gladly he sits down again, Esther beside him on the arm of the chair. They turn the pages, Aa, Ab and so on to the Ba, Be....at last Br, British, British Empire. The Father shows Esther a map of the world - green, yellow, mauve, orange, but mostly pink. "all the pink countries are the British Empire" he tells Esther and they both marvel. Esther seeing them all covered in pink grass, pink skies, pink trees, pink houses... India (the Jewel in the Crown) British West Africa, British Central Africa, British South Africa, Ceylon, British West Indies, British East Indies, British Guiana, Gibraltar, Malta, Falkland Islands, British New Guinea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Sudan, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland...

Truly, this is magnificent, for here they are, a formerly subject people, dispossessed, driven out of lands where they had been ghettoized, restricted, enacted against and murdered. And now, not only are they free, but they are the heirs to an Empire on which the sun never sets!

Esther finds paper and pencil and quickly copies out from the encyclopaedia her new-found knowledge, certain of returning to school triumphant.

This is the same man who is to say to my mother three or four years before my birth "you’ll never have children, it takes guts to bring up a family." That is why I owe my being directly, as well as indirectly, to my grandfather, for my mother, anxious to prove herself to him, decides to become pregnant. This was with ‘Poppy’ who was to be stillborn on, or about, 11 November, some two years before my birth. 11 November, Armistice Day, on the eve of which in 1938 my grandmother Rachel is to die. ‘Poppy’, a pale child with dark hair and bright blue eyes. My mother’s stories bring Poppy back to life and for years my sister and I play that we have an older sister and include her in our games. Now, my mother desperate to produce a live child, embarks upon a further pregnancy, but by the time I am born my grandfather, Samuel Argeband, is dead, at the age of fifty-six years, in the East End of London. His occupation once more barbering, his heart worn out by the constant struggle to breathe and the complications which followed.

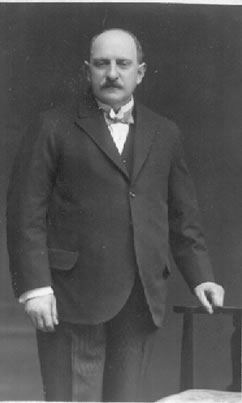

Samuel Argeband

My mother once told me that she wanted neither of her children to grieve for her in the desperate way she mourned her father. But this was not within her gift.

The father is lying in the high double bed, its brass bedstead dull in the half-light, for the curtains are drawn although it is day. He is propped up high on pillows and his chest rises and falls with his effort to breathe, each rasping breath cutting through the silence of the room. His daughter Becky, a plump young woman whose skin hangs on her heavily, is there to watch over him while her mother is at the market. Restlessly she is thinking about all she has to do at home and awaits impatiently her mother’s return. "Florrie’s frock is only half-sewn, the sleeves to be put in I’ll do it this evening blue should be a good colour for her not too light to get dirty quick Woolfie’s gone through his socks again get some at the market when the Mother comes home soon I hope or Esther looks in about time she looked in". She gets up and twitches the curtain back to look out into the street for a moment, then shrugs and sits down again, glancing across at the Father as she does so.

"Always sick Mother’s had a hard life we’ve all had to take on his burdens nice to be ill could I be ill with Gussie and the children at my back all day and night? now I’m expecting again the powder didn’t do any good just as well Gussie would have been suspicious all right for the men they don’t have to bear ‘em or care for ‘em I was really sick this morning really heaved could I sit down let alone lie in bed? no it’s Mum this Mum that Becky Becky Becky what did Sam say Becky at beck and call well he was right he was a nice boy married that Bloomfield girl not good looking and running to fat what’ll I give Gussie for dinner tonight the children can have bread and jam they had fish at dinner they ate well that Esther’s a smart one all right no babies lives like a lady."

The Father coughs and she looks towards him. "He gave her one hundred pounds to start that shop a hundred pounds all that money they’ll never get it back what’s she ever done for him and it’s me who’s given them grandchildren hers was born dead and who knows the reason for that and they’ll never be brought up Jewish not proper grandchildren they’ve only got me but they can’t see it Esther’s too busy acting the grand lady in that dusty bookshop with her goy friends and Charlie lit-er-ary they call it I call it littery (she smiles to herself) Woolf was educated calls himself Wilfred disappeared somewhere in America no one knows where Mark’s a shlemiel now his boxing’s over never fight again he needs a woman behind him one who’s got her head screwed on right too fond of shiksas never do him any good took his money Esther was spoilt since she was little I won’t make more of one than the other ‘tho Gussie makes a fuss of Florrie I hope that’s not an unlucky name terrible for poor Flora dying like that by fire and the children they take me for granted."

The Father coughs again and Becky gets up from the chair and goes to him. "How are you Dad?" He closes his eyes without answering. "Don’t tell me then!" Resentment bubbles up inside her and explodes in bitter words. "You want to pull yourself together!" His eyes remain closed and he gives no indication that he has heard her. Maddened by what she sees as his indifference she finds words shouted at the Father by the Mother over the years when little money was coming into the house and there were hungry mouths to feed and bills to pay. "You’re lazy!" she taunts the dying man, leaning over him, this man who has controlled her during her growing years and is now within her power. "You’re lazy - even Esther says you’re lazy!"

Esther, who in the light of her Father’s illness has decided not to go to the shop, catches these last words as she opens the bedroom door and for a moment it is as if she has been hit by a physical force which knocks all the breath from out of her body. She stands in the doorway unable to move. Becky, at her sister’s entrance, has turned away in confusion, but decides to brazen it out. "Oh, you’ve come then at last!" she hectors. "Not before time!" Esther ignores her and goes to the Father, taking one of his unresisting hands into her own. He turns his head, opening his eyes to look at her and within them she senses reproach. "It’s not true Dad" she half whispers " I never said that. She’s lying, her voice breaks and the Father looks away without giving any sign that he believes in her.

This scene haunts my mother to the end of her life for she had forgiven him long ago for hurts for which she had never blamed him.

Proud of her cleverness, he had promised that when the time came for her to leave the small Church School which provided an elementary education, he would pay to send her to a High School.

Esther walks happily home from school, her head in the air. Carefully folded in her coat pocket lies the certificate from school stating that she has completed successfully all standards and can leave school at the age of thirteen. "My Dad’s going to send me to High School!" she has boasted for weeks to her schoolmates and even to her teacher, Miss Turner "where I’ll wear a uniform and learn French and Latin and Grammar." This information had brought varied responses from the sneering to the envious to the well-wishers. Miss Turner had suggested "Perhaps one day you’ll be a teacher" and Esther, for a moment, had seen herself as the fount of all wisdom. Therefore, when she arrives home and hands her leaving certificate to her Father with almost a flourish, she expects him to confide in her his plans for her future. Instead, without comment he takes the piece of paper and puts it high on the shelf in the recess, next to the encyclopaedia. Then he turns away from her to sit in the armchair and bury his head in a newspaper. She hovers for a moment, wanting to ask him "When am I going to the High School?" but caution, or perhaps fear of his reply, makes her hold her tongue and for the rest of the day she holds onto her dream, making excuses to herself for her father’s silence. Later that evening her Mother calls Esther to the kitchen. "The Father says you’ve left school. Milly will call for you Monday at half-past seven." Milly is the sixteen-year-old daughter of a neighbour. Esther is confused. "With Millie to school?" "School, schmool!" scoffs her mother, "you’re too old for school. Manny Abelman says you can start at the factory for making cigarettes. It’s time you brought some money in instead of head-in-a-book!"

And so my mother becomes a cigarette-maker for some years, having first been instructed by her mother always to wear demure clothing and never to look the boss, the foreman or any other male in the factory, directly in the face, for tales of seduction, or even rape, are rife, culminating in illegitimate births and utter disgrace for the girl. With regard to education, what little money the family had was spent on Woolf, Esther’s eldest brother.

My father at this time is living with the woman who is to become known as ‘the first Mrs. Lahr’ and who figures as a harridan in one or two short stories by my father’s writer friends, much to my mother’s chagrin as she feels that she herself will be mistaken for this character. I know little about this woman except that she ran a lodging house into which my father introduced his Anarchist and socialist friends, most of whom were unemployed and down-and-out. Every morning my father awakens them by singing the first two lines of The Internationale:

Arise ye starvelings from your slumbers

Arise ye criminals of want.........

a practice he is to continue with us throughout our childhood and always badly out of tune, for he is tone deaf.

For my mother, at the age of thirteen, the routine of the factory dulls her spirit, but does not kill it for when her friend Sadie, a tall, buxom, dark-haired girl, in every way a contrast to Esther, says to her "Let’s go to Manchester and try for an audition with Hayley’s Juveniles" Esther is enthusiastic, for all her life she is to love music and move like a dancer. Maybe they’ll tell her that she is too short, that her bottom is too near the ground, the words of a Foreman at the factory, but it is well worth a try. Her blue eyes blaze with determination.

In the early hours of the morning, Esther, clutching a paper bag creeps quietly out of the bed which she shares with Becky, and makes her entrance onto the stairs. Becky, whom she had thought to be asleep, unknown to Esther, sits up on her sister’s exit and gets out of bed to wait off-stage behind the door while the drama, or farce, is played out. Esther places her feet carefully on each step as if they are leading her into a dance, a simple routine to end in the hallway in a complicated manoevre, legs flung into the air, a twist and a twirl, arms flying, head nodding. At last she is in reach of her goal, the front door and freedom, soon to open on a new life which will lead to fame and fortune. Nearly there! As she puts out her hand to unfasten the lock she hears a sharp step behind her and before she can turn a rough hand grabs her shoulder: "Where do you think you’re going!" She has never heard her father so angry. "A bad girl you are, want to bring shame on the family, want to be a painted harlot, never come in this house again!" He gives Esther no opportunity to answer, but propels her into the living-room. "Sit!" he commands "and wait until it’s time to go to the factory. I take you there myself."

Later, Esther is to hear that the same scene has been enacted in Sadie’s house, for Sadie’s older sister has discovered the plan, revealed it to her friend Becky, and both of them have informed their parents. Much later, when Gracie Fields becomes famous and it is known that she began her career with Hayley’s Juveniles, my mother feels doubly deprived. Never watching or listening to Gracie without seeing herself somewhere in the background.

In those days, Becky always seems to be the cause of my mother’s downfall. A few years later, my mother remaining intent upon changing her life-style, and interested in the suffragette movement, makes a stand for women’s freedom by having her hair bobbed. Her hair is only shoulder length for curly hair never grows too long, but Esther is expected to put it up as best she can and, according to conventional fashion, secure it tightly in hairpins. What nuisance in this procedure every morning and her head always feels as if her hair is being pulled out by the roots. At last the offending hair lies on the floor around the barber’s chair, brightening the dull lino, but she feels no regrets, only a sense of liberty as she tosses her head without feeling the pulling of pins against her scalp. She walks, hat in hand, down the Charing Cross Road, turns into Leicester Square, along Coventry Street, to find herself in Piccadilly Circus. The centre of the British Empire! This is surely an appropriate place to strike a blow for women’s freedom! She takes a cigarette and a box of matches from the pocket of her long black coat, and lights up. What bliss! She, a woman, daring to smoke in public! One or two passers-by glance at her curiously, and a foxy looking man in a shabby coat and brown hat tries to pick her up, coming alongside to say "Hello, girlie. I’ll see you home". But she doesn’t answer and quickens her pace, so shrugging he goes on his way. soon Esther decides it is time to go home to the East End and familiar streets, but as the tram nears her stop her courage fails and she jams her hat firmly onto her head before alighting. On arriving home Esther finds her mother in the kitchen while her father sits in his usual armchair and Becky is at the living-room table fitting together pieces of a dress ready for sewing. Becky glances up as Esther, still wearing her hat, passes by and then suddenly, with one movement, Becky pulls the hat from off her sister’s head. "Look! Look!" she shrieks "she’s had her hair bobbed!"

And yet it was this same Becky, who, together with the Mother, tended Esther day and night when she was near death with the influenza which swept through Europe and the British Isles at the close of the First World War. This epidemic doubling the war casualties.

No, it was no problem for my mother to forgive her father for unimagined wrongs, it was herself she could not forgive. For she saw herself as a collaborator in her father’s early death. This, because when Rachel, after the death of her eldest daughter Flora and two of the grandchildren in the fire, asked Esther and her siblings "Do you want to go back to London?" None of them understood that this would be a life and death decision for their father, for there he would not only once more breathe in City smog, he would return to line his lungs with hair from barbering. "London!" Esther and her siblings shouted "Let’s go to London!"

But it was London which gave me life, for my parents met in the Charlotte Street Socialist Club after the First World War, when my father had been released from internment from Alexandra Palace. It should be put on record that my parents were introduced by young Rocker, the son of Rudolph Rocker, appearing in books by William Fishman and spoken about by him on the radio.

Internees at Alexandra Palace

during the First World War - Charlie Lahr sits in the front row, 3 from left

On to New Coteries